On March 5 2021, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA, 2021) and the ICE Benchmarking Administration (IBA, 2021) officially announced the definite end dates of the LIBOR (London Interbank Offer Rate). According to these announcements, the publication of all euro and Swiss franc, most sterling and Japanese yen as well as the one-week and two-month US dollar-LIBORs will be ceased immediately after December 31 2021.

For the remaining US dollar-LIBORs it is currently intended to extend publication until June 30 2023, whereas for Japanese yen and sterling the remaining rates will be published on a synthetic basis after the end of 2021 for one additional year.

The announcement of the FCA and the IBA marks another milestone in the replacement process of LIBORs with risk-free rates (RFRs), e.g. the Sterling Overnight Index Average (SONIA) for sterling-LIBOR or the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) for the US dollar-LIBOR.

This replacement process can be traced back to a report published by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in July 2014, in which the FSB spots light on various drawbacks of LIBORs and calls for the implementation of robust reference rates in order to replace LIBORs (FSB, 2014).

However, with about $400 trillion value of financial contracts referencing to the LIBOR in one major currency in mid-2018, the LIBOR is often regarded as one of the pillars in modern finance, resulting in considerable challenges in the transition away to RFRs (Schrimpf & Sushko, 2019).

This is further complicated by the fact that substantial differences between LIBORs and RFRs have to be taken into account, which makes a simple replacement often difficult. Against this background, market regulators, financial authorities as well as various working groups are regularly providing updates on the latest developments on the transition process and offer recommendations in order to enable a smooth replacement of LIBOR.

The discontinuance of the LIBOR has also a considerable transfer pricing (TP) impact for multinational enterprises (MNEs), as LIBORs are often used in inter-company (IC) cross-border financial transactions, e.g. loans, deposits or cash pooling transactions. If, for example, an IC agreement does not contain a fallback provision, which specifies the adjustments necessary to transition away from LIBOR, tax authorities might argue that the adjustment of the reference rate constitutes a significant modification of a contract.

In this case, other relevant terms and conditions of the IC agreement would also have to be renegotiated (Ledure et al., 2019). In addition, taxpayers have to ensure that the transition away from LIBOR is in accordance with the arm’s length principle and does not lead to a cross-border value transfer between related entities. Taking these aspects into account, there are major challenges for legacy IC transactions.

In this article, recent developments on the transition away from LIBOR are analysed and discussed from a TP perspective. In particular, potential successor rates for the replacement of LIBORs in IC financial transactions are first introduced and compared.

Based on this analysis, practical implications from a TP perspective are presented. The article ends with an overview of various aspects that MNEs should keep in mind in order to enable a smooth transition away from LIBOR.

Differences between LIBORs and RFRs and potential successor rates

Because of several problems associated with LIBORs that the introduction of RFRs is intended to address, there are key differences between LIBORs and RFRs that taxpayers should be aware of.

One crucial distinction is a term credit risk spread ( Working Group, 2020a). This spread results from the fact that LIBORs are solely based on interbank transactions, whereas the underlying volume for RFRs is not restricted to interbank markets. Instead, RFRs also consider non-bank counterparty transactions and are thus rooted in much larger markets. For example, SOFR is based on close to $1 trillion, whereas estimates for the US dollar-LIBOR show that the volume of three-month wholesale funding transactions by major global banks on a typical trading day is merely $500 million (Federal Reserve, 2018).

The reliance on actual transactions as well as much larger transaction volumes should make RFRs less susceptible to market manipulations, which is one of the major problems of the LIBOR that may date back as far as into the early 1990s.

Another specific feature of RFRs is that they are published as overnight rates. In contrast, LIBORs are available for different maturities of up to 12 months and are known at the beginning of an interest period.

Based on the overnight character of RFRs, various adjustments have been proposed to enable a smooth transition away from LIBORs with different maturities. The most frequently mentioned modifications are so called term RFRs that can be separated into two different categories (ARRC, 2021).

Within the first category, term RFRs are constructed from past realisations of overnight RFRs (backward looking approach). In this case, the interest payments over a period of, e.g. three months would result from the average overnight interest rates of RFRs over the same term. The construction of term RFRs could either be based on the simple or a compound average of overnight rates.

In addition, the average could reference to a period before the current interest period begins (in advance) or to the current interest period (in arrears). In the first case, term RFRs would be based on observations of overnight RFRs before the interest period begins and would thus be known in advance. In contrast, for an in arrears structure the term RFR would be based on the overnight rates during the interest period and would therefore only be known at the end of the period.

The second category of potential replacement rates for the LIBOR with different maturities are so called forward-looking term rates (FLTR), that are derived from executable quotes for RFR interest rate swaps (forward-looking approach) (FFIC, 2021). Like LIBORs, FLTRs are fixed at the beginning of a term period and are thus known in advance as they are not based on past realisations of overnight RFRs.

