China's digital economy has been rapidly expanding and evolving, with new operating methods and technologies continuously emerging and adapting at a breathtaking speed. Different government bodies have been making efforts to encourage the overall growth of the digital economy, while at the same time seeking ways to regulate and in some cases, restrain certain types of digital transactions. These developments have made it extremely challenging for the Chinese tax authorities to administer tax collection under the existing tax regulatory framework. This being said, the digitisation of the economy, and of the tax authorities' own work processes, hold out the promise of radically improved enforcement effectiveness in the future. This chapter examines a number of the notable challenges being posed by digitisation to China tax management, and evaluates its long-term impact on Chinese tax administration and enforcement.

China's rapid digital economy development

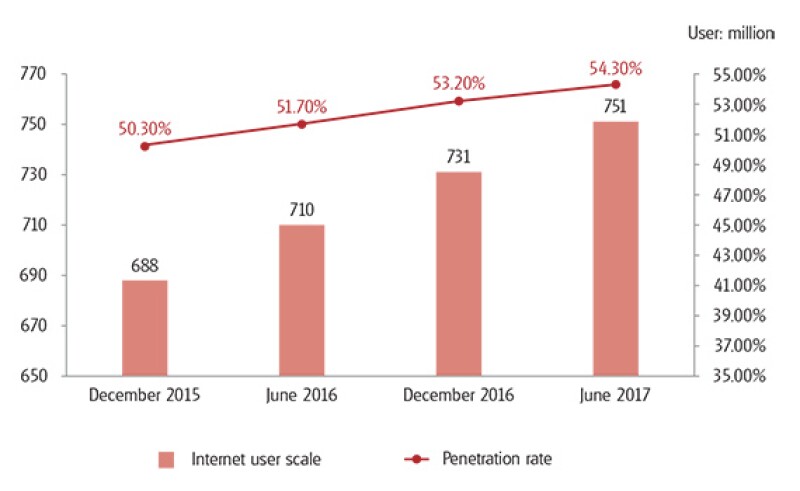

In today's China, the internet has penetrated every corner of life, and digitisation continues to proceed at a breakneck pace. According to the 'Statistical Report on Internet Development in China', issued by the China Internet Network Information Centre in June 2017:

China had 751 million internet users, with an increase of 20 million in the first half of 2017;

The internet penetration rate reached 54.3%, up 1.1 percentage points from the end of 2016;

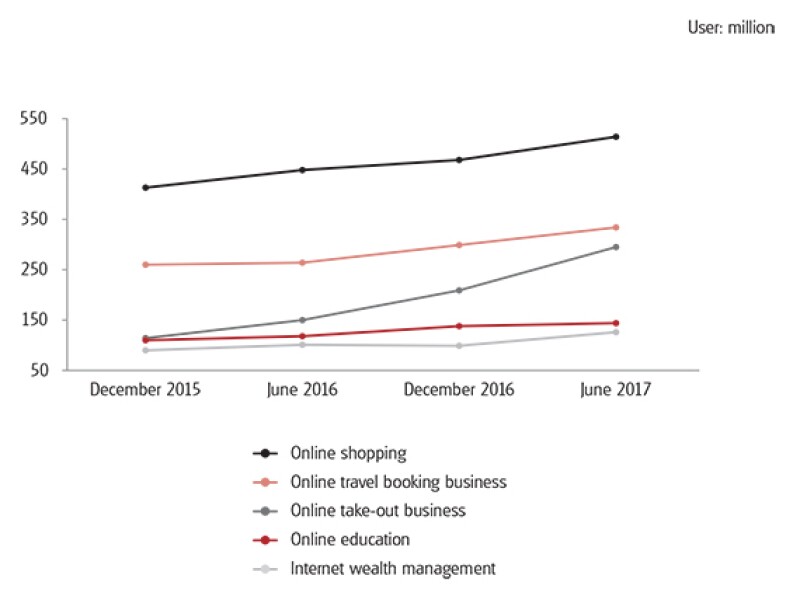

The number of users of online shopping, online take-out business and online travel booking business increased by 10.2%, 41.6% and 11.5% respectively in the first half of 2017;

China had 126 million internet wealth management users, with a semi-annual increase of 27.5%;

Up to 61.6% of offline shopping transactions are settled via mobile online payment; and

China had 144 million online education users, 278 million online taxi sharing users, and 106 million online bicycle sharing users.

