For some time now, an international outlook has been a success factor for many companies. To defend their position in the increasing competition for new markets, customer groups and employees, companies have to measure up against their competitors not only at a national level but also at a global one. Consequently, a growing number of employees are being deployed around the globe by their employers as key contact persons to ensure efficient coordination between the headquarters and the foreign business operations or to gain international experience as part of a personnel development programme.

The most traditional and most common type of international mobility is known as expatriation (long-term assignments), where employees are typically assigned to a foreign entity for three to five years. However, use is increasingly being made of alternative forms of international mobility that may be categorised as short-term international assignments.

Many countries are imposing stricter regulations for foreign professionals and have now begun examining more closely even those foreign employees on short-term assignments to ensure they receive their share in taxes and social security contributions. In this respect, there is an increasing exchange of data between the immigration and tax authorities. One good example is the UK. The UK tax office wants to know exactly who enters the country to work, even if it is only for a short duration. Most of all, they want to know whether business visitors pay their taxes, either in the UK or in their respective home country. For this reason, the UK's tax authority (Her Majesty's Revenue & Customs (HMRC)) has issued new regulations to the agreement governing short-term assignments in the UK.

According to the Short-Term Business Visitors Agreement (also known as the Appendix 4 Agreement), wage tax must be withheld and payments reported on a monthly basis unless the company has a signed Short-Term Business Traveller agreement with the UK tax authorities. The prerequisites for such an agreement include, for example:

The assigned employee comes from a country that has signed a double tax treaty (DTT) with the UK;

The remuneration is not borne by the UK entity; and

An annual report is submitted to HMRC covering all employees who have been deployed to the UK for more than 60 days.

This means that the home companies will have to implement systems to monitor their employees' travel to the UK. Otherwise they are liable to tax withholding payments or other financial penalties.

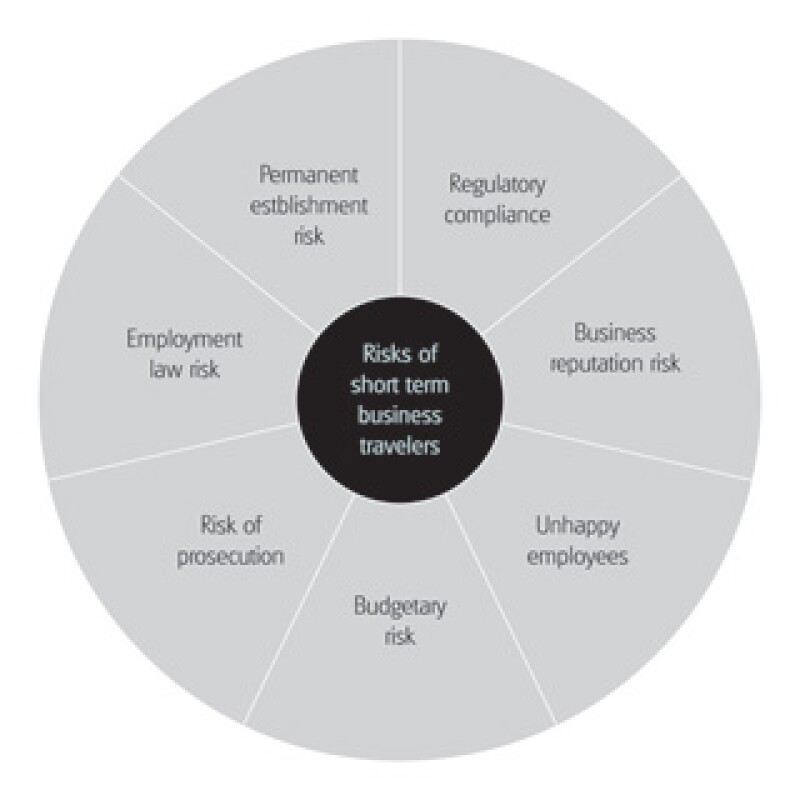

As other countries also have strict requirements, companies are facing a major challenge in this respect. Obligations under residency and work permit legislation are being reviewed less thoroughly in the case of short-term assignees than in the case of long-term assignments. There are many reasons for this: short-term foreign assignments are often decided upon at short notice at the level of individual specialist departments, bypassing HR. This gives rise to considerable risks for the companies involved and their employees. However, in the meantime there is increasing awareness of the risks arising from short-term foreign assignments.

Various types of international mobile employees

International work takes place in a wide range of activities. Due to the legal aspects mentioned above they need to be closely monitored, particularly since these kinds of short-term international activities are constantly on the increase. The most familiar type are project assignments of several months and traditional business trips abroad. When it comes to the latter, employees travel to another country on an ad hoc basis without a formal assignment. So-called international commuters travel across borders on a regular basis because the place where they live and the place where they work are in two different countries. In addition, foreign assignments as part of training and development programmes have now become quite common at international companies. Last but not least, multiple functions within a group also increasingly lead to regular cross-border working activities.

