In its ambition to retain or even reinforce its competitive corporate tax environment, Switzerland is evaluating a bouquet of replacement regimes to address some of the challenges in its tax dispute with the European Union. In her report, published on December 19 2013, the Swiss Finance Minister proposes, among other measures, the introduction of a licence box on a cantonal level.

Introduction

The proposed Licence Box captures the fruits of the research, development and innovation (R&D&I) process at the end of the value chain, that is, when the R&D&I process results in positive earnings. Hence, the focus of the Swiss Licence Box is on output rather than input support (by a parliamentary initiative, the Swiss government was also advocated to evaluate input support).

It is proposed that the License Box will be open to all legal entity forms, all industries and also includes embedded income and capital gains from a disposal of intellectual property (IP).

To benefit from the preferential tax regime, there are three main questions to be answered: (i) how to get into the box; (ii) how to calculate the income subject to a preferential tax treatment, and (iii) what the expected benefit is.

How to get into the box?

In the process of developing the proposed Licence Box, Switzerland can benefit from the continuing discussions on BEPS and other recent developments in the international tax community and may consider the outcome of such discussions in order to design a robust and internationally accepted tax regime. Particularly with respect to the substance discussions, lots of currently discussed concepts were absorbed in the design of the entry test to the Swiss Licence Box. As a result, not only the question of the qualifying IP but also the question of how much substance and the elements which constitute substance play an important role in the entry test.

Switzerland's Licence Box draws the substance definitions from already existing OECD concepts such as the authorised OECD approach (AOA), the definition of important people functions in the draft report on intangibles, from chapter IX, business restructuring of the OECD transfer pricing guidelines as well as from current discussions in multilateral tax committees at the EU or the OECD.

Since the Licence Box not only focuses on research and development but also on innovation, the Lisbon strategy of the European Union (with the strategic goal of the EU becoming "the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion") and the definitions of innovation according to the OECD Oslo Manual also provided internationally accepted guidance.

As a result of the substance requirements, the assumption of most of the risks inherent in the value chain will be with the entity which qualifies for the Swiss Licence Box since, according to internationally recognised principles, risks follow the functions. Hence, the entity qualifying for the Licence Box assembles most of the important economic activities that produce the income and, as a consequence, the taxable income is in line with the activities that generate it.

Besides substance as an entry test, the question will be, and still is undecided, which IPs will qualify. There are various licence box concepts within the EU which could be considered as a reference point, but from a Swiss perspective, there are mainly three categories. Category I (the narrow box) would include all registered and registerable technical IP rights such as patents and patentable innovations. On the other side of the spectrum, category III (the broad box) would follow the definition of IP rights according to Article 12 of the Model Tax Convention and would include, among others, also know-how, processes and procedures. Most probably, there will be a category II – the middle way – that is, a definition of qualifying IP rights which includes category I, the technical IP rights, but would also include for example designs and trademarks but not know-how and the like. Also with respect to the question of which IPs create substantial value to a business, and hence attract a substantial part of the profit potential, helpful insights can be drawn from the OECD draft handbook on transfer pricing risk assessment, where there is a discussion on common indicators that a company owns valuable intangibles. Important to note is that not only economically owned but also licensing of qualifying IP is eligible, subject to the substance requirements outlined above.

The definition of qualifying IP rights is currently subject to further evaluation by the technical working groups of the Swiss Corporate Tax Reform III project and it is expected that by the end of the first trimester, there will be a proposal to the Steering Committee of the Swiss Corporate Tax Reform III. The Steering Committee includes Widmer-Schlumpf, a representative of the State Secretariat for International Financial Matters, two members of the Federal Tax Authorities and the finance ministers of four cantons (Aargau, Basel Stadt, Wallis and Zug).

How to calculate income subject to preferential tax treatment?

The report discusses two methods: the direct method and the indirect method. The direct method, broadly speaking, follows a net licensing approach where the value of qualifying IP is determined by transfer pricing studies and, expressed in a royalty rate, applied against the taxable operating profit to determine the income subject to a preferential tax treatment.

The indirect method, also known as the residual approach, follows the idea of the UK Patent Box model where, in a step-wise approach, a residual profit is calculated from which all or a part of it will be subject to a preferential tax treatment.

