The challenge of assessing unique contributions in modern TP

One key development in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines (OECD TP Guidelines) – and consequently in many national tax rules – has been the introduction of new rules on ‘intangibles’.

Intangibles are loosely defined as anything that is (i) neither a physical nor a financial asset; (ii) used commercially in a way that third parties would likely remunerate, and (iii) that in some way can be owned or controlled. Per the regulations, taxpayers must reflect these intangibles in their transfer pricing (TP) setup and in particular need to consider which entities contribute to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection, and exploitation of these intangibles (so-called DEMPE functions).

These new rules affect a large number of multinational enterprises who rely on various unique and valuable intangibles to set themselves apart from their competitors. Brands, patents, know-how and similar items typically are key value drivers precisely of those international companies that are successful internationally. Moreover, these intangibles are often created by various entities who conduct various development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation (DEMPE) functions. Overall, the effect is that various different entities are in some way involved in the core joint value creation and taxpayers must reflect this in their TP.

While the OECD and further tax rules are quite explicit in that these factors need to be taken into account in the TP setup and documentation, there is unfortunately no specific guidance in the regulations that would indicate precisely how these factors should be reflected. Thus, practitioners will need to rely on economic methods to find a reasonable and defensive setup.

Several different methods can be applied, but in practice there are several challenges: Observable third-party market transactions, such as the licensing of comparable brands are rare and comparability is often somewhat questionable, precisely because the taxpayer’s intangibles are unique. Cost-based methods to reflect different contributions by each party are somewhat objective as they are measurable, but often costs may be a poor measure of ultimate contributions to success, especially when different categories are compared. Industrial economics provide practical solutions to isolate and quantify individual contributions to joint value creation based on internal company data.

Application to the tech industry

The tech industry in particular is characterised by business models where technology platform, brand attraction for users and data exploitation from active user profile intermingle to develop and monetise digital models. This no longer only applies to the pioneering giants like Google and Facebook, but to an ever-growing number of tech companies whose business models have been boosted by COVID-19.

In case key intangible contributions arise from different group companies, the determination of relative value contributions through cooperative game theoretical analysis is particularly suitable when the parties negotiate the economically fair sharing of a conjointly generated profit in the tech industry. A fair allocation of profits is consistent with the OECD arm’s-length standard, and in many arm’s-length situations where independent parties accepted joint profit sharing, the Shapley value has been considered a fair allocation key. One solution outcome of cooperative game theory, it measures the average marginal profit generated by a party through its intangible contributions relative to the marginal intangible contributions of the other parties.

The great advantage of applying Shapley value in the tech industry is that it can be based on the evaluation of internally available big data whose economic value can be assessed by the data analytics specialist of the respective multinational enterprise (MNE).

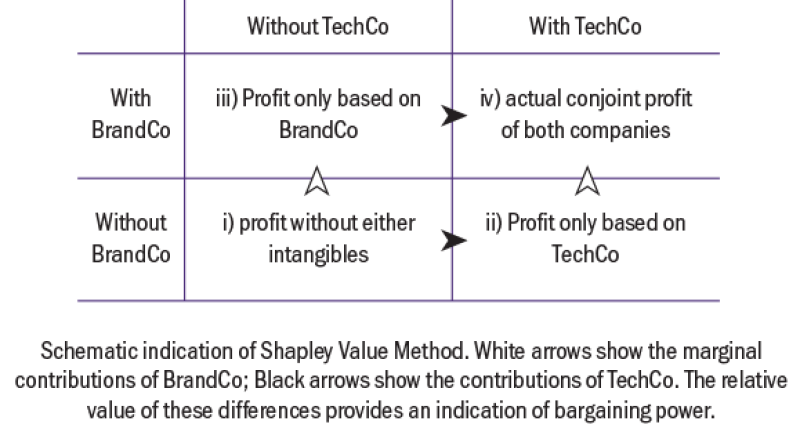

Let us consider a simplified example of a company with a strong platform technology, owned by TechCo, that is marketed under a strong brand owned by BrandCo. For simplicity, we assume the user base data is also monitored and exploited by BrandCo. Under Shapley value, this means four scenarios are analysed:

(i) The entrepreneurial profit that would be generated by both companies without the intangible contribution (this is usually 0);

(ii) The profit that the TechCo would generate without the Intangible contribution of the BrandCo;

(iii) The profit that the BrandCo would generate without the TechCo's Intangible contribution; and

(iv) The profit that both companies generate jointly by using both intangibles (i.e. the profit actually generated).

The relative value contribution according to the Shapley value concept results from the comparison of the profits with and without the participation of the respective company in these scenarios. For example, if one company were already able to generate relatively high profits on its own, while the other company would only generate relatively low profits on its own, it would be expected that the first company would be able to assert greater bargaining power in negotiations in a third-party situation. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

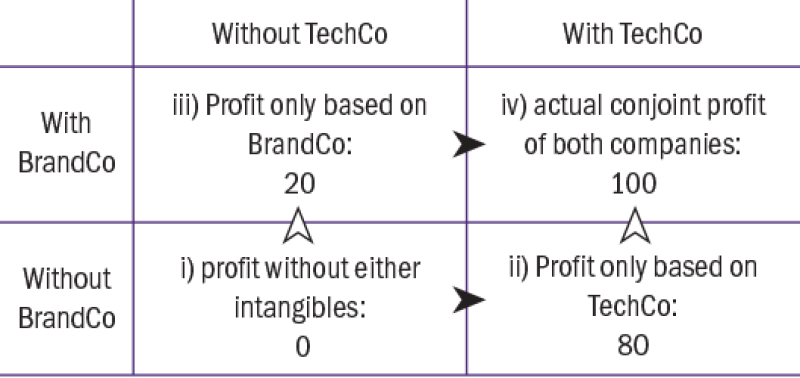

The application of the Shapley value analysis requires a precise differentiation of the scenarios described and the profit that can be achieved in each case. In our illustrative tech example, assume the MNE has a busines model where it monetises having users engaging on its technology platform being accessed by external third-party advertisers.