In addition to the determination of RFRs with different maturities, further economic differences between LIBORs and RFRs must be considered. For example, the absence of a term credit risk spread should be taken into account in order to avoid a value transfer between borrowers and lenders, as it is generally not expected of market participants to give up on the spread between LIBORs and RFRs. Therefore, an additional credit adjustment spread should be added to the term RFR to mitigate a value transfer. This spread could either be based on the historical (five-year median) difference between the LIBOR and the RFRs or on the forward-looking basis SWAP market (forward approach).

Apart from term RFRs, another option for taxpayers might be the replacement of LIBORs either with specific base rates (e.g. bank prime lending rates) or with fixed interest rates (Working Group, 2021).

With respect to the euro, it should be noted, that in contrast to the LIBOR, the EURIBOR was reformed in 2019 and will continue to be published after 2021 (European Money Markets Institute, 2019). Market participants are thus not obligated to transfer to the euro short-term rate (€STR) as an alternative RFR. It should be kept in mind, however, that the robustness of the EURIBOR is not guaranteed in the years to follow and thus market participants should generally consider adequate fallback rates in their IC agreements.

Based on the different alternatives that could be used in order to replace LIBORs in IC financial agreements, forward and backward-looking term rates for the SONIA are first compared with each other as these rates are generally regarded as the main potential replacements. Afterwards, recommendations for the transition away from LIBOR are discussed and implications from a TP perspective are derived.

Comparison of forward and backward-looking SONIA

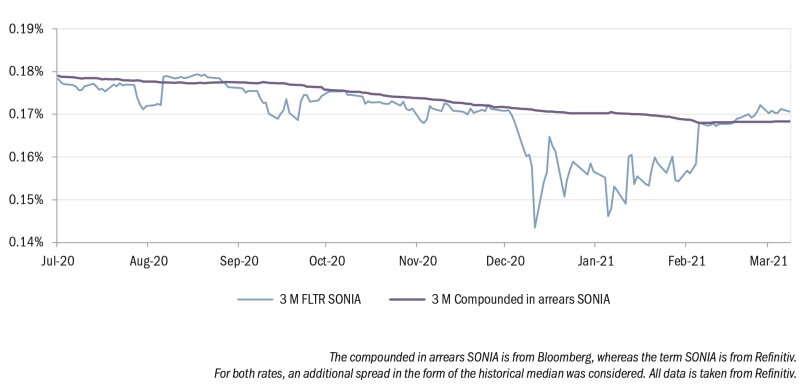

The figure shows the time series for the three-month compounded in arrears SONIA and the three-month FLTR SONIA from July 2020 to March 2021. In general, both rates show a negative trend till February 2021 and are relatively stable afterwards. At the same time, the FLTR exhibits a much higher volatility than its compounded in arrears counterpart, especially after the end of 2020.

As backward-looking rates are based on the average of past observations of overnight RFRs, one major advantage is that they are less affected by sudden short-term market fluctuations as well as quarter- or year-end adjustments. At the same time however, backward looking rates tend to lag behind recent market movements and do not contain the latest expectations of market participants.

In contrast, FLTRs consider the most recent market developments and reflect the market participants’ expectations about future market conditions. However, supervisory authorities have already expressed a number of concerns about FLTRs (FFIC, 2021).

In particular, the robustness of these rates heavily depends on the liquidity of the underlying swap markets, which may vary considerably according to market conditions. In addition, the use of FLTRs might lead to a detraction from products referencing to backward looking rates. However, as these rates are indirectly used for the FLTRs, this could lead to a deterioration of their underlying basis.

Figure 1

General recommendations

Financial authorities, market regulators as well as various working groups consisting of private and public sector groups have provided recommendations in order to allow a smooth transition away from LIBOR. However, these recommendations are generally not binding and tax-payers must decide individually whether and to what extend they will rely on them as they generally only ought to be understood as a starting point for a successful transition.

As the EURIBOR will still be published after 2021, the following recommendations primarily refer to the two major LIBOR currencies: sterling and US dollars. However, as it is generally understood that the transition should be as uniform as possible across all LIBORs, these recommendations can be at least partially applied to other currency areas as well.

Based on the various advantages and disadvantageous of backward and forward-looking term rates, the Working Group on Sterling Risk-Free Reference Rates (Working Group) as well as the FCA have stated that the compounded in arrears rate should be the backbone for the transition away from sterling-LIBOR to SONIA (Working Group, 2020b). According to the Working Group, the compounded in arrears SONIA should be an appropriate replacement rate for most financial products (i.e. for c. 90% of loans by value).

