Multinational enterprises (MNEs) in the industrial products and construction (IP&C) industry typically sell their products to other businesses (back-to-back) and often make use of ‘routine sales companies’ in certain markets for their distribution activities. In parallel, the importance of (and value attached to the) customisation of products, project engineering activities, and software integration into the products has also been steadily increasing in the IP&C industry.

From a transfer pricing point of view, the use of benchmarking studies as part of a transactional net margin method (TNMM) analysis is a very common approach to determining an arm’s-length return for these functions. However, creating benchmarking studies, especially assessing qualitative comparability factors, can be a complex and costly endeavour and the results can be the subject of protracted discussions during tax audits on a global scale.

Amount B is an initiative developed by the OECD that aims to simplify the determination and auditing of profits from baseline distribution functions performed in market jurisdictions. It provides a standard mechanism for determining marketing and distribution-related profits, allowing for variation in national adoption, as a safe harbour or a compulsory rule. According to the OECD’s Pillar One – Amount B: Inclusive Framework on BEPS report published in February 2024, amount B is intended “to simplify the application of transfer pricing rules with regards to baseline marketing and distribution activities, alleviate administrative burden, cut compliance costs, and enhance tax certainty for tax administrations and taxpayers alike”.

Amount B therefore attempts to simplify the transfer pricing of certain wholesale marketing and distribution activities by providing agreed returns to the source country for such activities. However, it remains to be seen whether the OECD's attempt to harmonise distribution margins with the newly designed amount B approaches will alleviate the compliance burden attached to benchmarking studies for MNEs in the IP&C industry in practice. Vague scoping definitions, complex calculation (and segmentation) mechanisms, and the potential for globally inconsistent implementation of amount B could instead have the opposite effect of increasing tax uncertainty and requiring even greater effort by IP&C MNEs to defend their transfer prices globally.

This article briefly outlines the conditions under which transactions in the IP&C industry can qualify for the OECD’s amount B and the OECD’s proposed target margins. It then discusses (based on a large-scale data analysis) how proposed amount B target margins compare to actual margins earned in the IP&C industry in recent years, as observed in TNMM benchmarking studies.

Amount B: industry products in scope

The industry grouping system under the OECD’s amount B approach is a critical factor for determining the applicable pricing margins for intragroup transactions within an MNE. The OECD framework for determining applicable distribution margins groups in-scope distribution transactions based on:

Their relevant industry grouping; and

Their asset and operating expense intensities.

The industry grouping system is largely dependent on the nature of the distributed goods. A wide range of tangible goods and industries – ranging from groceries to medical technology, and household consumables to electrical components – falls within the reach of the guidelines. The only excluded industries not covered by the OECD’s industry groupings are the commodity sector, software/service vendors, insurers, financial traders, and businesses involved in R&D.

To determine the appropriate target operating margin, MNEs will have to identify the relevant industry grouping(s) and the applicable vertical column(s) of return on sales (RoS) in the OECD’s pricing matrix (see Pillar One – Amount B: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, Table 5.1). If the products distributed fall into more than one industry grouping, a weighted-average return should be calculated. Products such as medical machinery, industrial machinery, and industrial tools and components are likely to be attributed to group three within the industry grouping framework. Other products such as packaging, textiles, mixed products, and components are likely to be attributed to group two.

This product grouping approach allows for a systematic determination of transfer pricing benchmarks, thereby simplifying the process for all parties.

Proposed target margins in the OECD’s amount B pricing matrix

The amount B pricing matrix sets an RoS varying by industry group and factor intensity (approximated by operating asset intensity scores (OAS) and operating expense intensity scores (OES); see Pillar One – Amount B: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, tables 5.1 and 5.2).

Target margins under the new amount B regulations, as proposed in the OECD’s pricing matrix, are as follows:

Industry grouping | Industry grouping 1 | Industry grouping 2 | Industry grouping 3 |

(A) High OAS/any OES>45%/any level | 3.50% | 5.00% | 5.50% |

(B) Med/high OAS/any OES 30–44.99%/any level | 3.00% | 3.75% | 4.50% |

(C) Med/low OAS/any OES 15–29.99%/any level | 2.50% | 3.00% | 4.50% |

(D) Low OAS/non-low OES<15%/10% or higher | 1.75% | 2.00% | 3.00% |

(E) Low OAS/low OES<15% OAS/<10% OES | 1.50% | 1.75% | 2.25% |

Observations regarding the profitability of distribution entities within the IP&C industry

To understand the potential impact of amount B on the future profitability of distribution entities within the IP&C industry, it is a good starting point to examine average profitability in the sector. The authors have evaluated their internal database of over 170 TNMM benchmarking studies from the past 15 years and found that routine distribution margins, on average, range between 3.52% and 12.50%, with a median of 6.63%. By comparison, the standardised profit margins in the OECD’s pricing matrix are comparatively lower, ranging from just 1.5% to 5.5%.

