Components suppliers have become increasingly important members of the auto ecosystem. As such, suppliers not only manufacture and deliver auto parts for their original equipment manufacturer (OEM). Rather, successful suppliers maintain excellent product design, customer relationship management and are able to manage and control their relationships with the OEMs besides the delivery of defect-free goods. Suppliers are creating value as supply chain and procurement specialists in just-in-sequence production processes, as key account managers supporting research and development (R&D) activities in partnership with OEMs, or as outsourcing partner for low-tech parts creating economies of scale.

The automotive industry as a key sector in today’s world, has progressed in the last decades by successfully overcoming several challenges following the effects of political and economic events that took place in the last decades and by adapting their business model to the new demands of consumers.

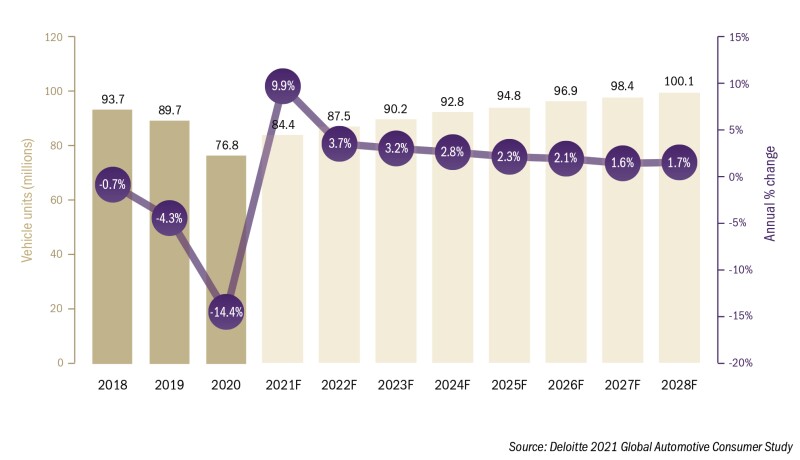

The recent disruption in global markets due to the COVID-19 pandemic will not be different but may lead to a reconfiguration of the business models observed so far as countries across the globe are handling the crisis differently and some will recover from local shutdowns earlier than others. Not surprisingly, this affects economic activity, household spending and employment growth. Overall, after some years of declining sales, the outlook for the next decade is of continuous growth in the automotive sector (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Global light vehicles sales and growth (2018 - 2028F)

Other factors influencing the level of future car production despite the COVID-19 pandemic are the developments of digitalisation and the evolution of mobility and connectivity. OEMs are facing questions like: Will shared mobility become a significant alternative to owning a car? Will vehicle sales move online anytime soon? Will technological potential on autonomous driving come rapidly to the market? Will environmental policies increase the pressure to change to more sustainable and environmentally friendly vehicles?

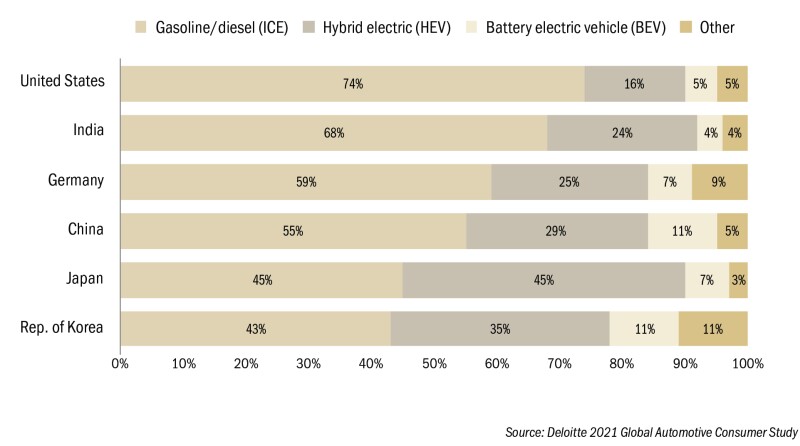

As Deloitte’s 2021 Global Automotive Consumer Study shows, due to the pandemic and other trends in demand, consumers may revise their consumption intentions and cause a slowdown of the previous rising trend on technology cars. Despite the current hype of electric vehicles (EVs) and hybrid electric vehicles (HEV), it is still uncertain how fast the demand for new drive technologies will grow in the short run and when it will overtake gasoline or diesel vehicle production.

As Figure 2 shows, demand for different powertrains may vary between territories. In general, the preference for new powertrains are higher in Asian counties than in the Americas. The intention to buy a gasoline or diesel vehicle may, however, jump back up, as consumers are looking for comfort of affordable, tried and tested technologies in uncertain times like today.

