So how different is tax now? The way in which tax news and information is delivered 25 years on is different, for a start. Websites were well into the future as far as this publication was concerned in November 1989 – the world's first ever website was not launched for another two years. E-mail newsletters? No, the founders were not thinking of those either. LinkedIn? Facebook? Twitter? They were long from being invented in the US, so International Tax Review was definitely not thinking about posting, poking or tweeting.

International

The other ways in which tax has changed have to do with it becoming cross-border. Of course there was international trade 25 years ago and executives thought carefully about tax treatments and what benefits they could eke out from planning a transaction in a particular way. But it was nothing compared to what we have today.

When International Tax Review began in November 1989, some jurisdictions had transfer pricing rules, though most did not. Tax administrators had little to do with their counterparts in other countries; now they meet regularly to talk about issues such as simultaneous and joint audits. And tax havens, or international financial centres, operated without that much scrutiny from outsiders. Now these places have signed numerous tax information exchange agreements – which did not exist 25 years ago either – and do their utmost to convince regulators and the public that they run regimes of the highest probity.

In the past 25 years, tax has moved from the exclusivity of the business pages to the general news pages of the press and to the homepage of any self-respecting news website. It is difficult to consider any matter of public policy or impossible to undertake any corporate transaction without discussing how it will be paid for and how much will have to be paid. One of the ways of doing that is by collecting tax revenue.

Multilateral

Other ways in which tax has changed are:

the critical role multilateral bodies such as the G20, EU, OECD and the UN now play in tax policy development. Such organisations existed in 1989 and were building their influence on tax issues, but it was at nothing like the level of importance they hold now.

the pressure that non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are putting on policy makers to construct the appropriate tax policies in response to problems of our time such as climate change and development and on taxpayers to ensure they pay what is due in every jurisdiction in which they operate; and

the interest the public has taken in how tax is raised and collected. Professionals will argue that the public does not, and will never be able to, understand the complexities of cross-border tax, but the fact is the man on the street wants to know more.

All of this means that politicians and companies have to think carefully now about every tax move they make, whereas 25 years ago they could go about their business untroubled by having to answer to activists or the public on tax.

However, while these all indicate that tax has been transformed, similar issues have a habit of cropping up again and again. International Tax Review has covered them over the past 25 years and we present a selection to you here. They were chosen because of the resonance they have for topics that are still being discussed and fought over a quarter of a century later.

1990

New regime for tax havens in the nineties

Exchange of information and banking secrecy have been hotly debated as international tax rules have been reformed in recent years and jurisdictions have gone after the undeclared assets held by their taxpayers overseas. The 2014 endorsement of the OECD's Common Reporting Standard as the instrument for the global automatic exchange of information has led many to declare that this will end the idea of banking secrecy forever.

This article argued that "properly conducted offshore commercial operations and properly constructed tax mitigation programmes do not need secrecy beyond normal banking and professional confidentiality". It went on to suggest that offshore authorities could strike a deal with other jurisdictions, that in exchange for controlling their activities, suspected tax evaders could be offered tax amnesties. We have seen that many jurisdictions have implementing voluntary disclosure programmes with reduced penalties, without going as far as introducing amnesties.

1991

Multinational tax departments come of age

|

|

"For all acquisitions, disposals and reorganisations, management is quite conscious of the tax effects" |

|

|

A survey in this issue of the magazine of group tax managers from 30 blue-chip European and North American multinationals found that senior management were attaching more and more importance to tax. Where have we heard that before and since? The survey found that 70% of respondents reported to their company's chief financial officer. However, we question the accuracy of our colleagues' numeracy skills in 1991: they described this percentage as "fully two-thirds"! "For all acquisitions, disposals and reorganisations, management is quite conscious of the tax effects," said Vinod Shah, then the tax director of Booker, the UK wholesale food provider. That is still true now.

1992

US 482 regulations send shockwaves around the globe

|

The Internal Revenue Service shocked many taxpayers with its TP revisions |

Twenty three years ago transfer pricing did not occupy the same position in the thinking of tax managers as it does now. The opening up of markets has changed all that and a lot more countries have regulations on intercompany pricing in place now. While any changes to the US transfer pricing regulations would still excite plenty of interest and comment today, the change in 1992 caused consternation because of provisions that, for example, would allow the Internal Revenue Service to consider the combined effect of all transactions between related parties; to take into account the results of prior or subsequent years in its examination of a particular year and to disregard contracts or the absence of contracts between taxpayers.

1993

What do multinationals think of global tax issues?

|

|

"If there is one clear message to emerge from their responses, it is that the US tax system is widely seen as baffling, unworkable, unfair and getting worse" |

|

|

The International Bar Association's conference in New Orleans was the hook for another survey of senior in-house tax advisers. "If there is one clear message to emerge from their responses, it is that the US tax system is widely seen as baffling, unworkable, unfair and getting worse," the survey's author wrote. It seems like nothing has changed. You might get a similar result if you questioned tax managers today.