The digital economy has completely changed the traditional ways in which many businesses are run in China and have become part of daily routine. This has an impact on the ability of taxpayers and authorities to effectively apply and enforce the existing, outmoded tax rules and guidance.

Diagram 1

Diagram 2

Challenges with the tax classification of revenue

With the proliferation of new and unique digital business models, challenges have emerged with the tax classification of revenue, which is essential for applying the appropriate tax rate. This is true for many countries, including China, and is especially an issue for indirect tax. The following factors often contribute to these challenges.

Industry regulation and its tax impact

China has a highly regulated economy and the regulatory classification of industries, products and services has roll-on effects for their tax treatment. However, both the regulatory and tax regimes are struggling to keep up with the pace of China's digital economy evolution. This leads to many areas of conflicting interpretation and uncertainty when seeking to identify the appropriate Chinese tax treatment.

Online-to-offline (O2O) business models cover a vast array of situations in which a purchase is made online and consumed offline. Platform companies set out goods/service information, etc. to consumers via their online stores. Consumers select goods or services online and settle the payment online, then verifying and consuming the goods or services offline.

A typical O2O business model is the online car sharing business under which the platform company (e.g. Didi in China, and Uber in many other jurisdictions) links a driver with a rider (i.e. customer) via its mobile technology/application. It is often debated in China whether the revenue earned by the platform companies should be classified as income from information and technology services (e.g. value-added services provided via information systems), or as agent commission, or as income from transportation services. Development in the industry regulation has played a role in the debate.

From the business perspective, the car sharing application owner just offers and operates a mobile application platform, by means of which the riders and the drivers can be matched with each other. The platform company itself does not own any cars or employ any drivers through which the transportation services are rendered. From a China legal/regulatory perspective, the platform company is typically registered as an information and technology service company, and applies to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) for an internet content provider (ICP) licence for operating the mobile application platform.

The platform companies normally charge a platform service fee to the drivers, while the drivers derive the actual transportation service income. In the past, as an information and technology service company, the platform service fees earned were typically taxed, for VAT purposes, as either a technology fee or commission income in practice.

However, that changed completely due to the issuance, on July 14 2016, of the Ministry of Transport's new Provisional Rules for Administration of the Operation and Service of Online Appointed Taxis. According to the provisional rules, online car sharing platform companies will assume the transportation contractor's (i.e. the driver's) liability, ensure ride safety, and guarantee the rights of the riders. While an explicit requirement for the platform to obtain an operating licence for road transportation was removed from the final version of the provisional rules (this was included in the earlier draft), the obligations placed on the platform company still raised the question of whether the platform company should be treated as a principal for ride supply, and whether the revenue derived should be classified as a transportation service income of the platform.

The classification of the revenue is critical from a VAT administration perspective, as it directly impacts the real tax burden of the taxpayer. The existing applicable VAT rate for both information and technology services and commission income is 6%. The applicable VAT rate for transportation services is 11%. The tax administration's classification of revenues is impacted by various factors. The Chinese tax guidance on revenue classification is quite limited, with itemised lists of service types set out in the guidance. For any type of income that is not specifically dealt with in the itemised list, the classification is very much left to the discretion of the in-charge tax authorities. These will typically make reference to the other related classifications, especially the accounting classification and the regulatory classification, for guidance.

As such, in the case of car sharing platform companies, as the industry regulator pushes the transportation-related responsibilities and obligations to the platform company, the tax authorities in turn have to assess whether the platform companies should be viewed as effectively operating as transportation companies. Consequently they need to evaluate whether the platform revenue should be classified as transportation service income for both industry regulatory and tax administration purposes. Different tax authorities in different parts of China can end up going in different directions on such revenue classification. As such, ultimately further State Administration of Taxation (SAT) guidance would usually be needed to ensure consistent outcomes. Even then, the business models may have moved on by the time the SAT gets around to this, which leaves a new open area requiring further guidance to be issued by the SAT. Therefore, more responsive and timely guidance from the SAT on these open issues is critical.

