Among the latest challenges facing the automotive industry is the impact of reciprocal tariffs on imports introduced under the current US administration. Specifically affected by this tariff regime are European and Asian manufacturers, which have to carefully (re)consider their business and operating model for the US market.

A tariff is a tax on goods that are brought into a country from abroad, making imported products – such as cars – more expensive (see IncoDocs’ What Are Reciprocal Tariffs and Why Do They Matter in 2025?). Tariffs have a significant impact on trade volumes and the profit margins of multinational enterprises (MNEs). As producers would usually pass on the added costs to consumers, prices are expected to rise, potentially decreasing demand.

However, the automotive industry is already facing margin compression across global markets, which is due to several trends, such as cost pressures, shifting consumer preferences, and rising competition (see Deloitte’s 2025 Global Automotive Consumer Study).

With fierce competition in place, producers cannot easily pass on additional costs from tariffs. This can have a devastating effect on already shrinking margins, depending on how long trade tensions continue, calling for short- or long-term measures from MNEs to protect their business models. According to analysis by Bain & Company, original equipment manufacturers in the automotive industry had average profit margins of just 5.4% in Q1 2025, which represents a more than 40% drop from their peak in 2021.

This article uses an example of an MNE to outline a structured approach to mitigate the impact of tariffs through short- and long-term transfer pricing (TP) strategies. It also explores how the feasibility and effectiveness of these strategies depend on the ability to pass on costs to end customers.

TP strategies in response to tariffs: a two-stage approach for MNEs

In an era of escalating trade tensions and rising protectionism, MNEs face increasing pressure to adapt their TP models. Tariffs – especially those imposed on intragroup cross-border transactions – can significantly erode profit margins, particularly when market conditions prevent companies from passing on additional costs to customers.

A key factor in determining the impact of tariffs on pricing strategies is the concept of price elasticity of demand.

In markets where demand is inelastic, consumers are less sensitive to price increases, allowing companies to pass on the cost of tariffs without significantly affecting sales volumes. This may sometimes be the case for premium automotive brands or essential vehicle components.

Conversely, in markets with elastic demand, even small price increases can lead to substantial drops in sales, making it difficult to shift the tariff burden to customers. In such cases, companies may need to absorb the cost themselves or adjust their TP models to maintain competitiveness and compliance.

As a consequence, while most MNEs have started to review their TP policies, deeply analysing price elasticity is key in evaluating the options.

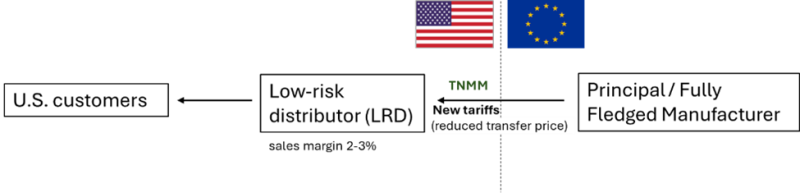

Baseline scenario: European principal and US low-risk distributor

Let us consider a common TP structure where a European principal sells finished goods in the form of ready-to-sell automobiles to a related-party low-risk distributor (LRD) in the US. The LRD pays import duties and sells the goods to US customers. The LRD earns an illustrative routine margin of 2–3% on sales, determined using the transactional net margin method (TNMM). With the imposition of new tariffs – for example, 25% on industrial goods – the LRD’s cost base increases. If the LRD cannot pass on these costs to customers due to competitive pressure, its margin may fall below the arm’s-length range (ceteris paribus), triggering TP compliance risks.

This is just one standard situation many automotive companies now find themselves in. There are surely a lot more constellations of intercompany relationships and many of these will add to the complexity of the situation. Regardless of the current TP model, however, every MNE will be confronted with the question of how to respond to new tariff schemes.

Among the available measures, some can be used easily and at short notice, while others might only be available with higher opportunity costs and therefore only make sense in the long term. Presented below are possible short-term and long-term measures from a TP perspective and how effective they are as a response to tariffs.