1994

Water's edge remains unresolved

|

Supreme Court upheld California’s method of unitary taxation |

The question of unitary taxation, a drum that tax justice campaigners are beating hard in 2014, reached all the way to the Supreme Court in the US 20 years ago. In the combined Barclays and Colgate-Palmolive cases, the justices were asked to decide whether California's method of worldwide unitary taxation was constitutional. They decided it was, meaning California could treat the taxpayers as part of a worldwide group and tax them on their operations in California. The arm's-length principle (ALP) versus unitary taxation remains a lively debate for some, even if that was not directly the issue at stake in these cases and despite the fact that the OECD's BEPS work does not contemplate the overturning of the ALP.

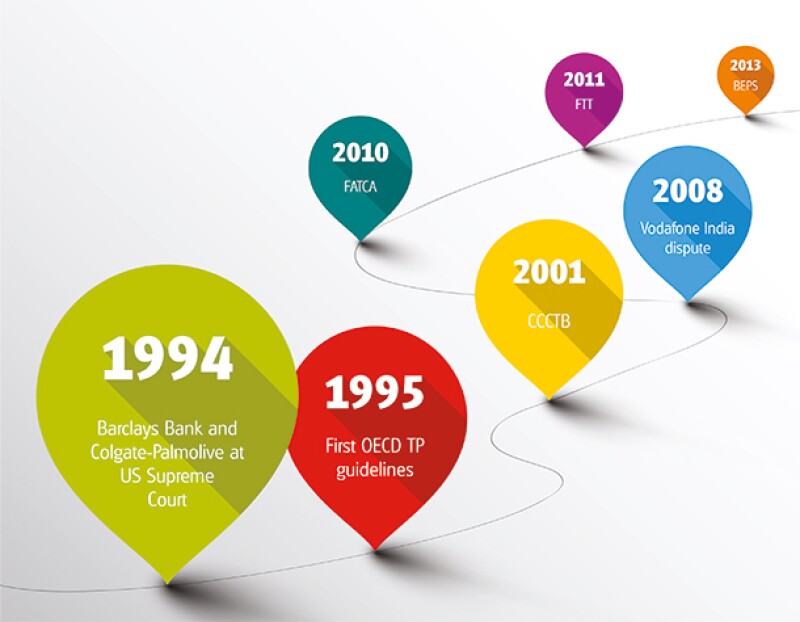

Timeline |

Highlights from the evolution of tax 1989 – 2014 |

|

1995

OECD accelerates tax work; interview with Jeffrey Owens

The OECD was getting going as a force in the production of international tax guidance in 1995 and its influence has only got stronger and stronger since then. "It can play a part where issues cannot be resolved simply at EU level," said Jeffrey Owens, then the OECD's head of fiscal affairs, in the February 1995 interview. That year saw the publication of its original set of transfer pricing guidelines, perhaps the work it was most closely identified with before the G20 commissioned it to lead the BEPS project in 2012.

|

Jeffrey Owens: the first director of the OECD’s Centre for Tax Policy and Administration |

The Organisation's Centre for Tax Policy and Administration was founded in 2001, with Owens leading it as director until 2012, and the rest, as someone may have said once, is history. Plenty of tax activists, academics and others believe the OECD should not be solely responsible for driving international tax reform because it represents the 34 biggest economies in the world. Its opponents believe a strengthened UN Tax Committee would look out for the interests of all countries rather than the biggest. The OECD argues that it has created global fora covering tax administration, VAT, transfer pricing, and tax transparency and exchange of information, which are not confined to members of the Organisation.

1996

Choosing regional headquarters in Asia

If tax competition is a dirty expression in some parts of the world, it has been accepted as a way of life in Asia. Hong Kong, Singapore and China, for example, have long battled with each other to attract companies, particularly financial services and high-tech, to set up in their jurisdiction.

This article looked at how Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan, in particular were hoping to capitalise on the expansion of multinational companies into Asia. Back then Hong Kong had a clear lead over the other two with its corporate income tax rate. Singapore's was 27% and Japan's was 37.5%, while Hong Kong's was 16.5%. While Japan's has come down a little bit, to just under 36%, Singapore's has shown the biggest fall and is now at 17%, just behind Hong Kong's, which is still at 16.5%.

1997

EU tax competition takes centre stage

|

Tax competition in the EU was as much a hot topic 17 years ago as it is now |

Tax competition is a topic that continues to generate strong arguments. Ulrich Wolff, the head of the German tax administration, used an interview in International Tax Review to rail against tax-favourable incentives in the EU, such as the International Financial Services Centre in Dublin, which still exists, Belgium coordination centres, which were phased out by the end of 2010, and financing arrangements in the Netherlands. Ecofin ministers adopted the Code of Conduct on Business Taxation on December 1 1997, which committed their governments to rolling back any harmful tax competition measures and declining to introduce any in the future.

