Certain municipalities are charging property taxes from financial institutions to provide mortgage financings in Brazil.

Following the path of decisions concerning taxes over automobiles the judicial courts, in São Paulo State, understood that municipalities can charge municipal property taxes (IPTU) from the creditor when the debtor fails to pay it. This can increase the cost and availability of financing and therefore reduce the growth of the real estate industry which is a very important source of employment and endogenous growth to the overall economy.

Moreover, the real estate industry is also an important source of municipal taxes on construction services, taxes on the transfer property, and it creates new local homes and increases the overall local wealth, consumption, and employment. Why then are the municipalities killing their golden goose? Is it to further drain taxpayers or just another attempt to pass-off tax collection duties to financial institutions?

This article discusses the fiduciary sale agreements, their importance to the real estate industry in Brazil and the motivations behind the recent judicial decisions.

Fiduciary sale agreements in Brazil

Financing for the acquisition of durable goods is often made through the so-called ‘secured fiduciary sale agreement’. Under this agreement, the grantor receives ownership of record of the good/asset while the debtor maintains the right to use and enjoy it. The grantor cannot use or sell the property until such time when the debtor is under default. The ownership of record therefore is temporarily empty of actual rights of use and disposal of the property, serving in essence as a financing collateral. Once the term of the agreement is complete and the loan is fully repaid, the grantor must return the registry of record to the debtor.

The fiduciary sale agreement has a lower cost and settlement risk as compared to alternative pledging arrangements and was created to boost the credit market in Brazil.

Real estate industry is important for economic growth

Fiduciary sale agreements increase the offer of credit and reduce the credit spreads to the real estate industry which often is the backbone of a country’s economy. As reported by the Brazilian Chamber of Construction Industry (CBIC), the civil construction represents over 7.1% of the Brazilian GDP, and generates over BRL 278 billion (approximately $49 billion) in goods and services transactions, represents around 44% of all investments made in Brazil.

The construction industry is also a great multiplier of production and commerce. CBIC estimates that every BRL 1 invested in housing construction reflects a total investment of BRL 2.46, considering the induced effects on the sector itself on the supply chain – i.e. the investment of this BRL 1 in the construction industry will increase the country’s GDP by BRL 1.12 and the tax collection by BRL 0.62. This market however is deeply dependent on finance.

Tax burden on loans and credits in Brazil keeps financing costs high

However, Brazilian real estate credit markets are still a developing business. Reuters reported in late 2020 that outstanding mortgage loans totalled BRL 720 billion, or around 10% of Brazilian GDP, which is less than half the ratio in Chile and one-fifth of the ratio in the US.

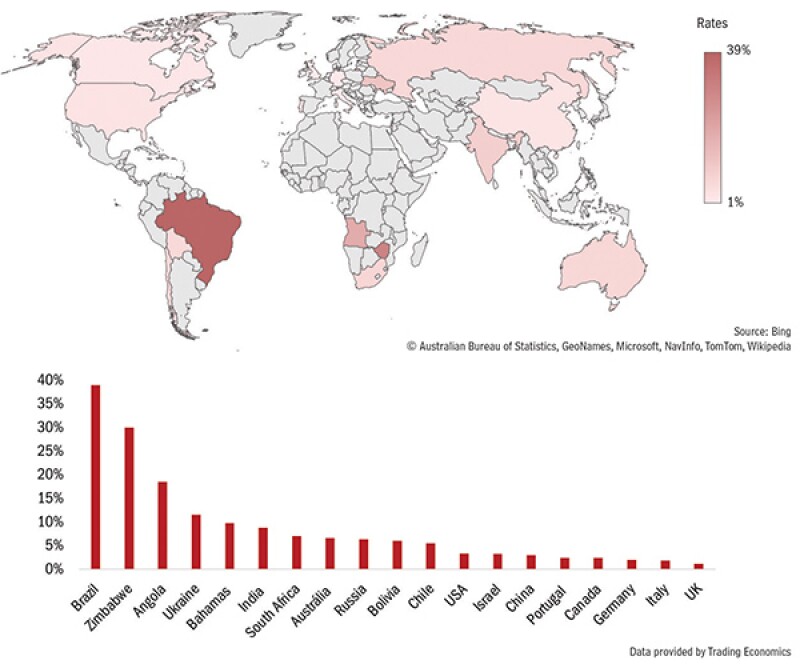

One of the reasons for this shy performance is the fact that Brazil has some of the world’s most costly lending interest rates. According to data available by Trading Economics, the Brazilian Bank lending rates in 2021 surpasses those from other developing countries such as Russia, India and South Africa (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Worldwide bank lending rates (Q4 2020 – Q1 2021)