As discussed, within the IP&C industry, distribution activities often require project engineering activities, detailed customer requirements analysis, product demonstrations, etc., all of which lead to a requirement to hire highly trained local personnel, which can drive up the operating expenses incurred by a distribution entity. These activities often necessitate maintaining local warehouses, testing facilities, demonstration units, etc. As such, IP&C industry participants typically have higher average OAS than other MNEs with less asset-intensive distribution activities.

Different transfer pricing approaches are already observable in the market in this regard. Some companies even view these activities as being entrepreneurial functions (hence excluded from the TNMM approach, which is typically reserved for more routine distribution activities). Others test these functions separately; for example, using the cost-plus method.

Observations regarding distributors’ operating asset/expense intensities in the IP&C industry

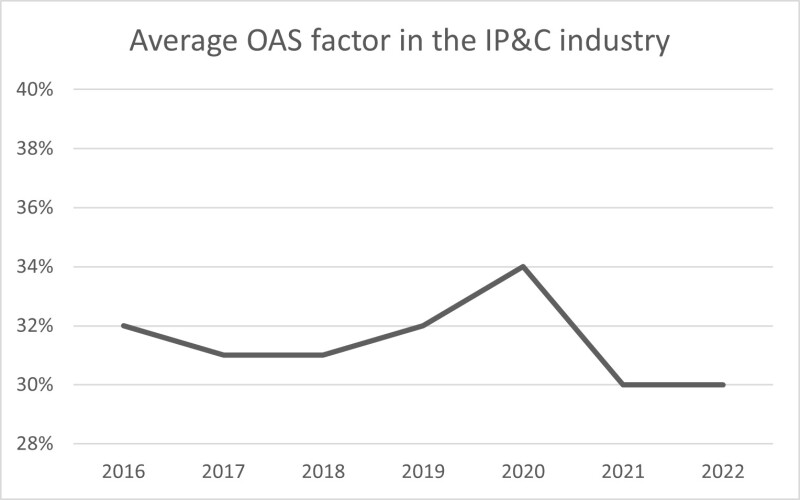

Based on an evaluation of the financial data of more than 4,000 routine distribution entities in the IP&C industry for FYs 2016–22 retrieved from the TP Catalyst database in May 2024, the authors found that the median OAS factor in the IP&C industry among comparable companies with distribution activities is around 30% to 34%, as shown in the illustration below.

As discussed above, this relatively high OAS factor implies that a company operates in an asset-intensive industry in which high initial investments are required for its distribution activities, which may be the case for machinery and equipment.

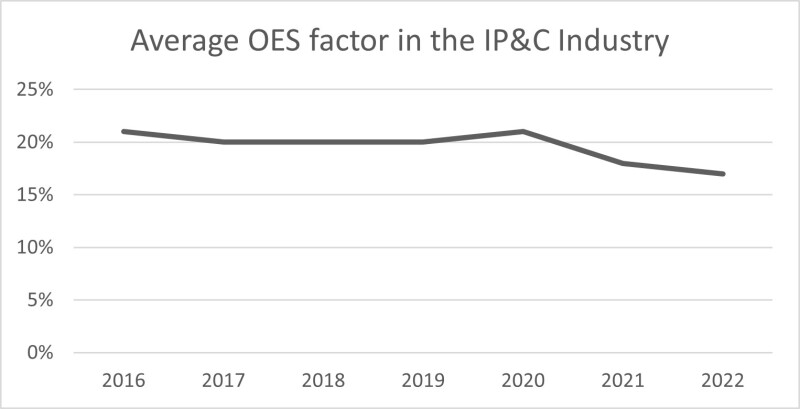

Given that the OECD also considers the OES factor, the authors performed an analysis of the average OES factor in the IP&C industry over the same period, using the same comparable companies. The result can be found in the illustration below.

The data shows that the OES factor in the IP&C industry is also relatively high, possibly indicating that a high percentage of revenue is consumed in operating activities. Potential reasons for this could be high sourcing costs, handling and storage costs, and other administrative and sales expenses. Since the distribution and sales activities for IP&C products are often highly specialised, a high OES factor is not surprising. The high OES factor may even lead to exclusion from the scope of amount B in certain jurisdictions, depending on local regulations and respective OES thresholds.

The analysis above provides valuable data points that could be useful for MNEs in the IP&C industry evaluating the implications of transitioning to the new amount B guidelines. It should be noted, however, that special effects caused by the pandemic in FY 2020 have not been excluded.