1998

VAT: Where are you coming from?

January 1 2015 sees the introduction of new place of supply rules in the EU on VAT for electronic services, where the tax will be payable in the jurisdiction where the consumer is located, rather than where the producer is. Place of supply has always been a thorny issue. This article analysed the rules in the EU, concluding: "Some of the rules are straightforward and should be quite easy to apply. However, other rules are less clear cut."

1999

Irish tax rate: A phantom menace?

|

Ireland has stuck doggedly to a low corporate tax rate of 12.5% since its introduction |

The Star Wars film of the same name which came out in 1999, lent its title to this article, which tracked how Ireland's corporate income tax rate had changed. The country has been fighting against efforts to raise its 12.5% tax rate on trading income since it took effect at the beginning of 2003. It had been even lower, at 10%, though this only applied to certain industries such as manufacturing, technology and financial services. Taxpayers and advisers discussed the importance of tax in location decisions. Irish practitioners pointed out, as they do now, that Ireland is an open, transparent economy with an open, transparent tax system available to all if the conditions are met. Irish finance ministers have stuck to the 12.5% rate ever since. Michael Noonan repeated that it was not for negotiation in his Budget 2015 announcement on October 14 this year.

2000

Grasp the moment in China

|

Investors streamed into China in the early part of this century as the country started on a series of tax reforms |

This might have been the unconditional advice 14 years ago as overseas multinationals poured into China, but a taxpayer may not follow the same strategy now without realising that China is developing its tax system all the time and is adopting many of the features of tax practice and administration seen in other jurisdictions, such as much-closer scrutiny of transfer pricing and a clampdown on the indirect transfer of shares of a Chinese company.

|

|

"It will be costly for foreign investors to take a wait and see attitude towards China and the WTO, or focus on the talks and formal process itself to the exclusion of other developments worthy of attention" |

|

|

The advice in this article was for overseas companies to rush into China before anything changed after it joined the WTO, which it did on December 11 2001. "It will be costly for foreign investors to take a wait and see attitude towards the WTO, or focus on the talks and formal process itself to the exclusion of other developments worthy of attention," the authors wrote.

2001

CCCTB

The common consolidated corporate tax base (CCCTB), Europe's attempt to harmonise corporate tax collection, has been a long time coming and it is not here yet.

A quick glance back over some of the headlines ITR has produced on the topic since the European Commission announced its intention to introduce a CCCTB in October 2001 shows the slow progress the CCCTB has made. The long and winding road to a common tax base, ITR readers not sold on CCCTB, and Exclusive: "No incentive to opt in to CCCTB" – Vodafone, are just a few that give insight into the troubled lifespan of this tax harmonisation proposal.

The thinking behind a common tax base is that a single set of rules that companies operating in the EU could use to calculate their taxable profits would represent an easing of the compliance burden. Indeed, filing one consolidated tax return for their entire activity in the EU instead of one in each country would reduce the administrative burden, compliance costs and legal uncertainty, and make it easier, cheaper and more convenient to do business in the EU, claimed Algirdas Semeta, the outgoing EU tax commissioner.

|

|

"It’s crucial to look at where the business is going – what’s going to happen in the future and what are the needs of the business – then find a transfer pricing policy that fits with the business and the needs. What you can’t do is use transfer pricing as a tax planning tool. It isn’t one" |

|

|

Member states would retain their sovereign right to set rates, but taxable profits would be divided between the constituent companies of each group by a formula based on assets, labour and sales. More than a decade later, however, the CCCTB has been a topic of largely academic debate since a working group on it held its final meeting in 2008 and a workshop was held in 2010. Despite various steps towards harmonisation within Europe and beyond, an unwillingness to cede a certain level of national sovereignty, among other factors, means the notion is lingering in pre-enactment purgatory.

Pierre Moscovici, who succeeds Semeta as EU tax commissioner on November 1 2014, has listed it among his priorities for action. But he is not the first to do so. To date, the CCCTB has been a topic that is frequently name-checked as an issue to develop, but one which is frequently delayed, though Italy hopes it can produce a compromise proposal on the topic before its presidency of the EU ends on December 31 this year.

As Richard Murphy, the UK tax campaigner, put it in our July/August 2001 special issue covering CCCTB, "the problem is national ego".

The first Global Transfer Pricing Forum

International Tax Review launched the Global Transfer Pricing Forum in Amsterdam in 2001 and it has been held every year since in glamorous locations such as New York, Barcelona, Rome and Berlin, attracting the world's most influential policy makers, taxpayers and practitioners to discuss the most topical issues in transfer pricing.

Speakers and delegates at the first conference talked about the impact of globalisation and the increasing aggression of tax authorities on transfer pricing; intangibles; e-commerce; dispute resolution and advance pricing agreements.