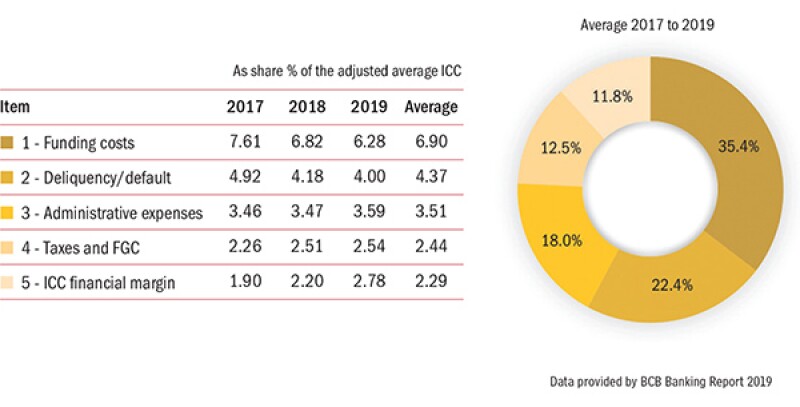

As to the composition of such astonishing rates, studies by the Brazilian Central Bank (BCB) have identified that the main determinant factors composing the so-called ‘average cost of outstanding loans’ (Indicador de Custo do Crédito – ICC), can be grouped into the following five components:

1) ‘Fundraising cost’: Interest paid by financial institutions on their individual funding;

2) ‘Delinquency’: Losses arising from non-payment of debts or interest, including discounts granted;

3) ‘Administrative expenses’: expenses such as personnel and marketing, incurred by financial institutions when performing credit operations;

4) ‘Taxes and FGC’: Taxes paid by borrowers and financial institutions. Customers pay the tax on financial operations (IOF). Financial institutions pay PIS/COFINS and corporate income taxes (IR/CSLL). Also, institutions associated to the credit guarantor fund (FGC), must contribute on a monthly basis a certain percentage of the guaranteed accounts balance; and

5) ‘ICC financial margin’: The portion of the ICC that remunerates the capital shares of the institutions for credit activity and other factors not mapped by the methodology, such as errors and omissions in the estimates.

According to data provided by the BCB Banking Report 2019, the composition of the credit costs pie has been relatively steady. On average, funding costs amounts to 35.4% of the total value, delinquency losses represent 22.4%, followed by administrative expenses at 18%, taxes at 12.5% and, finally, financial profits at 11.8% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: ICC decomposition

Note that taxes are higher than profits. In Brazil, banks pay corporate and turnover taxes of around 50%, soon to increase to 55% (consider the increase of CSLL taxation from 20% to 25% effective as of July 2021, through January 2022). Further burdening taxpayers, provisions for losses in cases of default are not deductible for corporate income tax purposes, only the actual losses are, with a lag of two years no less. The corresponding corporate tax is a hidden additional tax cost not included in the pie chart.

The recent judicial decisions on IPTU levy/taxation, as discussed in this article, threaten to further increase the tax costs, to effects beyond those shown in the pie chart.

Property taxes and the potential impact on real estate finance

To assess the potential impact of the property taxes on real estate finance take for example a family financing 50% of their house purchase in the City of São Paulo, nearby the famous Avenida Paulista. The bank would charge around 7% (A) of interests (interests for real estate financing are lower than for other credits), and the municipality would be charging around 1% (B) of property tax over 100% of the value of the property, which represents 2% (2B) over the total financing amount.

Charging this tax against the bank would imply in an added cost, with a corresponding increase of the financing’s interest rate of around 28.6% (2B/A). This could certainly be a goose killer if it is an unexpected and unaccounted cost for the financial institution, as it is more than twice its actual profits in the transaction (estimated at 11.8%). This could spell a very unpleasant surprise for outstanding and past financings.

A possible solution would be for the financial institution to safeguard itself from such charges and act as a collecting agent of the property tax while financing real estate transactions.

Normally, the debtor would pay the municipality, whereas in this case the debtor will pay the bank and the bank will pay the municipality. So, the overall cost for the debtor and the bank should stay the same, with the only increased cost for the bank to act as collecting agent. Therefore, maybe, the municipalities may not wish to kill the goose but rather to exact even more golden eggs.

It is very common in Brazil to transfer the burden to charge and collect taxes to private agents and banks play an important role of collecting and paying multiple taxes at a nonetheless high administrative and compliance cost and risk.

What are the municipalities’ arguments and their potential flaws?

The argument by the tax authorities to collect property taxes from financial institutions is because the Brazilian Tax Code establishes that the taxpayer for the property tax can be either the user of the property or its proprietor. But what does it mean to be the proprietor of the property? Municipalities adopt a very formal view and consider that the owner of record of the real estate is the proprietor.

However, property taxes are not stamp taxes, they are not applied over registrations, but rather on actual property rights. Financial institutions do not enjoy any of the actual property rights since they do not have the right to sell or use the property until the debt is in default. They only have a fiduciary right over the property.

Charging property tax from fiduciary owners who do not enjoy the rights that justify the taxation of property is, in our view, against the constitutional principle of tax capacity. Interpreting property as a piece of paper is undermining its ancient meaning as the right of use, dispose and sell, which comes from a time when paper and registry did not even exist.