As more industry regulations are rolled out for new sectors such as vehicle-less transportation services (i.e. where a logistics company provides road transportation services without owning any of the trucks), and fintech, etc., there will be a similar need for a re-assessment of the existing tax treatments and how they align with new industry regulations.

Uncertainty on cloud service revenue classification

The National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) has set out the following definition of cloud computing: "Cloud computing is a model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g. networks, servers, storage, applications and services) that can be rapidly supplied and accessed with minimal management effort or service provider interaction".

Cloud service models are typically segmented into three categories:

Software as a Service (SaaS). The consumer is granted use of the provider's applications running on a cloud infrastructure;

Platform as a Service (PaaS). The consumer is granted the use of a suite of programming languages, libraries, services, and tools, operated over the cloud infrastructure; and

Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). The consumer is granted the use of processing, storage, networks, and other fundamental computing resources, allowing the consumer to run software, including operating systems and applications.

If we look at the cloud computing models from the existing/traditional tax administration perspective, the classification of the cloud service revenue largely depends on whether the assets or the rights associated with the assets are transferred to the consumer.

The provision of cloud services, like the provision of most digital economy services, does not require material human input. It mainly relies on the utilisation of the hardware and technology, and the services are often rendered on an automated basis (i.e. with minimum or even no involvement of manpower). The assets through which the services are rendered remain as the assets of the cloud service provider throughout the whole process. Ad hoc manpower inputs are merely for the purpose of maintaining the equipment and solving technical issues, rather than for the purpose of directly carrying out the service operations, per se. As such, the cloud service revenue may potentially fall into the classification of equipment leasing, or software licensing under traditional tax rules.

The existing Chinese tax regulations generally define services as those rendered by human beings. In practice, many tax authorities in China still treat cloud service income as either leasing income or licence fees, given the limited human service provision. Nevertheless, it might be argued that this does not reflect the true character of the cloud service model. This approach, in practice, may increase the tax burden on the overseas cloud service provider as corporate withholding tax may be imposed on the payment from the Chinese service recipients. Withholding tax would be imposed on the basis that this is passive income – this may be considered inappropriate given that service income derived by an overseas service provider should not be subject to China income tax, unless such income is attributed to a permanent establishment in China.

With the fast developing artificial intelligence (AI) and robotic process automation (RPA) technologies, it is an inevitable trend that more and more services will be rendered by machines instead of by human beings (or by both operating in an integrated fashion). Looking ahead, Chinese tax rules may need to evolve to consider the underlying economic substance of the transactions and arrangements, and lessen their fixation with formalities such as whether the provision of services is mainly asset-driven.

Practical challenges with the taxation of intangible property transfers

When an intangible property or a right associated with an intangible property is transferred to a customer, the question arises of whether the revenue derived from such transfer should be classified as a licensing fee or as sales income. Both involve the transfer of a right associated with the intangible property (e.g. ownership, copyright, etc.). Technically speaking, where there is a property transfer, the revenue classification will be assessed based on the intrinsic character of the right derived by the customer from the property transfer, and that assessment will be based on the review of the contractual evidence as well as the manner of settlement for the transaction. Controversy can arise in China in relation to software products. This is because software products do not have a single and exclusive tangible form. They could be easily transferred (i.e. no physical transportation is required) and duplicated with no restriction. Furthermore, given that software users will typically not purchase the software source code, there is a very blurred line between the purchase of software and the licence of the software. This makes the revenue classification very difficult in practice. It becomes even more challenging when it comes to the cross-border purchase of the licence of software, as both customs and foreign exchange regulations come into play as well.

Software licensing fees are subject to VAT at 6%, while the revenue from outright sale of software is subject to VAT at 17%. If the licence fee is paid to an overseas party, the Chinese licensee would need to withhold the VAT from the outbound payment. Licence fee payments made to overseas parties are also subject to corporate income tax withholding tax at 10% (subject to tax treaty relief). By contrast, inbound purchases of software are not subject to corporate income tax or withholding tax, and are only subject to VAT at 17%. A key distinction also arises in relation to the relevant taxing authorities: for the licence the tax will typically be administered by the tax authorities, for the software purchase (imported in physical form) the tax will typically be administered by the customs bureau.