Short-term strategy: adjusting the transfer price

The objective of the short-term strategy is to preserve the LRD’s arm’s-length margin and reduce the dutiable base. This can be achieved by reducing the transfer price from the principal to the LRD, which lowers the customs value and mitigates the tariff burden.

The following table illustrates the potential effect of new tariffs on the profit distribution between the principal company and LRD depending on whether short-term measures are taken.

Metric | Pre-tariff | Post-tariff (no transfer price change) | Post-tariff (transfer price adjusted) |

Transfer price | 100 | 100 | 85 |

Tariff rate | 0% | 25% | 25% |

Tariff paid | 0 | 25 | 21.25 |

LRD margin | 2–3% | -2% | 2–3% |

Principal profit | Residual, currently around 6% | Reduced, due to lower demand | Further reduced, due to lower demand and transfer price |

As a result, the LRD may be able to achieve again an operating profit margin that can be benchmarked against unrelated third-party profit levels. This approach maintains TP compliance and reduces customs duties. It may also stimulate demand due to stable end prices.

However, in this scenario the principal absorbs the margin loss, and customs authorities may scrutinise price changes. As a first measure, MNEs should carefully review their function and risk profiles and establish which of the parties involved in a transaction has to bear the additional customs burden. The control over risk concept gives valuable guidance in doing so. As a general rule, however, robust documentation is required.

In the US, this could involve a requirement for Customs and Border Protection reconciliation. This is a compliance mechanism under Title 19, Section 1401a of the US Code that allows importers to declare provisional values for goods at the time of entry and adjust them later, typically due to TP adjustments or other post-importation changes.

Another important consideration is the classification of goods transactions for customs purposes. Often, the invoice price of imported goods includes bundled components such as services, intellectual property (IP) rights, and/or management fees.

However, not all of these components are subject to (increased) customs duties. For example, services that are not directly related to the production or sale of the goods may be considered non-dutiable. Therefore, it is crucial to delineate the dutiable and non-dutiable elements of the transaction value. This process, known as debundling, helps to ensure that only the appropriate portion of the transaction is subject to tariffs, potentially reducing the overall duty burden.

To summarise, short-term measures from a TP perspective can help to achieve compliance but may not limit the overall burden of newly imposed tariffs. What can help at short notice is a review of the master data used for customs declarations and adjusting the classification of imported goods to avoid unnecessary overpaying of duties. The next section will analyse whether long-term measures have a different depth and can bring more relief.

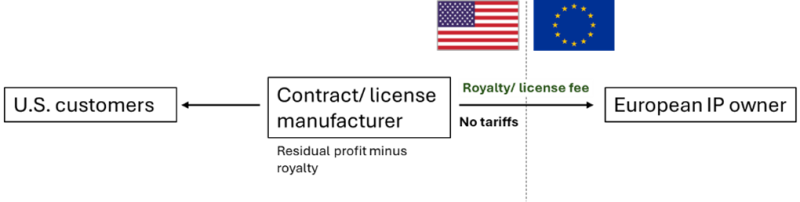

Long-term strategy: restructuring the supply chain

The objective of the long-term strategy is to eliminate or reduce tariff exposure. In this regard, over the long term, MNEs have the opportunity to strategically adapt their supply chains. One effective approach involves relocating the manufacturing function by expanding production operations within the US, as manufacturing goods locally allows companies to avoid import tariffs. Another option is to establish a US-based contract or licence manufacturer where the US entity manufactures locally and sells to customers, paying a royalty or licence fee to the European IP owner. An alternative is a hybrid model under which manufacturing is partially in the US and partially abroad, using a dual TP model such as cost plus for manufacturing and the comparable uncontrolled price method for licensing.

This strategy avoids (new) tariffs on finished goods, and royalty payments are often not dutiable. It may further align with broader supply chain resilience goals. However, it involves high upfront investment, and potential exit tax and business restructuring implications, and requires careful planning of IP ownership, contractual terms, and customs valuation.