Multiple functions

In addition to their primary activities for their employer from a legal perspective, executives often hold further operating functions for one or more group companies in other countries. At many companies, multiple functions are increasingly being planned for strategic purposes and implemented on a permanent basis. Due to the additional operating function for one or more group entities also outside of the home country, it is necessary to review whether such group entities qualify as an employer from an economic perspective. This may trigger a tax liability on the part of the employee in conjunction with duties to withhold tax and contributions on the part of the employer. To ensure compliance, it is necessary to implement cross-disciplinary processes and guidelines that include clearly defined responsibilities and lines of communication. Defining such responsibilities and procedures and the suitable degree of communication and intense collaboration between the specialist functions involved (specialist department, HR, tax, legal, controlling, finance) is decisive.

One risk group that is increasingly attracting attention are business travellers. Data collection is a fundamental challenge here. The information relating to the travel activities of employees working internationally is often spread around the company. Some employees record their travel activities on a voluntary basis, others are instructed to do so by their supervisors or HR departments. Some companies are using a centralised system to record and monitor business travellers.

183 day regulation: Correct application

Countries justify their right to taxation by the fact that the work is performed in their territory. To avoid double taxation in the home country as well as the host country, there is usually a regulation contained in the DTT based on Article 15 of the OECD model convention.

Generally speaking, the right to tax income from dependent employment is allocated to the country of residence of the employee on assignment, unless the place of work or source state principle applies. In this respect, it is necessary to first clarify in which country the employee is deemed resident, whether residency was relinquished during the short-term assignment or whether the employee is deemed resident in both the home and the host country.

Once home and host countries have been defined, a review is performed in a second step to determine which country is attributed the right to taxation for which income. Pursuant to Article 15 of the respective DTT, the right of taxation may only revert to the country of residence if all of the following three criteria are met:

The employee does not spend more than 183 days in the host country within a given 12-month period as defined in more detail in the applicable DTT; and

Remuneration is paid by, or on the behalf of, an employer that is not a resident of the host country; and

The remuneration is not borne by a permanent establishment (PE) of the employer in the host country.

The term '183 day regulation' has established itself as the measure for such situations. Consequently, many people only look at the 183 day threshold and do not sufficiently review the other two aspects. This can have costly consequences, however: if the employer or a permanent establishment is located in the host country (that is, criteria 2 and/or 3 are not met), the employee on assignment will be liable for tax on income from employment from the very first day in the host country.

Even the method of counting the 183 days is often a challenge. DTTs may refer to three different twelve-month periods: the tax year, the calendar year or any twelve-month period beginning or ending in the tax year in question. The tendency is to apply a discretionary twelve-month period. This makes forward planning of foreign assignments all the more important. When prescribed periods are exceeded, retroactive taxation becomes necessary, which is often not easy to comply with and may lead to double taxation.

Additional attention is necessary in case of board members, managing directors and individuals having power of procuration. In these cases some DTTs allocate the right of taxation to the country of the management of the company, irrespective of working days in this country.

Who is the employer?

The OECD model convention does not contain a definition of its own. The term employer is to be interpreted primarily according to the sense and purpose and in the context of the convention and only secondarily according to national tax law. But even this is difficult. Even if the legal employer remains in the home country, there may be an economic employer in the host country.

This blurring can lead to different interpretations by the countries involved. For this reason, the OECD has reworked its model commentary. According to the OECD commentary, it is only possible to reinterpret the legal employment relationship under certain circumstances. For example, the host company generally becomes the employer when the employee performs essential tasks for that company, for which that company assumes responsibility and the risks arising from which it is willing to assume (integration test). Further decisive factors are which company has the right to issue instructions to the employee and who, from an economic perspective, bears (or should have borne) the cost of remuneration.

Finally, from a German perspective, it is of special importance who actually bears the expense of the wages according to the general regulations on the allocation of profit between affiliated companies or should have done so applying the pertinent arm's-length principles. In the case of an assignment to Germany of more than three months, the German tax authorities generally work on the rebuttable presumption that the assigned employee is integrated into the host company in the host country and that the latter thus qualifies as economic employer. Consequently, the employee becomes liable to tax from the first day of employment in Germany onwards, even if the employee is there for less than 183 days. Companies whose employees are only briefly in Germany should, in the case of more than three months, be able to clearly document why the employee is not integrated into the German company.

