The shift towards the digital economy catalysed by the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the importance of intangibles in supply and value chains in all industries. For example, intangible assets (IP) account for 90% of S&P 500 companies’ assets according to an Ocean Tomo Intangible Asset Market Value Study in January 2021.

The economic benefit that IP can provide has paved the way for IP to play an important role in creating customer and shareholder value.

Financial services firms are prioritising IP investment that can drive economic benefit and firms’ value. This article frames IP transfer pricing in the financial services industry, with specific reference to the insurance industry. This framing is important, because insurers’ IP strategy and investment disrupts value chain and transfer pricing policies.

Framing IP transfer pricing

We start by framing some key transfer pricing parameters that define how multinational corporations (MNCs) and tax administrators evaluate, price, and adjust the transfer pricing for valuable IP, which will then be applied to two insurance examples.

The 2022 OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations (the ‘OECD Guidelines’) define IP as something that is not a physical asset or a financial asset and that is capable of being owned or controlled for use in commercial activities, and whose use or transfer would be compensated if it occurred in a transaction between independent parties in comparable circumstances. Therefore, from a transfer pricing perspective, intangibles may not necessarily be recognised as assets for accounting purposes.

The transfer pricing definition of IP is broader than the legal definition of intellectual property. Additionally, the legal ownership or funding of IP alone is not determinative of the entity that earns the majority of the returns on valuable IP. The returns on valuable IP are also shared across related parties that perform development, enhancement, management, protection, and exploitation (DEMPE) functions. Amongst related parties, returns range from stable cost plus/operating margins (low risk, low return) to revenue or profit/loss shares (higher risk, higher return or loss).

What, then, is ‘valuable IP’, to which the broad parameters noted above apply. The OECD Guidelines define unique and valuable IP as IP that is not comparable to IP used by, or available to, parties to potentially comparable transactions, and whose use in business operation is expected to yield greater economic benefits than would be expected in the absence of the IP.

With this OECD-based framing of IP, two insurance cases will be examined, one involving value of brand (marketing IP) and one involving digitalisation technology IP.

Revisiting insurance brand IP

Insurers are entrusted with helping policyholders to cope with, and recover from, some of the policymakers’ most challenging situations and this requires trust, competency, and assurance. A brand may embody and convey these attributes, and brands are important insurers.

Generally, the threshold questions are how important is a brand to an insurer and is the trust driven by the brand or actual/perceived financial strength, and/or is the brand a key differentiating factor influencing a customer’s choices and preferences?

Tax administrators in some countries have argued that insurance brands are unique and provide economic benefits that warrant returns in line with the higher risk, higher returns of valuable IP. For example, in India and other countries, if a local related party of a foreign parent company is incurring high advertising, marketing, and promotion expense compared with its peers, the tax examiners allege that the local related party is developing the brand.

In these situations, tax examiners have been known to impute transfer pricing adjustment based on the presumption that the local related party provides brand-related services to the legal owner of the brand.

The transfer pricing challenge is demonstrating that a particular insurance brand is, or is not, a high-value IP, particularly to tax administrations, and the opportunity is better aligned to brand cost and/or brand value with how and where the brand is developed, enhanced, funded, used, and exploited.

Some of the commonly observed transfer pricing methods deployed to price the use of insurance brands by related parties are as follows.

Allocations of cost of the relevant internal advertising, promotion, and marketing functions as part of cost-plus services charges to beneficiaries of centralised services (the ‘service charge model’);

Allocation of large third-party co-branding and third-party advertising cost, resulting in a de facto sharing of certain brand expense (the ‘cost allocation model’); and

Payments measured as a percentage of the relevant premiums and revenues determined with reference to marketing IP valuations and/or third-party royalty rates (the ‘royalty model’).

At the core of the difference in TP methods is a cost versus premium/revenue-based return on brand expense, and each insurer’s centralisation of DEMPE decision-making functions and position on the competitive advantage of the brand at the local market level are key determinatives.

The service charge model often involves the centralisation of key decisions related to DEMPE functions and the centralisation of brand-related expenses. When facing this in an examination, tax administrators may imply that the service charge model in general is not meant to cover high-value IP. Taxpayers in global and/or regional headquarters locations would be wise to proactively assess whether their use of the service charge model aligns with the management’s brand strategy and funding of brand development/enhancement, and the location of the DEMPE decision making.

Under the cost allocation model, if the third-party cost allocations are paired with a service charge model, the overall implications are similar to those described with the service charge model. If only third-party cost allocations are made, the taxpayer should pay careful attention to whether internal cost is largely decentralised internal cost with limited centralised internal cost. If this is not the case, there may be a gap in an existing service charge model with respect to the centralised internal cost.

The royalty model is premised on an argument that the brand provides competitive advantages and that the return on the brand expense should fluctuate with premiums/other related revenues. Where brand DEMPE decision-making functions have been centralised and significant brand expense has been centralised and/or a business or a brand has been acquired, there may be a strong case for applying the royalty model. Some key considerations for this are the level of brand recognition in the local markets and the balance of central versus local brand-related spending.

Insurance technology IP in the digital age

In the digital age, growth in the insurance industry is in part due to the growing adoption of the internet of things (IoT), a shift of insurers’ focus from product-based strategies to customer-centric strategies, and increased awareness among insurers to digitalise channels for acquiring products. According to The Deloitte Center for Financial Services 2022 Insurance Outlook Survey, more than 70% of respondents expect an increase in technology spending on artificial intelligence (AI), cloud computing and storage, and data privacy.