The right strategy in the long term may also depend on the ability to pass on additional costs from new tariffs to customers. A complete shift in the supply chain may not always be the best solution. The following matrix outlines the TP strategies based on the ability to pass on tariffs and demonstrates the trade-off every MNE may face in this regard.

Customer price flexibility | Short-term TP strategy | Long-term TP strategy | Other considerations |

Cannot pass on tariffs | Lower transfer price to preserve LRD margin | Shift manufacturing to US; licence model | Potential exit tax for principal, shift in profit allocation |

Can partially pass on | Moderate price adjustment plus TP adjustment | Hybrid model: partial onshoring, partial licensing | Still decrease in overall (residual) profit margins, adds complexity to TP system |

Can fully pass on | No TP change needed | Maintain current model; monitor market dynamics | Margin monitoring and TP adjustment still needed as sales and cost of goods sold increase on LRD level |

If not all goods are ultimately sold in the US, companies may be able to take advantage of additional customs relief mechanisms such as duty drawback programmes, which allow for the recovery of duties paid on imported goods that are later exported.

Another potential strategy could involve splitting production between a US entity and a manufacturing site located in a low-tariff jurisdiction, thereby balancing cost efficiency with tariff exposure.

Additionally, companies may consider the use of bonded warehouses or free trade zones, which are designated facilities that allow for the deferral of import duties until goods formally enter US commerce. If the goods are re-exported or destroyed while in these zones, no duties are applied, making this a particularly effective strategy for products that are not intended for the US market. This highlights the importance of adjusting the strategies based on the different entities and transactions.

Key takeaways on TP strategy in relation to tariffs

Tariffs are more than just a trade policy tool – they are a catalyst for rethinking global value chains and TP models. Depending on the duration and severability of tariff schemes, MNEs can adopt a two-stage approach: short-term adjustments to transfer prices to preserve compliance and reduce tariff exposure, followed by long-term structural changes such as onshoring, licensing, or hybrid models to build resilience and optimise tax and customs outcomes.

The following table summarises the key characteristics of different TP set-ups for short-term and long-term measures.

Metric | Short-term set-up | Long-term set-up |

Import tariff exposure | High | None or low |

Manufacturing location | Europe | US |

TP model | Buy-sell (TNMM) | Licence + cost plus |

Royalty payments | No | Yes |

Customs duties | On full value | On raw materials only |

Principal profit | Reduced | Further reduced |

This article also highlights that TP considerations are not the only measures MNEs have available. Companies should conduct a thorough review of their master data and ensure they make accurate customs declarations, which can minimise the risk of overpaying duties. This includes verifying the correct classification of goods under the Harmonized System codes, confirming the country of origin, and ensuring that the declared transaction values align with TP and customs requirements. A well-maintained master data system not only facilitates compliance but also enables more effective use of customs planning tools such as the first sale rule or duty drawback programmes.

The right strategy depends on the ability to pass on costs, market dynamics, and operational flexibility. By aligning TP policies with customs regulations and evolving trade realities, MNEs can not only mitigate risks but also unlock new opportunities for value creation.

Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (DTTL), its global network of member firms, and their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte organization”). DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) and each of its member firms and related entities are legally separate and independent entities, which cannot obligate or bind each other in respect of third parties. DTTL and each DTTL member firm and related entity is liable only for its own acts and omissions, and not those of each other. DTTL does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about to learn more.

This communication contains general information only, and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (DTTL), its global network of member firms or their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte organization”) is, by means of this communication, rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your finances or your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser.

No representations, warranties or undertakings (express or implied) are given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information in this communication, and none of DTTL, its member firms, related entities, employees or agents shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage whatsoever arising directly or indirectly in connection with any person relying on this communication. DTTL and each of its member firms, and their related entities, are legally separate and independent entities.

© 2025. For information, contact Deloitte Global.