In a comment that has many resonances with what has happened in transfer pricing practice in the past 13 years, a senior manager with KPMG, the first sponsors of the conference, said:

"It's crucial to look at where the business is going – what's going to happen in the future and what are the needs of the business – then find a transfer pricing policy that fits with the business and the needs. What you can't do is use transfer pricing as a tax planning tool. It isn't one."

And look what happens to speakers at the event! Andrew Hickman, also of KPMG, who spoke at the first conference is now head of transfer pricing at the OECD.

2002

Sarbanes-Oxley Act

|

Paul Sarbanes and Michael Oxley, who sponsored the Act |

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act was signed into law by US President George W Bush in reaction to accounting scandals involving companies such as Enron and WorldCom. The Act required, among other things, boardroom certification of the accuracy of corporate financial information. Congress passed the legislation in July, which also restricted firms from offering tax services to audit clients as well as mandating that a company's chief executive officer must sign the company's tax return. Sarbanes-Oxley led many companies in the US to choose different advisers for tax and audit services. Other jurisdictions have adopted measures to ensure independence between tax and audit advice and from mid-2016 EU rules will limit the tax services that can be provided to their clients by audit firms.

2003

What the EU Savings Directive means

After years of fierce debate, 2003 saw the European Savings Directive reach a compromise on banking secrecy and withholding tax. This marked a major step in multilateral attempts to combat tax fraud and increase cooperation between European countries on tax matters.

On January 21 2003 the European Council of Economics and Finance Ministers (ECOFIN) reached agreement on the contents of the European Savings Directive (ESD) and six months later, on June 3, it was finally adopted. It was planned that, from January 1 2004 the member states of the EU had to apply a system of automatic exchange of information on interest income derived from savings by non-residents. The original version actually came into effect in July 2005.

|

|

"The agreement on the ESD and the implementation… is a big achievement and it should ensure that income from savings of EU residents does not escape taxation John Brouwer, Allen & Overy, 2003" |

|

|

A compromise was reached with Austria, Belgium and Luxembourg, which were reluctant to relinquish their bank secrecy rules unless other countries, particularly third countries such as Switzerland, also adopted a similar information exchange system. Austria, Belgium and Luxembourg agreed to apply a withholding tax (WHT) on interest earned by residents of other member states, starting at a rate of 15% from January 2004, moving to 20% from 2007 and 35% from 2010 onwards, with three-quarters of the WHT to be remitted to the country of residence. The ESD was revised in March 2014 to strengthen the rules on exchange of information on savings income by closing loopholes including through the insertion of a look-through approach to prevent the imposition of a legal person or arrangement to distort effective taxation as covered by the directive. This means payments made through intermediary structures such as trusts and foundations would be captured.

Other developments in 2014 have had an impact on the ESD's scope and relevance, too. The updated provisions for the Directive on Administrative Cooperation (DAC) implements the OECD's Common Reporting Standard (CRS), representing the legislative framework for applying the new global standard of automatic exchange of information within the EU.

September 2003 also saw the European Court of Justice rule in the Bosal case that an important statutory restriction of Dutch corporate income tax relief violated EU law. The Dutch Ministry of Finance announced it would adopt new thin capitalisation rules in response to the decision, with significant consequences for acquisition and finance structures.