Figure 2: Consumer powertrain preferences for their next vehicle

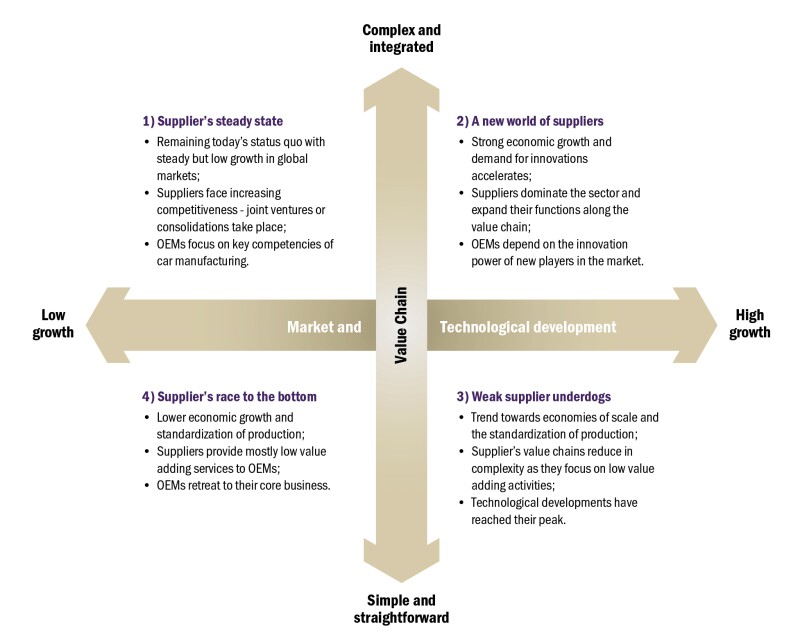

Demand patterns will determine where vehicles will be developed, manufactured, and distributed and how interaction between OEMs and suppliers will look like in the future. This makes predictions for the automotive industry a multi-dimensional problem: for one, market growth and technological developments influence consumers’ purchasing power and preferences.

Secondly, consumer preferences for certain products will influence the complexity of future value chains and therefore the constellation in which OEMs are working together with component manufacturers. Figure 3 summarises the main attributes of the relationship between market development and the complexity of suppliers’ value chains. Depending on which effect will dominate future developments, business models will be subject to changes which will also bring up different transfer pricing (TP) challenges. In the following section we will discuss the resulting TP implications from each of these states.

Figure 3: Scenarios for automotive suppliers in the next decade

Possible scenarios for the supplier market

Scenario 1: Supplier’s steady state

In a first scenario, global markets will develop as they did in recent years remaining low but steady growth rates with rising demand for technology as expected. Trade environment between countries are unchanged. Suppliers’ position in the market is steady, there is no overly rising demand for new technologies. Traditional supply chains remain relatively complex as they currently are due to the fact that intellectual property (IP) is spread across the globe. A major role will then play geopolitical developments shifting economic growth to those countries which offer a secure and stable business environment. Trade wars, barriers to enter new markets, import restrictions or increased tax obligations will force OEMs and suppliers to revise their value chains and secure their profits.

In this situation some countries will be more attractive to make business than others and we would expect companies to centralise their IP more and more as the political environment is becoming unstable. This is especially true for suppliers serving as technology leaders rather than pure outsourcing partners. Their global footprint will decline and so will their margins with more and more competition.

TP specialists will have to think about the value contribution of group entities along the value chain and how to allocate thin margins to them. What is gaining more and more importance within the OECD besides the analysis of functional and risk profiles is the question of substance and the ability to take and control risk factors of a group’s operations.

Control in this regard is defined as the ability to decide on, to take risks and manage risks, and to exercise these decision making functions (cf. e.g. OECD Guidelines chapter VI, or the German administrative principles on TP 2021, note 3.5). It is particularly important to ensure that group members actually bear responsibility for the measures to be taken and the costs incurred in the event of the risk in question occurring. Only in this way an entitlement to the residual profit arise or a routine remuneration can be justified.

Scenario 2: A new world of suppliers

If, instead, the world advances in the direction of a more open market and strong economic growth, where demand for new technologies in automotive vehicles accelerates, the position of suppliers enhances in comparison to the previous scenario. Again from the previous example, in this scenario we can picture a world where consumers’ ecological perception and preferences for emission free driving increase, giving the way for new technologies within modern cars where software and app related companies will play a major role for the automotive sector. Economic growth and political stability ensure people have the purchasing power to buy all the comfort and convenient components they desire. Competitiveness across companies will then increase as new players are entering the market and value chains are being reinvented as new goods are entering the scene.

From a TP perspective, the appearance of new players in the market can heavily affect the valuation of intangibles of both the old stagers and the rookies in the field. As some suppliers will be evolving and gaining market shares, others will loose and see revenue figures plummeting if they don’t react quickly to consumers’ and OEMs’ requirements. This will also affect the value of these firms and their IP.

We often see IP being transferred across countries without really changing the overall business model, hence, no major changes in the structure of personal functions. When legal ownership in IP is shifted, usually the transferring entity is stripped down to routine character. TP specialists will more often have to answer the question what share of the overall group profit an ex-entrepreneur should get. Especially emerging markets will see their stake in the global profit cake shrinking and companies should be prepared for tax authorities challenging any transaction which is diminishing their tax basis.