With the enhancement of the internet data transmission speed, there is normally no longer a need for software to be physically transported from the seller to the buyer. Therefore, regardless of whether it is purchase or licensing of software, the Chinese customer can download the software directly from the internet. However, under the foreign exchange regime, where a purchase of software is in point, the Chinese customer would typically need to present a customs import document in order to remit the payment to the overseas seller. Unfortunately, there is no category of intangible product importation under the prevailing China customs regime.

This has led many companies, in practice, to either treat the purchase of software as a licensing arrangement, and withhold the 6% VAT rate and 10% withholding tax (unless reduced by a relevant tax treaty) accordingly, or, physically import a certain physical medium (e.g. CD, flash disk, etc.), declare the value of the medium to be that of the software, and pay 17% VAT accordingly. These practical issues may continue to exist for as long as the customs bureau, foreign exchange authority and the tax authority still separate the administration of software import versus licence.

The above are just a few examples of the challenges faced by the Chinese tax authorities when it comes to properly classifying revenue and applying the relevant tax treatments. With the ever-evolving new operating models in the digital economy, identifying the most appropriate tax classification will likely be a continuous process of exploration, education, and evolution pursued jointly by taxpayers and the Chinese tax authorities.

Issues with traditional tax administration mechanisms in the digital economy

The traditional tax administration approach in China relies heavily on the paper accounting records and vouchers of a taxpayer. Especially when it comes to the deduction of expenses, it is crucial that the taxpayer maintains traceable and verifiable proof in the form of official tax invoices (fapiao). These fapiao are so central to tax administration that bona fide expenses incurred during business operations will simply not be deductible unless there are fapiao to support them. This traditional system is less compatible with digital economy activity, and it can be extremely difficult for the Chinese tax authorities to verify the actual revenue and profits of a digital transaction, due to the following reasons:

Digital transaction records come in a wide variety of electronic forms and can be scattered across numerous different systems. They are easy to duplicate, delete, or modify, and can be extremely difficult to verify;

Speed, low cost and lack of geographic constraints are some of the key competitive advantages of the digital economy. Hence, many transactions are concluded without formal contracts, and between parties that are not registered with the tax authorities; and

Many transactions are with individual consumers, who do not seek tax deductions for their purchases and hence do not request formal tax invoices. This has limited the reach of the invoice system, which is one of the backbones of the Chinese tax administration system.

Especially for the vast number of individual customer-to-customer (C2C) sellers, given that they are often not registered either as a company (with the Administration of Industry and Commerce) or as a taxpayer (with the tax authorities), their online sales can occur in an information vacuum zone for tax administration purposes. The gap between traditional tax compliance requirements and tools and the manner of operation of businesses in the digital economy can lead to tax issues for both authorities and taxpayers, e.g. significant loss of tax revenues for the China tax authorities, or overpayment of taxes by taxpayers.

Challenges for the invoice-based tax administration environment

For digital economy companies that adopt the platform model, a continuing debate is whether their revenue will be recognised on a gross basis or on a net basis. That is, whether the income arising to traders/operators using the platform should first be considered as revenue of the platform, with a corresponding deduction reflecting the payment to the traders/operators. Under a perfect tax system, no matter which basis is adopted, those companies' actual VAT and corporate income tax (CIT) burdens should not be affected. This is because even if the companies recognise revenue on a gross basis, they should be able to take deductions and credit for the services rendered by those service providers registered on the platform. Unfortunately this may not hold true under the existing invoice-based tax administration regime in China.

The real income of the platform companies is the platform service fee or commission fee collected from the service provider or sometimes from the end customer. However, the service payment flows generally do not directly reflect this. Almost all third-party payment systems (e.g. AliPay, WeChat Pay, etc.) directly interface with the platform companies. The total goods/service proceeds paid by the end consumers are remitted into the account of the platform companies via the third-party payment systems. After deducting the applicable service fees or commission fees, the platform companies will then remit the balance to the account of the service providers or seller of goods. Further, based on the legal documents used by those platform companies (especially for O2O service companies), it can be left unclear whether they are holding themselves out as a platform provider or a master service provider. Some platform companies, for the purpose of building up their brand names, tend to package themselves as the provider of certain services. End consumers often ask the platform companies to issue invoices for the gross service fee. In practice, in many cases, platform companies may end up issuing such invoices as requested and recognise revenue on a gross basis, although this may not reflect the real business substance.