2004

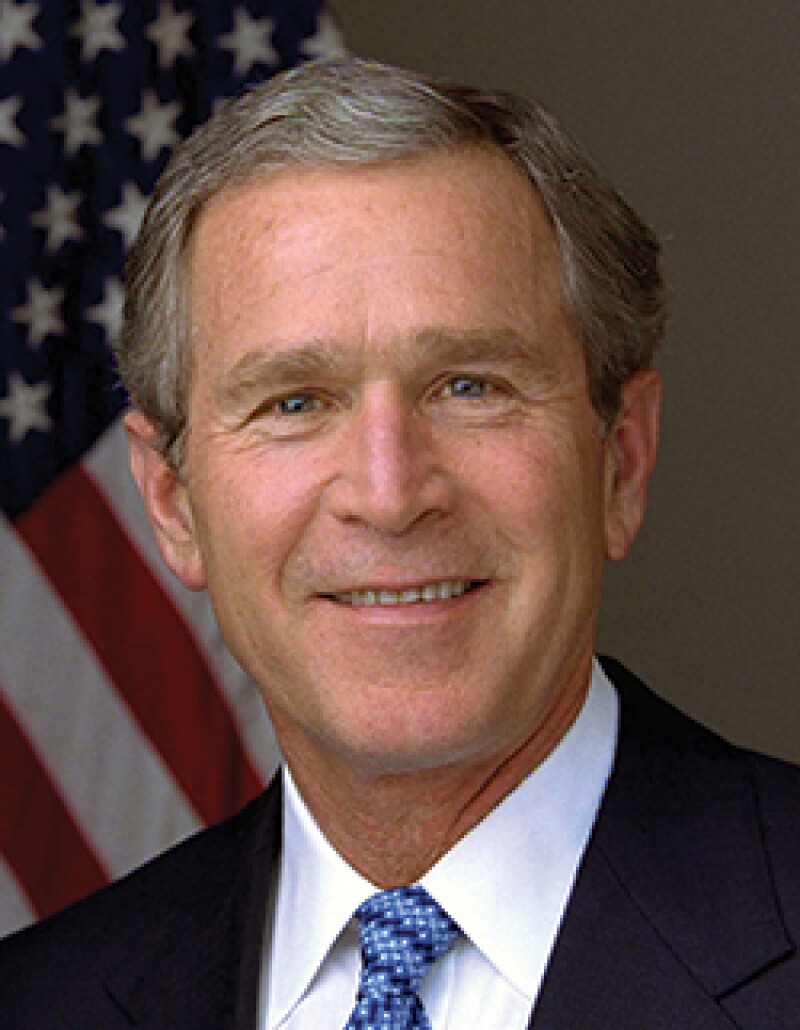

Bush signs new corporate tax law

|

George W Bush signed the American Jobs Creation Act |

In the midst of campaigning for re-election, October 2004 saw US President George Bush sign the American Jobs Creation Act to end the five-year trade row with the EU over the foreign sales corporation (FSC) and extra-territorial income exclusion (ETI) schemes. The 650-page Act was one of the most significant corporate tax laws in nearly 20 years, providing $137 billion in tax breaks over the following 10 years across three broad areas:

Tax relief for US-based manufacturing activities ($77 billion);

Reform of the taxation of multinational businesses ($43 billion); and

A range of targeted business income tax relief ($10 billion) as well as targeted individual tax cuts and excise tax reforms ($7 billion).

The revenue-neutral Act funded these tax breaks by repealing the FSC and ETI provisions (raising $49 billion) and $88 billion in other tax increases that include:

clamping down on specific abusive transactions ($30 billion);

increasing Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and customs-user fees ($19 billion);

closing other corporate and individual loopholes ($15 billion);

shifting and increasing excise tax liability ($14 billion);

general rules assuring more transparency with respect to tax shelter activity ($3 billion); and

other administrative charges ($2 billion).

One of the biggest benefits to many businesses was the 9% deduction for qualified manufacturing income (up to 50% of an employer's wage and salary costs), phased in over five years.

Another attractive element for multinationals was the temporary 85% deduction of dividends received (maximum $500 million of eligible dividends) from controlled foreign corporations (CFCs). This gave US companies a one-year window to repatriate profits from foreign subsidiaries at a significant tax discount.

The Act also simplified the use of foreign tax credits, with two credit baskets – one for passive income and one for general income – down from nine previously.

The main upshot of the Act was that it ended EU sanctions of up to $4 billion a year imposed on the US as a result of the ETI scheme, which the WTO declared an illegal export subsidy in January 2002.

2005

Landmark Marks & Spencer case

|

The M&S case transformed loss relief rules |

In a landmark case before the European Court of Justice, Marks & Spencer (M&S) won a split decision in December in which the court ruled the company should be allowed to offset losses incurred by overseas subsidiaries against its UK tax bill, but only if there is no possibility of using the losses in the jurisdiction in which the subsidiary was set up. The decision transformed loss relief rules throughout Europe. The case is still running and an ECJ Advocate General now wants to overturn the original decision, barring the company from using the losses of a subsidiary. If this reasoning is upheld it would go against a series of cases concerning outward investment and would have implications for the EU's freedom of establishment principle.

In other UK news, 2005 saw the launch of HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC), with the unification of direct and indirect tax collection and administration, aimed at improving the service to taxpayers and cutting down on tax avoidance.

2006

GlaxoSmithKline settles with the IRS and pays out $3.1 billion

|

GSK paid out more than $3 billion |

The $3.1 billion settlement between the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) in October was the largest ever single payment to resolve a tax dispute in US history. The controversy stemmed from whether GSK's profits from Zantac, an ulcer drug treatment, should be attributed to the US or the UK, where GSK is headquartered. The case signalled a marked increase in transfer pricing enforcement by the IRS. In the same month, the ECJ ruled in the Cadbury Schweppes case that the EC Treaty's freedom of establishment rules meant that the UK's controlled foreign company (CFC) rules could only apply to EU subsidiaries that are "wholly artificial" tax arrangements. The ruling forced the UK and other EU member states to look at amending their laws on CFCs.

2007

US adoption of FIN 48 accounting standard

|

FIN 48 cost Lehman $178 million |

FIN 48 directs US reporting companies as to how, under the US's generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), they should represent uncertain tax positions (UTP) in their accounts. In simple terms, FIN 48 requires the disclosure of UTP under the US GAAP. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) introduced the FIN 48 rules for accounting periods commencing after December 15 2006.