When it comes to the participation of new players or startups in the market, TP planning will become more important. New TP models will need to be established. Planning, documenting and defending TP systems will be new to those who are just starting to become a multinational enterprise (MNE).

Although this is an extreme scenario it gives an idea of what some market participants might be confronted with given the developments laid out above.

Scenario 3: Weak supplier underdogs

Contrary to the second scenario where suppliers are the winners in terms of market dominance, the expansion of markets and growth of sales of vehicles can also lead to a strengthening of OEMs dictated by the trend towards economies of scale and the standardisation of production. If EVs’ technologies become standardised and the great leap forward in battery and software development will reach its peak soon, OEMs would be able to replicate themselves the required technology and perform backward integration along the value chain instead of relying on third party suppliers. This evolution would make OEMs market leaders, reducing the number of suppliers needed to compete in technology. As a consequence, the value chains of suppliers would reduce in complexity as they would be focusing again on efficiency gains and less on innovation. They become “underdogs” and cannot cope anymore with the competition of large scale OEMs outsourcing less to third parties. A number of market participants will likely disappear or merge with others in this scenario.

TP models of suppliers should become fairly simple when less valuable IP is involved and more low-value adding services are performed. OEMs won’t pay for the risk management functions of suppliers as they increasingly take over such activities in-house along with the manufacturing of tech related parts. OEMs will also take control of the quality and quantity of components manufactured as well as other risk management functions. Despite the lower complexity in suppliers’ value chains, we can expect disputes where companies are scaling down and restructuring. One can expect a debate around what activities are high value adding versus low value adding and who is entitled to receive a larger share of the group profits. Again, it will become more important than ever to have precise and sound analysis of people functions and their ability to take control over risk in order to put forward counter arguments during tax audit disputes.

Scenario 4: Supplier’s race to the bottom

The final scenario builds on the last one but adds to it a negative forecast of economic and technologic growth, together with a reduction of international trade hitting both suppliers and OEMs. In our example, the demand for vehicles with excessive technology and optional equipment declines as a result of decreasing purchasing power or a reduced demand for new technologies due to bad experiences or bad publicity. For instance, one could imagine a scenario where EVs’ batteries prove to be defective and harmful, software products or apps are being manipulated or hacked, or autonomous car driving causes accidents with personal injuries. If such things happen and people become reluctant to consume new technologies paired with a decline in disposable income suppliers will be facing tough times.

As the overall market declines and profits are shrinking, OEMs retreat to their core business, i.e. the development, engineering and manufacturing of light vehicles with combustion engines. Worldwide, suppliers will close down business and reduce complexity along their value chain as mostly low value adding services are requested by OEMs.

TP discussions will focus on the allocation of losses arising from these bad conditions. In particular, there is already heated debate around the question who should bear costs for shutting down facilities, how subsidiaries should participate in bad debt losses or the repayment of government R&D credits where research centers are closing. In cases where there is still a little profit to expect, exit taxation will be imposed stressing MNEs cash reserves. In essence, debates during tax audits can be expected to become harsher in times where there is little profit to share between countries compared to times where there is plenty of taxable profit in the industry.

Summary and outlook

Changes in the automotive market are dependent on developments of the economic environment, the geopolitical setting as well as consumers’ preferences. However, all these factors are difficult to foresee. Depending on the actual outcome the future of suppliers in the market and their business models will be subject to specific changes.

Pitfalls for TP managers emerge wherever value chains are restructured, IP is being transferred or made available to others or functional profiles are about to change. MNEs need to carefully observe market trends and evaluate where TP risk could arise. As always, sound and contemporaneous documentation of facts and circumstances as well as anticipatory planning efforts are key to success in future tax audits and the avoidance of disputes with tax administrations.

Click here to read Deloitte's TP Change Management in Industries guide

Stephan Habisch |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Deloitte Germany T: +49 211 8772 3261 Stephan Habisch is a partner at Deloitte Germany. He joined Deloitte in 2014 and is a partner in Deloitte‘s German TP practice in Düsseldorf. He graduated as a certified tax advisor (StB) and has approximately 11 years of professional experience. Stephan advises German outbound enterprises in TP planning and implementation projects, in TP restructuring and implementation projects, and is experienced in the associated implementation of TP compliance programmes. Stephan’s clients includes large German MNEs, mainly in the automotive industry, but also covering clients from the consumer business and pharmaceutical industry. In addition, he is responsible for the Operational Transfer Pricing Initiative of Deloitte Germany. |

Andreas Göttert |

|

|---|---|

|

Senior manager Deloitte Germany T: +49 151 5807 2616 Andreas Göttert is a senior manager at Deloitte Germany. Andreas joined the TP team in Munich in March 2017. He advises on the conception, implementation and adjustment of TP systems, the valuation of tangible and intangible assets and the preparation of global TP documentation reports as well as their defense in internal and external audits. Prior to joining Deloitte, Andreas spent several years in TP at another Big Four firm and was previously employed by an industrial company, where he also worked in the area of TP. |