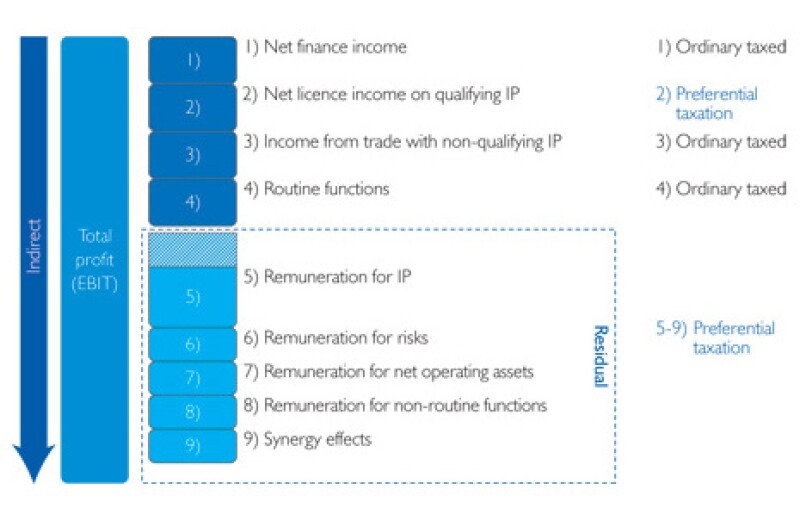

Figure 1 |

|

With reference to Figure 1, the step-by-step approach starts with the operating profit subject to tax from which any net financing income (interest, dividends and so on) is deducted (element 1 in Figure 1). The second step (element 2) includes a deduction of all net licence income on qualifying IP rights and the net profit or loss of the disposal of IP. This amount (that is, net licensing income plus the net profit or loss of the disposal of IP) will be subject to a preferential tax treatment. In step three (element 3), the net income (revenues minus the appropriate costs) from trade with non-qualifying IP will be deducted and ordinarily taxed. What is left (elements 4 to 9) can be qualified as the residual income. However, to calculate the profit subject to a preferential tax treatment, the profit element of routine functions (element 4) needs to be deducted. The UK Patent Box identifies the routine functions, adds a mark-up of 10 % and deducts the respective amount from the residual. Whether the Swiss Licence Box will follow a similar approach or whether the currently discussed lump-sum approach (whereby, let's say, an amount of 20% of the residual after step three is deducted and ordinarily taxed) will be implemented is also subject to further evaluation by the technical working group. What is left (elements 5 to 9) is the residual subject to preferential taxation.

It is important to notice that a transparent approach for both models would increase the international acceptability.

What is the expected benefit?

At this point in time, this is a difficult question to answer. The report made it very clear that the proposed introduction of a Licence Box is a cantonal tax regime, although, the cantonal finance directors still consider a direct involvement on the federal level as a potential solution. Considering a range of effective corporate income tax rates between (roughly) 12% to 24% (including a 7.83% effective corporate income tax rate on federal level) among the 26 cantons, there will be no uniform target rate. However, what can be said is that to calculate the potential loss of tax revenues, the report mentions an approximate 80% discount on the cantonal tax rates which would then lead to an effective tax rate (including the federal rate) of something between 8.4% to 10% on the profit subject to a preferential tax treatment. The report also mentions that the federal government is thinking on ways and means to support the cantons so that the cantons may have more flexibility. This flexibility could lead to a further general reduction of cantonal corporate income tax rates and, together with a discount on the cantonal tax rate to be applied against the residual Licence Box income, could result in an attractive overall tax burden for companies which qualify for the Licence Box.

The discussion on the expected benefit is also influenced by the expected loss of tax revenue for the federal and cantonal governments. Besides the discussion on tax rates, the definition of the qualifying IP also plays an important role; that is, how broadly is qualifying IP defined or, in other words, how much do you need to open the door to get into the box?

Next steps

Within the next six months, lots of technical details will be further evaluated and as a final output, a consultation draft will be prepared. This consultation draft is then subject to a decision by the Federal Council and will later on be released to the public for comments. At this point in time, parliamentary debates on the subject will be expected to take place in 2015. Considering Switzerland's political system (that is, a potential referendum and a public vote), the beginning of 2018 seems to be the earliest time to have the proposed Licence Box introduced.

Although this seems to be a long time, companies are advised to review their current IP and substance structure and to address those issues in a timely manner.

All in all, the current idea of the proposed Swiss Licence Box is an interesting but also transparent tax regime which takes into account recent developments and makes sure that Switzerland remains very competitive on the international tax front to attract foreign investment.

Biography |

||

|

|

Benjamin KochPwC Switzerland Tel: +41 58 792 43 34 Fax: +41 58 792 44 10 Email: benjamin.koch@ch.pwc.com Benjamin is a partner for transfer pricing and value chain transformation within PwC's Tax & Legal Services in Switzerland. His experience includes advising multinational companies on structuring of global value chains, development of global core documentation, migration of intangible property, establishing global trademark royalty schemes and the development of franchising and service fee concepts. Benjamin Koch has substantial experience assisting companies in preventing tax audits and managing international tax controversies through the proactive use of Advance Pricing Arrangements (APAs), tax rulings and Mutual Agreement Procedures (MAPs). Furthermore, Benjamin Koch is PwC's Territory Leader for Tax Controversy and Dispute Resolution and represents PwC Switzerland in the technical working groups of the Swiss Corporate Tax Reform III. |