The FASB released an update on May 2 2007, with clarification of the term "ultimately settled" cutting compliance time for businesses. The guidance was retroactive, applying from January 1 2007.

The FASB previously required the tax authorities to specifically refer to and clear a tax position for it to be ultimately settled.

But the Board's clarification meant that so long as the tax position was included in a completed audit and the authorities are not questioning its legality then it can be considered ultimately settled.

Companies have been required to invest heavily in extra in-house and external support to ensure compliance with FIN 48. New IT and accounting systems have been implemented at the cost of millions of dollars.

In 2008 Lehman Brothers, which collapsed in the same year, claimed the accounting standard cost the company $178 million.

"On December 1 2007, we adopted FIN 48. The aggregate impact to opening retained earnings from the adoption of this standard was a decrease of approximately $178 million," said CEO Richard Fuld.

2008

Vodafone loses dispute at Bombay High Court

Vodafone lost a case before the Bombay High Court in December 2008, which resulted in the company being assessed a multi-billion dollar tax bill. The case concerned the amount of tax due from Vodafone's purchase of a controlling stake in an Indian phone business.

|

Vodafone’s dispute in India has impacted foreign investment into the country |

UK-headquartered Vodafone paid Hong Kong's Hutchison Telecommunications $11.2 billion in 2007 for a 67% stake in Indian cellular phone operator Hutchison Essar. The Indian authorities subsequently slapped a $2.5 billion tax bill on capital gains from the transaction, claiming the assets purchased were located in India, though the transaction took the form of the acquisition of shares in offshore companies. Vodafone argued that the Indian tax authorities had no jurisdiction to tax the transaction as the deal took place between two foreign companies.

The case went to the Indian Supreme Court in August 2011 and despite a positive ruling for the taxpayer in January 2012, India still tried to tax the transaction and introduced a retrospective amendment to the law in Finance Bill 2012 so that offshore transactions could be brought into the Indian tax net. The retrospective amendment went back 50 years, to 1962.

When Palaniappan Chidambaram succeeded Pranab Mukherjee as finance minister in 2012, he commissioned Parthasarathi Shome to assess the appropriateness of retrospective law amendments, with Shome concluding they should only be used in exceptional or "the rarest of rare cases".

The long-running dispute has had an adverse impact on foreign direct investment into India, which is only now altering the international perception that it is an inhospitable environment in which to do business.

2009

OECD releases new transfer pricing guidelines

The OECD released a proposed revision of several important chapters of the Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations in October 2009. The changes followed two discussion drafts; one issued in May 2006 looking at comparability issues; and another released in January 2008, which focused on transactional profit methods. The 2009 amendments also drew from discussions with commentators during a two-day consultation that was held in November 2008.

The new guidelines updated the existing provisions relating to comparability and profit methods, which dated back to 1995.

An important change was to the hierarchy of transfer pricing methods. The previous guidelines recognised two categories of transfer pricing methods: the traditional transaction methods (found in chapter II) and the transactional profit methods (chapter III). Transactional profit methods (the transactional net margin method and the profit split method) are considered last resort methods, to be used only in exceptional cases.

The 2009 revisions sought to remove exceptionality and replace it with a standard whereby the selected transfer pricing method should be the "most appropriate method to the circumstances of the case".

2010

FATCA included in Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment (HIRE) Act

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) is a US initiative but one with global ramifications.

First introduced in 2010, the initiative only took effect on July 1 2014 after a series of delays. The legislation represents a huge compliance undertaking, and no precedent existed for an undertaking of this scale with such a global reach, but around 90,000 foreign financial institutions (FFIs) – including banks, funds, brokers and investment companies – have registered as FATCA-compliant, and more than 100 jurisdictions have signed or negotiated bilateral intergovernmental agreements (IGAs) with the US to implement the measure.

The original intention behind FATCA was that FFIs would report the information about their US account holders directly to the IRS and Treasury. However, institutions in some jurisdictions pointed out that local law relating to data privacy, for example, would prevent them from doing this and the US developed the idea of bilateral IGAs to make compliance possible.

Under a Model 1 IGA, FFIs will report information about their US account holders to the local jurisdiction, which then exchanges with the US on an automatic basis. In abiding by the terms of a Model 1 IGA they will be judged to be compliant with FATCA and will not have to apply the final regulations.

A Model 2 IGA commits the overseas jurisdiction to "direct and enable" their FFIs to report directly to the IRS about their US account holders. Governments back this up with exchange of information about financial institutions that refuse to comply with FATCA. Under this type of IGA, FFIs will have to apply the final regulations to achieve compliance with the legislation.