A further issue arises with expense accounting and deductions. To ensure fast growth, many O2O platforms adopt a relatively open policy in soliciting service providers onto their platforms. Almost any individual, after satisfying certain minimum requirements, can register as a service provider on the platform and provide services to the end customers. Those platform companies normally do not have sufficient resources to request (or monitor) that those individual service providers issue tax invoices, obtained from the tax authorities (smaller businesses in China may not have their own tax invoice printing equipment, but may obtain tax invoices from the tax authorities, for customers, on an 'as needed' basis). When the platform companies are required to recognise their revenue on a gross basis for tax purposes (e.g. the full amount paid by the end customer, rather than merely the platform service fee charged to the individual service providers), they are relying on deducting the service provider remuneration for tax offset. If the platform companies cannot obtain valid tax invoices from those service providers, in practice, the China tax authorities would deny the CIT deduction as well as VAT credit on such costs (even though they are bona fide service costs), which will significantly increase the CIT and VAT costs of these O2O platform companies.

In addition, many platforms and websites provide individual user incentives (in particular cash bonuses) in order to attract consumers and increase the click rate of the website. Individuals will not be issuing any invoices on the receipt of these cash bonuses, leading to tax issues. In particular it may be challenging to obtain a CIT deduction for the cost of the cash bonus. While we have seen cases where the tax authorities allowed taxpayers to take CIT deductions for such expenses based on the internal system log of incentives given (even though not substantiated with valid invoices), it is more common in practice that taxpayers would lose such deductions as a result of a 'lack of valid supporting documents'.

The above issues may be difficult to resolve under China's existing invoice-based tax administration system. With regards to ensuring collection of tax from the service providers operating through platforms, a mandatory withholding mechanism at the platform company level may be a quick solution although that may hinder the commercial development of China's SME sector, and slow China's economic digitisation more generally. But in the long-term, the change of the overall tax administration environment (i.e. from a paper based system to a technology oriented system) seems to be the ultimate solution. Fortunately, we are already seeing changes in China, such as the upgrade of the Golden Tax System, the rollout of electronic invoicing in e-commerce transactions, etc. The tax authorities are even exploring the use of blockchain technology in the tax administration system. As the tax administration system gains greater access to digital transaction data (from platforms and payment providers), and is in a better position to verify the completeness and accuracy of taxpayer submitted data, it may be possible to progressively resolve the tax administration issues above.

Individual income tax (IIT) issues

The popularisation of internet-based commercial activity provides opportunities to almost every individual to carry on business, whether on an ad hoc or more full-time systematic basis, via online C2C sales to O2O sharing services and much more. However, for individuals carrying on small scale business activity on an unincorporated basis, the existing, outdated IIT law provisions throw up various hurdles to appropriate taxation.

The issue may be illustrated with the example of an individual driver who offers O2O car sharing services. For such an individual driver, the leasing or depreciation expenses of his car, the gasoline expenses and the platform service charges normally account for more than 50% (sometimes even up to 70% or 80%) of the individual's total car sharing service income. According to the existing China IIT regulations, if such service income is treated as 'remuneration for personal services' for IIT purposes (this is one of several categories under which IIT can be imposed), the eligible expenses deduction cap is merely 20% of receipts, which is far below the real cost and expenses incurred by the individual driver. This leads to such a high IIT burden for the individual that it has caused many to seek ways to avoid paying IIT in the first instance.

It would be more appropriate to treat the individual driver as an unincorporated 'privately-owned business' for IIT purposes (a separate IIT taxing category). This would allow the taxable income of the individual to be calculated as the difference between the total service income and the actual costs/expenses/losses incurred for the provision of such services. But the tax administration cost involved in being recognised as an unincorporated 'privately owned business' for IIT purposes, and the technical knowledge required to manage this, are generally perceived as too high to be feasible by O2O car sharing drivers and other small business operators.