Similar, the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC), which is a group of private-market participants convened by the Federal Reserve Board and the New York Fed, also recommends a backward-looking term SOFR in order to transition away from US dollar-LIBOR. However, the ARRC expects that in most cases the in advance structure would be the more appropriate method instead of the in arrears.

With respect to the construction of the average SOFR, the ARRC points out that the simple average has a long-standing convention and is probably easier to handle for most operating systems, whereas the compounded average accurately reflects the time value of money. Taking these aspects into account, the ARRC recognises that either convention could be used and that the choice should depend on the specifics of the product (ARRC, 2021).

Irrespective of the specific structure of the backward-looking term rates, the ARRC explicitly states that market participants should not wait for the construction of FLTRs. Additionally, the ARRC points out that the use of a forward-looking term rate might lead to an increase in transaction costs in comparison to an average SOFR, which would raise the hurdles for using FLTRs.

With respect to the potential use of bank prime lending rates, it is also acknowledged that in some cases counterparties may be more comfortable to transition to bank prime rates as they have a better understanding of them.

TP implications

From a TP perspective, neither the OECD nor the recently released Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing from the UN contain any recommendations on a transition away from LIBOR.

Based on these aspects, the transition from LIBOR to RFRs should be at arm’s-length, meaning that the transition should mirror the conditions that could also be found between independent parties.

As it can be expected, that for most financial transactions, independent parties will use backward-looking RFRs as a replacement for the LIBOR, taxpayers should consider this as one of the first options.

Only in specific cases, in which the taxpayer can explicitly justify the rationale behind a deviation, the outlined alternatives could be considered. One potential rational would be the requirement of absolute certainty on future cash flows that are based on recent market expectations. In these cases, a term rate might be the better option. According to the OECD Chapter X Sections 10.76 and 10.94f, taxpayers might also consider the external refinancing conditions of the MNE group as a point of reference.

Irrespective of whether a backward or a forward-looking term rate are used, a spread adjustment might be included to avoid value transfers between cross-border borrowers and lenders. Additionally, the term of the RFR should be the same as for the LIBOR, i.e. if the LIBOR has a term of three months, the term of the RFR should also be three months.

Another potential advantage of backward-looking term RFRs is that these rates will probably also become the norm for most derivatives, bonds, as well as bilateral and syndicated loans. Taking this aspect into account, the verification of the arm’s-length character of IC financial transactions, which is often based on bond transactions, would be simplified.

Even though the consideration of fixed or prime rates is generally regarded as an option, taxpayers should keep in mind that this might lead to an interest rate risk transfer between lenders and borrowers.

In addition to the specific points outlined above, taxpayers should try to use the same mechanism for similar transactions to ensure a consistent behaviour. Furthermore, the transition should be documented, including but not limited to the underlying method applied for deriving the RFR and the options realistically available.

Summary and further aspects

Based on the definite end of the LIBOR, taxpayers from MNEs should be aware of the potential challenges and counter measures that could be undertaken in order to allow a smooth transition away from LIBOR. In particular, the following aspects should be considered:

All new IC financial transactions should no longer be based on LIBOR.

If however, any new IC financial agreements are still referencing to LIBOR they should contain clear contractual agreements on how to switch to RFRs or other alternative rates.

Taxpayers should review all existing IC financial contracts that go beyond the end of 2021 and should start to transition away from LIBOR. In doing so, they should not wait until LIBORs are no longer published and instead actively seek a transition process.

It is generally expected that a backward-looking term rate might in most cases be an appropriate replacement for LIBORs; and

Finally, taxpayers should try to harmonise the transition process across similar IC financial products and should document the transition accordingly.

Ronny John |

|

|---|---|

|

Director Deloitte Germany T: +49 34 1992 70663 Ronny John is a TP director at Deloitte Germany with more than 15 years of experience. He is head of Deloitte TP real estate EMEA. Ronny specialises mainly on inter-company financial transactions, financial services, and real estate industry. He supported multinational clients in structuring, reviewing, and defending their treasury function (IC loans, guarantees and cash pools) in tax audits and dispute resolutions (MAP/APA) during his prior tenure in New York and Frankfurt. In doing so, he places particular emphasis on offering understandable and pragmatic solutions that meet the client’s individual requirements. Ronny regularly publishes in key tax journals on recent TP topics and is a frequent speaker at TP events. He is a certified German tax advisor and holds several university degrees in economics, business administration (corporate and investment banking) and accounting and taxation. |

Christoph Mölleken |

|

|---|---|

|

Consultant Deloitte Germany T: +49 34 1992 7034 Christoph Mölleken is a TP consultant at Deloitte Germany. Christoph has more than seven years of experience in the area of financial markets as well as banking and holds a doctorate in economics. He supports multinational clients in structuring, documenting and defending mainly inter-company financing structures and transactions. Christoph holds a degree in economics and has published in the field of corporate banking. |