The IGAs used as part of FATCA implementation have also been used as models for further information exchange efforts, including the Common Reporting Standard, the method for implementing automatic exchange of information, laid out by the OECD in 2014.

2011

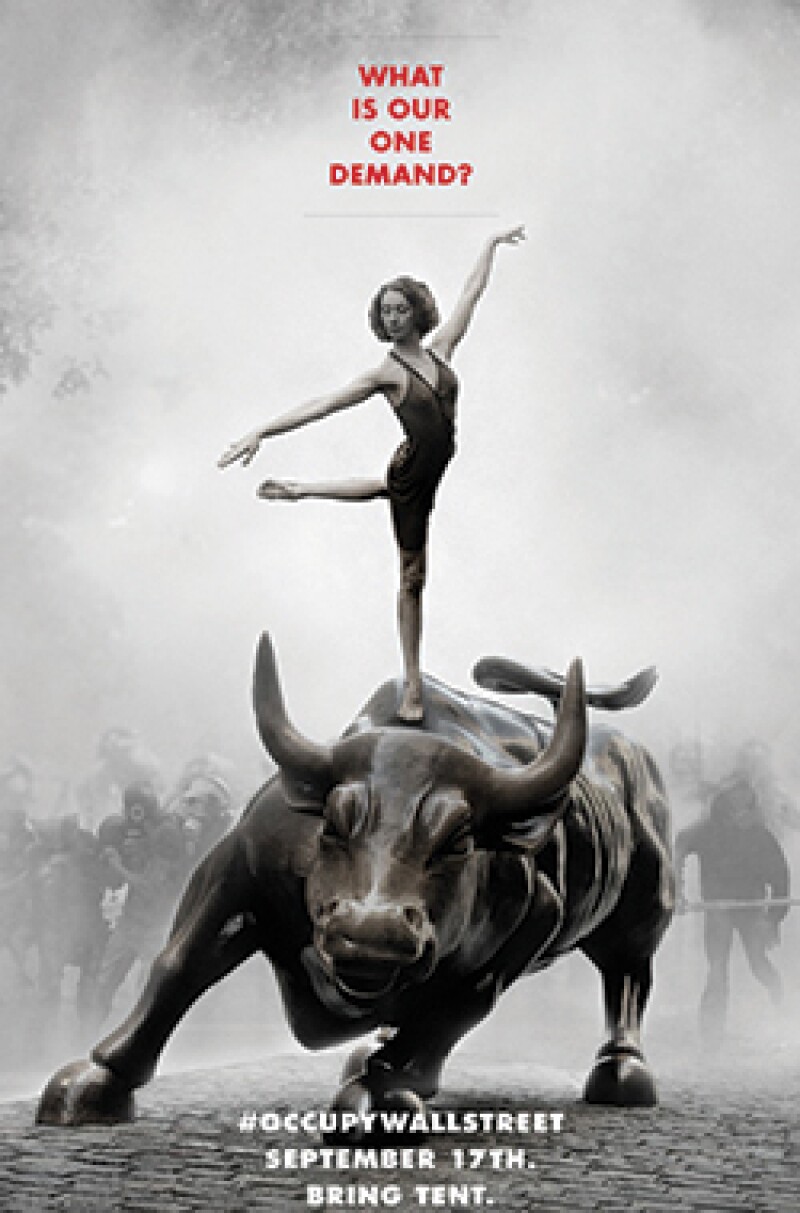

Occupy and Uncut social movements

This was the year during which the tax affairs of multinational corporations catapulted from the more obscure sections of the global media to being splashed across their front pages or leading broadcasting schedules.

For months, it was impossible to leave ITR Towers in London without wading through a sea of tents filled with hippies, socialists, anarchists in masks, punks, students and, yes, ordinary concerned citizens camped outside St Paul's Cathedral. For some they were an eyesore littering the pavement outside one of the UK capital's most famous buildings. For others they were heroes, braving the harsh winter to take a stand. Either way, they sent a message and the media heard it. The new ad hoc, bottom-up social movements, exemplified by Occupy and Uncut, that have sprung up around the world to try to take over stores and Wall Street alike have tax at the heart of their agenda.

The original campers in Zuccotti Park in New York and outside St Paul's have long since been sent on their way, but the issues they brought to public attention cannot be swept aside so easily.

Detailed information about the tax corporations pay is being splashed across daily newspapers and websites like never before.

Corporate tax matters are no longer simply an interest for shareholders or tax officials, but have become one for society at large.

Occupy and Uncut's methods may divide opinion, but they arguably did more than anyone else to focus media and public attention on these issues.