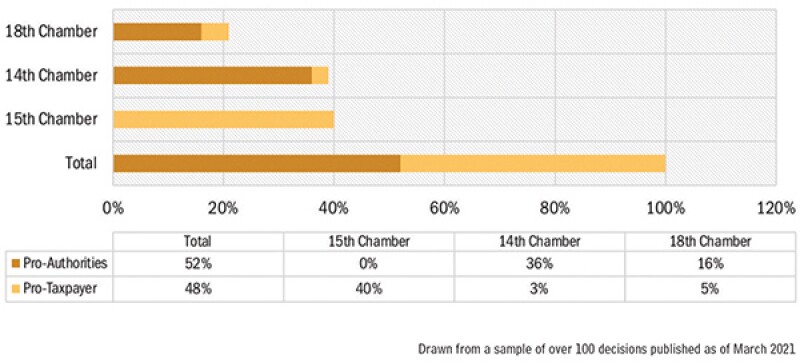

As per our analysis of a sample of over 100 decisions published as of March 2021, decisions by the São Paulo judicial courts in the first quarter of 2021 showed that two out of three judging chambers are more favourable to the tax authorities and, on the overall score, decisions turned out half favouring municipalities and half favouring financial institutions (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Tribunal de Justiça de São Paulo precedents on IPTU liability for financial institutions (Q1 2021)

This discussion is not entirely new as similar cases took place involving vehicle property taxes (IPVA). Much of these discussions were settled through amendments to the local legislation in each state.

To further complicate the banks’ position, the IPTU bill is charged to their name as owners of register of the house/building and, as such, lack of payment results in the immediate and unwarned registration of the bank’s name under the ‘delinquent taxpayer registry’ (dívida ativa). This registration can seriously affect the ability to do business, especially with government entities. By planning ahead some financial institutions have created intervening credit vehicles to enter into fiduciary sale agreements to avoid the registration of their corporation at the delinquent taxpayer registry.

Conclusion

What is most astonishing in this tax tale is the apparent lack of foresight by the tax authorities with regards to the economic consequences that may arise from this levy of IPTU taxes against financial institutions and the thin line between demanding more from the golden goose and outright killing it. Although it is possible that the Brazilian superior courts may deem it acceptable for the IPTU taxes to be levied against the fiduciary creditors, there are consistent arguments as to why they should not.

It is not difficult to notice that should the credit banks be required to provision against not only the risks of default, but also the IPTU tax risks regarding the fiduciary sale agreements, there will be an additional and even greater weight on the already overburdened credit costs of Brazil. This added weight will serve only to hinder the access of Brazilians to financings and credits, which subsequently discourages greatly the investment on sectors, such as the construction industry, which heavily depend on these financings.

Moreover, as mentioned above, for every BRL 1 invested in the construction industry an increase of BRL 0.62 is generated in tax productions back to the government. Through disincentivising industries such as these, by hastily and overgreedily attempting to overcharge creditors for taxes that are not truly theirs, the tax authorities jeopardise the other tax revenues that ensue from a well working economy.

More cases will undoubtedly be brought up against creditors on the matter of IPTU, however it is hoped that the judicial authorities will be able to observe the harmful consequences that ill-founded decisions may cause on the economy.

It is hoped that such arguments can help bring about an enlightenment on the fragile nature of the economy and how small decisions can have major consequences. The municipalities that do not charge the IPTU from banks may take the lead in boosting their real estate market growth.

Click here to read this article in Portuguese

Click here to read all the chapters from ITR's Brazil Special Focus

Lavinia Junqueira |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner Junqueira Ie Advogados T: +55 11 4550 2784 Lavinia Junqueira is a founding partner at Junqueira Ie Advogados. She has more than 25 years of experience as a lawyer, advising financial institutions and companies, structuring and implementing financial transactions, in Brazil and abroad, and dealing with regulatory and tax issues. Lavinia acts as senior counsel to multinational companies, and has extensive experience in dealing with legal, regulatory and tax issues related to the Brazilian financial market. This includes work for the Brazilian Central Bank on foreign exchange regulations, tax and regulatory advice for financial institutions, and assistance to international banks on structuring and setting up operations. Lavinia is a professor of financial markets taxation at leading Brazilian business law schools, having taught at INSPER (2016–2019) and Fundação Getulio Vargas (2006–2012). |

Diego Enrico Peñas |

|

|---|---|

|

Associate Junqueira Ie Advogados T: +55 11 4550 2784 Diego Enrico Peñas is an associate at Junqueira Ie Advogados providing regulatory and tax advice for the structuring and implementation of complex financial and corporate transactions, both locally and internationally. Diego’s expertise is focused on assisting clients in navigating the complexity of Brazilian law prior to, during and after major transactions, particularly in planning for the incidental corporate taxations – both direct and indirect taxes. Diego is also experienced in structuring both foreign investment in Brazil and Brazilian investment abroad, often assisting clients with understanding the effects and benefits of applicable double tax treaties, as well as the potential limitations of Brazilian thin capitalisation and TP rules. Diego holds a bachelor’s degree in law from Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo. |