If one compares the full brand contribution with the full technology contribution in a simplified Shapley value analysis, it can be seen that both BrandCo and TechCo could not generate any entrepreneurial profits on a stand-alone basis. A technical platform is worthless without a brand to market it because there is no target group for advertisements.

Conversely, a brand without a technology platform product is also worthless, as there is no way to commercialise and monetise the brand purely abstractly. Brand and technology are therefore not only integrated with one another, but are completely dependent on one another; the company's profit only arises from the interaction of both intangibles.

Since both parties are completely dependent on each other from this point of view, there is also no indication that either of the parties would have a stronger position when negotiating between unrelated third parties; the Shapley value analysis would accordingly attribute half of the profits to brand and technology owners respectively.

In real life, the intangible contribution can be assessed more precisely. Not all parts of the technology are to be valued equally as ‘unique and valuable’ intangibles. In particular, the basic technical aspects of the product can be technically relatively easy to replicate and many competitors regularly copy technical features from one another. It can therefore be questioned whether the entire technology can actually be ‘controlled’ or ‘owned’. Even if technology patents are subject to a certain degree of protection, the main features can often be replicated with comparable results.

However, not all technical components can be easily copied. In the example, the technology contributor might own some specifically proprietary technology that gives rise to higher value and is not easy to copy. On this basis, the technology can basically be divided into two elements (i) replicable technology; and (ii) proprietary technology.

The brand also comprises (i) relatively simple, replicable brand images, such as the pure registration of a general brand name, but also (ii) the particularly valuable consumer associations, i.e. the long-term willingness of consumer to pay a brand premium – especially for technologically superior products.

The differentiation of the intangibles enables a data-based application of the Shapley value method. In particular, it is possible to create a simulation of sales and profits if the difference between the 'simple' and the more valuable intangibles in both categories is taken into account. In analogy to the situations considered above, the following scenarios result in the Shapley value analysis:

(i) If both BrandCo and TechCo only contribute basic data and technologies), there will be no entrepreneurial profit since no marketing opportunities and thus no uniquely attractive business model can arise. In fact, the combination of 'basic data' and 'replicable technology' would not result in any significant entrepreneurial profit: Without the more valuable aspects of the intangibles, only rudimentary business could be pursued, and the busines model would not be attractive. A simulation of the income shows that the expected sales just absorb total costs. This fact demonstrates that the simpler aspects of the intangibles are actually of low value.

(ii) The TechCo alone could fall back on the proprietary technology, while for regulatory reasons exploiting just the baseline and not the most valuable information provided by users attracted by the valuable brand. A simulation of the profits by the group's data analytics team shows that the company would not achieve the actual profit, but could still achieve around 85% of the actual profits.

(iii) The BrandCo alone would like full exploitation of all aspects of available user base, but could not use the proprietary technology to be able to achieve extra profits. The data analytics team assesses that the BrandCo would be able to achieve around 10% of the actual result.

(iv) Both companies can jointly use the proprietary technology as well as access to the most valuable data. Since this corresponds to the actual situation, the joint profit in this constellation is the actually earned profit.

Overall, the picture emerges in which both companies could generate a profit for themselves, but achieve additional profit from the joint cooperation. Nevertheless, it is noticeable that the contribution of the TechCo is to be assessed as higher, as it would both generate a high hypothetical profit on its own and is also able to commercialise the valuable brand aspects much better than the BrandCo alone can.

The Shapley value analysis compares the marginal contributions of the intangibles: For the brand there is an increase in profit from 0 to 10 (without the TechCo contributions) or from 70 to 100 (with TechCo), i.e. a total limit contribution of on average 20; For the technology there is an increase in profit from 0 to 70 (without the contributions from the BrandCo) or from 10 to 100 (with the contributions from the BrandCo), i.e. an average increase of 80. Overall, in this case, the basis of the relative limit contributions a division of the total profit of 20:80 in favour of TechCo.

Figure 2

Summary

The Shapley value method can be a powerful tool to calculate arm’s-length profits shares of highly integrated business models, in particular when multiple entities own interconnected intangibles for which no outside data is easily available. Its application is mathematically straightforward, but does rely on identifying appropriate profits in various different scenarios.

Although demonstrated specifically for the digital industry in this article, the method can generally be applied to various scenarios and industries and provide a practical way to meet the new TP challenges surrounding intangibles.

Yves Hervé |

|

|---|---|

|

Managing partner NERA Economic Consulting T: +49 69 710 447 508 Yves Hervé is a managing director in NERA's global TP practice and is operating in NERA's Frankfurt office. During the course of his professional career, Yves has covered all major TP consulting issues for global clients, from integrated value chain structuring and TP planning to global TP compliance issues and documentation, TP economic solution design, IP valuation, cost contribution solutions, business restructurings, tax audit defense and dispute resolution. Yves has a PhD in economics from the University of Saarland, Germany. |

Philip de Homont |

|

|---|---|

|

Director NERA Economic Consulting T: +49 69 710 447 502 Philip de Homont is a director at NERA. He is an expert in TP and intellectual property valuation. Philip specialises in TP litigation support for international corporations and law firms. His passion is to prepare clear and concise reports for complex cases based on rigorous analysis. He has extensive experience in defending licensing and valuation arrangements for intangibles.

Philip has a master’s degree in economics from the University of Warwick. |