2012

Financial transaction tax (FTT)

The financial transaction tax (FTT), Robin Hood Tax or Tobin Tax, depending on how you want to describe it, was a long-mooted idea in the EU but not until September 2011, when Jose Manuel Barroso, European Commission president, used his annual State of the Union address to the European Parliament to outline the tax, calling it a "matter of fairness", did it become a policy objective.

|

The FTT has been referred to by tax justice campaigners as the Robin Hood Tax |

The UK, which fears the disproportionate impact the FTT could have on the City of London as Europe's largest financial centre, came out quickly to oppose it. George Osborne, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, said any non-global FTT proposal is "economic suicide" and "a bullet aimed at the heart of London". But in spite of this, the once-radical fringe policy gained real momentum in 2012 as 11 EU member states decided to adopt the tax, which would levy a 0.1% tax on trading in shares and bonds and a 0.01% tax on derivatives transactions and which Barroso claimed would raise €55 billion a year.

In a sign of the increasing reach of international corporate tax issues, the FTT became a populist measure that was as much about reining in the financial sector as it was about raising revenues for deficit reduction, tacking poverty and climate change.

Since Nobel laureate James Tobin proposed a tax on currency transactions in 1972, the concept of an FTT has expanded and, as the notion collides with a public sentiment that the financial sector should contribute more towards restoring public finances destroyed in the global financial crisis, it now has backing from four of Europe's five biggest economies.

France and Germany have been the strongest advocates, and with Pierre Moscovici, the pro-harmonisation former French finance minister, about to take over as EU tax commissioner, prospects for FTT implementation are increasing all the time.

2013

G20/OECD project on BEPS

Undeniably the dominant topic in international taxation over the past two years, the base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) project was launched in September 2013 and constitutes the most ambitious attempt to update international tax rules ever.

|

|

"Everything needs to be analysed and revised with the brand new BEPS eyes"Maribel Mendez, Spanish group tax manager for an automotive company |

|

|

The OECD's work on harmful tax competition, which got under way in 1998, is a close relative, but the BEPS project has greater political backing based on full endorsement by G20 leaders and universal acknowledgement that rules have not kept pace with the globalisation and digitalisation of business.

Many question whether developing countries are getting enough say in what is being discussed, but the OECD has put significant effort into making the process as inclusive as possible through discussion drafts, public consultations, webcasts and other updates, though this has made reaching consensus more difficult.

The comprehensive BEPS Action Plan drawn up by the OECD |

| Action 1 Address the tax challenges of the digital economy Action 2 Neutralise the effects of hybrid mismatch arrangements Action 3 Strengthen CFC rules Action 4 Limit base erosion via interest deductions and other financial payments Action 5 Counter harmful tax practices more effectively Action 6 Prevent treaty abuse Action 7 Prevent the artificial avoidance of PE status Actions 8, 9 & 10 Assure transfer pricing outcomes are in line with value creation 8) Intangibles 9) Risks and capital 10) Other high-risk transactions Action 11 Establish methodologies to collect and analyse data on BEPS and the actions needed to address it Action 12 Require taxpayers to disclose aggressive tax planning arrangements Action 13 Re-examine transfer pricing documentation Action 14 Make dispute resolution mechanisms more effective Action 15 Develop a multilateral instrument |

|

|

"This will not please the NGOs but the CbCR information will go to tax administrations only. This is extremely sensitive information"Pascal Saint-Amans, director of the OECD’s Centre for Tax Policy and Administration, acknowledges the compromises that have been reached to implement a new era of tax reporting for international business |

|

|

Of course, much of the work to tackle BEPS remains to be completed. The 2014 deliverables were fairly well-received, with the OECD praised for sticking to its ambitious timeline for bringing coherence, substance and transparency to international tax rules around the world, and for managing to reach a degree of consensus without initial proposals being watered down. The September and December 2015 deadlines are certain to become landmark dates in the history of the evolution of international tax rules.

2014

Common Reporting Standard

The OECD unveiled the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) in July to implement the global automatic exchange of information. The standard, which largely builds on FATCA, was first presented to, and endorsed by, G20 finance ministers in February 2014.

Early adopters of the CRS, of which there are 50 countries including 26 of the EU's 28 member states (though not the US), have committed to start exchanging information under the instrument from 2017, with a further 20 jurisdictions saying they will start exchanging information from 2018.

On an annual basis, financial institutions, including custodial institutions, depository institutions, investment entities and specified insurance companies, will be required to report certain information from accounts held by individuals and entities, including trusts and foundations, to their national governments. The CRS will see governments exchanging this information, which will include details of balances, interest and dividends and sales proceeds from financial assets.

At their October meeting, EU finance ministers also agreed to adopt the draft Directive on Administrative Cooperation (DAC), which will incorporate the CRS and enable mandatory automatic exchange of information between member states' tax authorities once national legislation is in place.

UK officials have described the DAC's objective as "switching off" the reporting requirements under the EU Savings Directive.

ITR coverage in July included exclusive interviews with the OECD's Achim Pross, the man responsible for several of the BEPS action items and for the OECD's work on information exchange more broadly, and Jorge Correa, one of the principal drafters of the new standard.