The existing IIT regime was enacted more than 20 years ago, and has been slated for replacement by the government, possibly in 2018. Before the revamp of the IIT Law, it is up to the taxpayers and the local tax authorities to negotiate for a more reasonable taxation method (e.g. deemed profit) on a case-by-case basis. Before a sustainable and practical solution can be achieved, we will likely continue to see a large population of such service providers not fully complying with their IIT obligations.

Tax enforcement in the digital economy

While there may be gaps between the existing Chinese tax regulations and what is needed for the digital economy, the Chinese tax authorities have been endeavouring to improve the tax administration environment, so as to provide a fair competitive environment for players in both the digital economy and the traditional economy.

Tax registration

Tax registration is the foundation of the taxing relationship between the tax authorities and taxpayers. Most of the existing large e-commerce platforms (e.g. Tmall, Joybuy, etc.) require the sellers who wish to set up their online stores on the platform to provide business licence and tax registration records. Individual sellers, privately owned businesses or any companies that do not have proper business and tax registrations are not permitted to set up online stores on those platforms. Yet, apart from these large e-commerce platforms, there are quite a lot of other smaller platforms that do not impose any registration requirement on the merchants. Further, some merchants use their own web domains to carry out business, and the domains may not even be registered under the actual merchants' names. This has made it extremely difficult for the tax authorities to enforce tax collection, leading not only to loss of tax revenue, but also to a competitive disadvantage for those merchants who have duly registered and paid their fair share of taxes.

The Chinese tax authorities are aware of this and in the draft revised China Tax Collection and Administration Law, it is stipulated that a taxpayer who conducts online business must disclose its tax registration information prominently on the homepage of its website or the homepage on which the business activities are carried out. It also requires all e-commerce platforms to report trader activity to the tax authorities. The requirement for financial institutions to report sizable transactions automatically to the tax authorities may also provide matching information to track and tax e-commerce activity. In the long run, this should lead to a more equal and level playing field for all businesses.

Digitisation of invoices

In the digital economy context, as all contracts, orders and vouchers for internet transactions and services are kept in the form of electronic records or digital data, no paper invoice will be involved. Electronic records may be easily modified without leaving any traces. As a result, the tax authority is losing its most powerful and direct tool (i.e. the paper invoice) in tax collection and administration.

In response to such trends, the Chinese tax authorities have been rolling out the electronic invoice reform across China since 2016. In contrast to traditional paper invoices, electronic invoices cover the whole invoice administration process, which helps to provide reliable and traceable evidence for tax administration and collection, yet is easier and less costly to implement.

Certainly, challenges posed by the non-registration issue mentioned above as well as the 'no-invoice' ecosphere in many thin margin and less value adding industries still exist, and probably will not be resolved until the tax administration system is able to either effectively access and collect digital transaction data, or verify the completeness and accuracy of taxpayer submitted data.

Innovative enforcement measures adopted by other countries

A variety of innovative measures, leveraging new technologies and directed at digital economy tax challenges, have been adopted by other countries in recent years. These may also be indicative of the direction the Chinese tax administration could look to move in coming years:

Use of blockchain to deal with the use of false identities and ensure effective registration and authentication of taxpayers;

Blockchain use for security and reliability of sales/transaction records, e.g. for dealing with 'sales suppression' and other manipulation of accounting records relevant to tax;

Linking regulatory requirements to tax compliance – e.g. obtaining a building permit for the second stage of a construction project may be made dependent on having uploaded all invoices/payments for the first stage of the project to the taxpayer's personal tax account on the tax authority website;

Obligatory electronic invoicing and instantaneous transfer of all sales data to the tax authorities;

Obliging online platforms to mark down the 'ratings' of traders on their platforms that do not provide electronic invoices, or excluding them from selling goods through the platform altogether; and

Tax authorities could seek to work with platforms to determine what data the platforms could give them in bulk aggregated form, which would be useful for compliance efforts but which would not put an excessive burden on the platforms.

Advice to taxpayers

For companies operating in the digital economy, it can be very confusing and frustrating when faced with all the uncertainties and even seemingly unreasonable tax burdens. While the Chinese tax authorities at different levels are actively conducting their own studies and research to seek solutions to the existing issues, with all the new and evolving business models emerging and new issues surfacing every day, this is an uphill struggle.