This technology, being deployed on digital platforms and through robo-advisors, is intended to augment or disrupt the market.

A digital insurance platform drives traditional business processes towards digital processes and empowers insurers by providing the efficiency of central-core systems and differentiating customer experience. Digital insurance platforms are expected to grow from $78.47 billion in 2017 to $164.13 billion by 2023, at a compound annual growth rate of 13.7%, according to a study conducted by Marketsandmarkets.

AI-enabled robo-advisors address everything from simple queries in an automated manner to increasingly sophisticated algorithms to automate advice or financial risk management processes. Robo-advisor IP may be particularly valuable from a product development, customer preference, or risk management perspective.

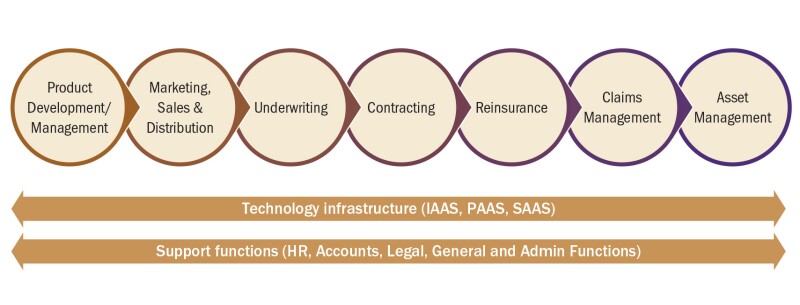

Two examples of how the digitalisation of the insurance industry is disrupting the typical insurance industry value chain are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Infrastructure as a service (IaaS), platform as a service (PaaS) and software as a service (SaaS)

In a typical insurance value chain, the role of technology was limited to providing the IT infrastructure for undertaking the insurance business prior to digitalisation. The two examples of digitalisation technology IP are value chain disruptors that lead to two important transfer pricing questions.

First: how important is digitalisation technology IP versus the key decision making of the business personnel prior to digitalisation?

The importance of understanding the business strategy underlying digitalisation technology IP cannot be understated. As has been the case with platform technology development and its use in other industries, the usefulness and capabilities of digitalisation technology IP are often expected to be exponential; that is, an increase over successive generations and an increase in commercial adaptation of the technology.

Over time, more business risk-taking decisions previously made by humans may be made by, and/or augmented with, technology. To get a snapshot of what this looks like and to track how it evolves over time, it is important to:

Understand the digitalisation strategy, particularly from a regulatory, commercial, and risk management perspective;

Understand who the key decision makers are with respect to digital strategy, funding, development, and enhancement;

Examine digitalisation of the customer experience from a technology as well as a marketing perspective; and

Identify and begin to track development budgets, cost accounting, milestones, and performance indicators.

The challenge is to begin tracking the development project, how projects impact human-centric processes and decision making, and how the benefit of the technology is measured. The emphasis here is on information that can help you properly delineate the valuable IP and identify the location of DEMPE decision making.

Second: how can DEMPE decision making and DEMPE functions be framed for transfer pricing planning or risk management?

With the digitalisation that allows for innovative working models adopted by MNCs, DEMPE decision making and functions may be performed in multiple locations.

From a transfer pricing perspective, IP returns and losses should align with DEMPE decision making and bearing the financial risk associated with the IP. If multiple related parties make DEMPE decisions and bear financial risk, the OECD Guidelines recommend risk be allocated to the related party exercising the most control over risk. This guidance must be balanced against tax examiners’ inclination to question the appropriateness of splitting profit or loss amongst the related parties involved in the DEMPE decision making.

If an insurer wants to centralise legal and economic ownership of digital technology IP, it is important to be able to demonstrate that arrangements amongst related parties are within the following parameters.

Limit DEMPE decision making to one or a very limited number of related parties with the right talent, experience, and insight across the MNC’s locations, products, and markets;

Ensure the DEMPE decision-making locations start out with, and continue to possess, the decision-making capabilities and exercise them in fact;

Decide and/or manage the DEMPE budget and funding;

Determine and manage development/enhancement IP projects;

Determine how to scale the development/enhancement of the relevant IP;

Determine third-party technology partners involved in the IP;

Deploy the relevant technology in key locations, for related-party and third-party use; and

Centralise the development, enhancement, and maintenance functions in a location that maximises the group use of IP across multiple locations.

Within the above-mentioned parameters, multiple locations may assist the DEMPE decision-making locations in developing the digital technology IP and a case can be supported for remuneration on a cost-plus basis.

These two questions have a direct impact on transfer pricing remuneration, which would need to be determined. Since it is extremely difficult to evaluate the impact of technology IP on a business at the time of development, it is challenging to develop a transfer pricing charge for such models.

It may be important for insurance MNCs to consider the principles of cost contribution arrangements (CCAs) embodied in the OECD Guidelines specifically focusing on development CCAs. Alternatively, if the technology IP has attributes of being licensed to third parties on a pay-per-use basis, then such models may be adopted in the case of related parties as well.

Conclusion

The insurance brand IP example highlights how the characterisation of IP can change over time and can be challenged by tax administrators. The digitalisation technology IP example draws attention to how challenging it is to address transfer pricing in one of the top investment areas for most insurers.

Whether the task is reviewing a transfer pricing position taken with respect to a long-held insurance brand or a first-time assessment of the transfer pricing implications of digital insurance platform investment/other technology innovations, the depth of work one does with respect to business strategy, IP funding, and DEMPE decision-making controls and locations drives any ability to design transfer pricing best suited for the commercial and tax risk management needs.