Permanent establishment risk

Foreign assignments of employees give rise to the risk for employers establishing a PE in the host country. Especially in emerging economies, the tax authorities are increasingly attempting to construct a PE of the assigning company from the activities in the host country. Even if there is already a foreign subsidiary in place, additional PEs for tax purposes may arise in the same country.

The first issue to be clarified is always whether the work performed by employees abroad constitutes a PE as defined by the relevant DTT. The definition contained in the respective treaty is definitive for the term permanent establishment (cf. Article 5 OECD-MC).

For example, protracted on-site assembly work abroad may mean that companies form what is known as a permanent establishment for assembly purposes. This affects, for example, German companies that build turn-key facilities abroad in the capacity of general contractor. In the case of assembly work, office containers may constitute a fixed place of business as defined in Article 5 (1) OECD-MC from which the business operations of the company are performed. If there is no fixed place of business, the criteria for a PE for assembly purposes as defined in Article 5 (2) OECM-MC will have to be reviewed. According to that article, a construction or assembly site only becomes a PE after a period of more than twelve months; this is the case for example in France, the UK, South Korea, Italy and Poland. In China, India or Mexico, in contrast, exceeding a six-month period is sufficient for a PE for assembly purposes to be formed. Some countries provide for a nine-month period.

In China, a PE for the provision of services can be formed even by the rendering of services over a period of more than six months. The remuneration for the days worked in China attributable to the PE are all subject to taxation in China. Even in cases where the salary expenses are cross-charged to the Chinese entity with a markup, there is an increased risk of the existence of a PE in China being assumed due to the deployment of employees. Similarly, mobile sales staff with de facto power to sign contracts may postulate a PE for sales representatives of the company assigning them to the host country.

The assumption of the existence of a foreign PE has considerable tax implications. The assigning company becomes subject to limited tax liability under the respective national tax law with regard to the income attributable to the PE from an economic perspective. Any profit generated by the PE in this country must be taxed in the host country. The 183 day rule would not apply to the assigned employee, which means that the employee may be subject to personal income tax liability from the very first day of work in the country where the PE is located.

Assigning responsibility

All these risks underscore the necessity of proceeding in an organised manner when it comes to short-term international activities and responsibilities. In-house regulations and processes help to maintain an overview and to comply with various legal systems. In many cases, the various corporate functions – whether HR and tax departments or line managers – that send employees on foreign assignments are themselves aware of the associated risks. However, responsibilities are often insufficiently defined.

The international HR department working together with the tax department should take the lead here and, as a first step, communicate to all stakeholders involved the necessity of a structured solution for short-term foreign assignments and international activities and responsibilities. Inter-departmental cooperation is essential. Both the specialist and operating departments as well as the internationally working employee are responsible for achieving the path to compliance.

Policy

Internal guidelines for short-term foreign assignments and international activities that trigger tax in various countries are recommendable for all agreements and decisions relating to responsibilities, recording travel data, communication and processes. These guidelines must clarify the following issues:

Which employees are covered? (This often defines threshold values. For example, all employees anticipated to be traveling for at least 30 or 90 days to a specific country are covered).

How is this data recorded? (For example, by the employees themselves using Excel lists or using a central tracking system or with the assistance of a central travel booking office)?

When is which information conveyed to which responsible office (for example, international HR department)?

In this respect, it is necessary to make the specialist and operating departments and the employees themselves responsible for compliance with the policy.

Interdepartmental cooperation is central to successful management

The challenges and risks of cross-border foreign activities are manifold and complex. Companies still do not pay sufficient attention to short-term foreign assignments and activities. This gives rise to compliance risks of a corresponding magnitude. Monetary fines, withholding requirements and damage to reputation can be incurred. The management of international activities requires a structured interdepartmental cooperation between HR, tax, operating departments and employees. Only when responsibilities have been clearly defined and processes and transparent policies have been put in place, will it be possible to manage short-term assignments and international activities properly.

This article is an abridged version of a German article that was published in the Tax & Law Magazine 2014Q1. The article includes findings of the EY Global Mobility Effectiveness Survey. The most recent 2013 survey can be found at www.ey.com/GL/en/Services/Tax/Human-Capital/Global-Mobility-Effectiveness-Survey-2013.

Biography |

||

|

Ulrike Hasbargen Partner German public auditor / tax adviser Head of human capital in Germany Switzerland and Austria (GSA) EY Arnulfstrasse 59 80636 Munich Tel: +49 89 14331 17324 Mobile: + 49 160 939 17324 Email: ulrike.hasbargen@de.ey.com Ulrike Hasbargen has been a partner at EY since 2000 and today heads our Human Capital service line in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Her advisory work includes all topics relating to the challenges connected with international mobile employees (global mobility, global equity, strategy, process optimisation, policies, compliance). |

|