To thrive in the digital economy and to stay tax compliant while avoiding excessive tax costs, companies may wish to consider the following:

The company should review its operating model and supply chain so that business sustainability is built on commercial strengths, rather than on temporary advantages that exist merely because of a lag in the adaptation of the tax administration system to the digital economy.

To potentially obtain a more reasonable tax treatment, companies may be better off proactively approaching the tax authorities, explaining their seemingly complex transactions, quoting the relevant tax framework, and drawing analogies to existing tax positions and treatments, in order to reach consensus with the tax authorities on the tax position. Given increasing tax compliance and anti-avoidance enforcement efforts, if the taxpayer and the tax authority each operate in their own silo, the lack of transparency and communication may simply lead to more uncertainties, and unsatisfactory outcomes.

Sunny Leung |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China 26th Floor, Plaza 66 Tower II 1266 Nanjing West Road Shanghai 200040, China Tel: +86 21 2212 3488 Sunny Leung is KPMG China's national technology, media and telecommunications (TMT) sector tax leader. She has assisted various local tax authorities to perform studies on common China tax issues that have emerged in the new digital economy, possible solutions, and the potential impact of BEPS. Sunny has been extensively involved in advising clients on setting up operations in China, M&A transactions, and cross-border supply chain planning. She has been providing China tax advisory and compliance services to domestic and multi-national companies in the TMT, as well as traditional manufacturing and service industries. Sunny has also been providing tax due diligence and tax health check services in China. |

Benjamin Lu |

|

|---|---|

|

Director, Tax KPMG China 26th Floor, Plaza 66 Tower II 1266 Nanjing West Road Shanghai 200040, China Tel: +86 (21) 2212 3462 Benjamin Lu has provided tax advisory and compliance services to a variety of clients relating to company setup, optimisation of transaction models, tax compliance and continuing operations, and has provided both tax due diligence and tax structuring advice on M&A and group restructuring transactions. Benjamin has rendered tax services to both multinational clients as well as domestic clients, and has an insightful view of the needs of the clients as well as China's tax regime and its practices. Benjamin has extensive experience in a wide range of industries including technology, media and telecommunications (TMT) (including digital economy, technology, media, etc.), consulting, industrial markets (including semi-conductor, chemical, automotive, etc.) and consumer markets. |

Jessie Zhang |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China 8th Floor, KPMG Tower Oriental Plaza, No. 1 East Chang An Ave., Beijing, China Tel: +8610 8508 7625 Jessie Zhang is the northern China tax leader for the telecommunication, media and technology sector and has abundant experience in serving technology start-up companies in China. Jessie's experience covers a wide range of assistance, including pre-acquisition tax due diligence, entry strategy and operation structuring, pre-IPO restructuring and compliance review. She specialises in advising on China tax incentives including research and development (R&D) super deduction, R&D management optimisation and group incentive planning, high and new technology enterprises, government cash grants, and so on. |

Grace Luo |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China 21 Floor, CTF Finance Center 6 Zhujiang East Road, Zhujiang New Town Guangzhou 510620, China Tel: +86 20 3813 8609 Grace Luo graduated from Sun-Yat Sen University in 2001 with a major in finance and taxation, and she joined the tax department of the KPMG Guangzhou office in the same year. She has been providing tax advisory and transfer pricing services for 16 years. Grace has been actively involved in providing tax efficiency planning, corporate restructuring, tax review and tax risk management advisory services to multinational and domestic clients. She has rich experience in assisting clients in communicating with tax authorities. In addition, she has abundant experience in various transfer pricing projects, including multinational and domestic transfer pricing audit and planning advisory. Grace is also a key member of KPMG's Centre of Excellence for indirect tax advisory services, which was established to cater to the Chinese VAT reform. So far, she has been involved in many domestic and multinational companies' VAT reform projects, including financial impact analysis, contract review, and advisory services on preparation and implementation for the VAT reform. Grace's clients cover a wide range of industries, including finance, automobiles, consumer market and retail, real estate, manufacturing and services, etc. Grace is a frequent speaker at public seminars held by KPMG. She is often invited as a speaker in seminars held by industry associations and educational institutions, as well as technical discussion interflows with China tax authorities. |