Proposed target margins in the OECD’s amount B pricing matrix

When analysing the classification of the average distribution company in the IP&C industry according to the amount B pricing matrix, it is highly probable that this company would fall under intensity factor B and industry grouping two or three. This implies that the average target margin would likely be between 3.75% and 4.50% under amount B, significantly lower than the average margins achieved for distribution functions in the authors’ analysed benchmarking studies.

Amount B target margins also represent very narrow ranges that can essentially only be achieved through the calibration of transfer prices during the year and possibly even year-end adjustments. Especially for MNEs that have not previously performed strict calibration and year-end adjustments, significant changes to internal controlling and KPI logics (often to set local incentives) will need to be made to adhere to amount B margins.

From the perspective of local revenue authorities, the proposed amount B approach could also lead to interesting discussions as lower tax revenues may result (based on lower target margins). This could lead to increased scrutiny of the relevant scoping criteria and revenue authorities seeking to argue that certain transactions would not meet the amount B scoping criteria, such that other benchmarks (higher margins) may be required in assessing the arm’s-length nature of a transaction.

Furthermore, the industry’s demarcation difficulties with respect to project engineering, after-sales service, and customising activities will not disappear under amount B. The fundamental question will continue to arise as to whether an aggregation of these functions with the sales function is appropriate, or whether operational reasons instead necessitate segmentation. Certain services, such as project engineering and after-sales service, therefore may not fall under the scope of amount B. However, these value-adding activities are core aspects of distribution functions, warranting arguably higher or additional return. The debate around the inclusion of these services raises questions on the potential applicability of amount B regulations in the future.

Actionable recommendations for tax and TP departments

Tax and transfer pricing departments should pay heed to the following recommendations:

They should observe how countries position themselves regarding amount B in the future. In some countries, amount B may be mandatory; in others, it could be an optional safe harbour.

Tax departments should have a clear understanding of the local business model and, specifically, ascertain the extent to which local functions such as project engineering, assembly, customising, and after-sales services are being provided locally. Knowledge of how these functions are treated and remunerated under the current transfer pricing model (supported by robust documentation to be able to properly demonstrate and substantiate why amount B should not apply) will be critical.

The interaction between operational transfer pricing (and corresponding margin steering) and management reporting should be examined, especially against the backdrop of a possibly significant reduction in local profitability under amount B.

The benchmarking approach should be consistently and uniformly adopted throughout the group and clearly documented to be able to meet any questions and challenges from the local tax audit.

The industrial products and construction industry’s outlook under amount B

The intricate and prescriptive nature of the amount B approach requires individual jurisdictions to consider its implications when amending their national legislation. Despite its complexity, the consistency and transparency brought about by amount B could significantly improve the international taxation environment, promoting balanced global economic profit allocation.

As the implementation of amount B is still in its early stages, debates surrounding its scope and application continue to unfold. Notwithstanding this, the influence of amount B on the decisions made by MNEs regarding their business models and strategies is undeniable. Even if not implemented in a country, local tax authorities can still refer to the OECD guidelines and target margins as communicated under amount B.

The amount B pricing matrix may be used as a ‘soft law’ benchmark for transfer pricing reviews. This underscores the need for robust mechanisms to manage and monitor transfer pricing activities. It is crucial for MNEs to have a comprehensive understanding of their global business operations and key value-adding functions, and to have comprehensive pricing analysis and documentation in place to proactively identify and mitigate potential risks. The aim is to define a sustainable transfer pricing approach that accurately reflects their business operations and minimises risks.

The expectations surrounding the amount B framework underline the need for international consensus and cooperation, which are critical for the success of these regulations across all jurisdictions. In implementing the amount B approach, companies that currently use the TNMM and target specific profitability margins for their distribution entities must now carefully factor in the potential impact of, and align their strategies with, the stipulations under the amount B guidance.

In conclusion, while adjustments may be required, the amount B approach may be an effective tool for the future of international tax governance.

Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (DTTL), its global network of member firms, and their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte organization”). DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) and each of its member firms and related entities are legally separate and independent entities, which cannot obligate or bind each other in respect of third parties. DTTL and each DTTL member firm and related entity is liable only for its own acts and omissions, and not those of each other. DTTL does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about to learn more.

This communication contains general information only, and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (“DTTL”), its global network of member firms or their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte organization”) is, by means of this communication, rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your finances or your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser.

No representations, warranties or undertakings (express or implied) are given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information in this communication, and none of DTTL, its member firms, related entities, employees or agents shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage whatsoever arising directly or indirectly in connection with any person relying on this communication. DTTL and each of its member firms, and their related entities, are legally separate and independent entities.

© 2024. For information, contact Deloitte Global.