Many multinational financial institutions (FIs) operating in China have had their intragroup service fees and royalties scrutinised by the Chinese tax authorities in the past few years.

This has been part of a broader State Authority of Taxation (SAT) focus on large outbound payments since 2012. Most of the tax authorities' reviews of FIs' outbound payments had been focused on the concept of benefits, and in particular, what benefits were provided by the services or intangibles to the Chinese entity in question.

Many of the inquiries by the local tax bureaus resulted in stalemates, because proving benefits provided turned out to be difficult, and the tax bureaus' concern that some of the services rendered may have been stewardship services, or duplicative in nature, required substantial amounts of evidence as part of the review process.

Another difficult challenge was the lack of an official definition of some of the "benefit tests" in the current Circular 2 – Special Adjustments Implementation Measures issued by the SAT. Circular 2 is China's primary transfer pricing administrative guidance.

Lastly, the view of financial regulators such as the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) on what is an allowable service or royalty is also unclear. All these factors led to an uncertain environment for multinational FIs, which are also under pressure in their home locations to ensure that appropriate costs are charged out to affiliates that have benefited from the services or the intangibles for tax and regulatory purposes.

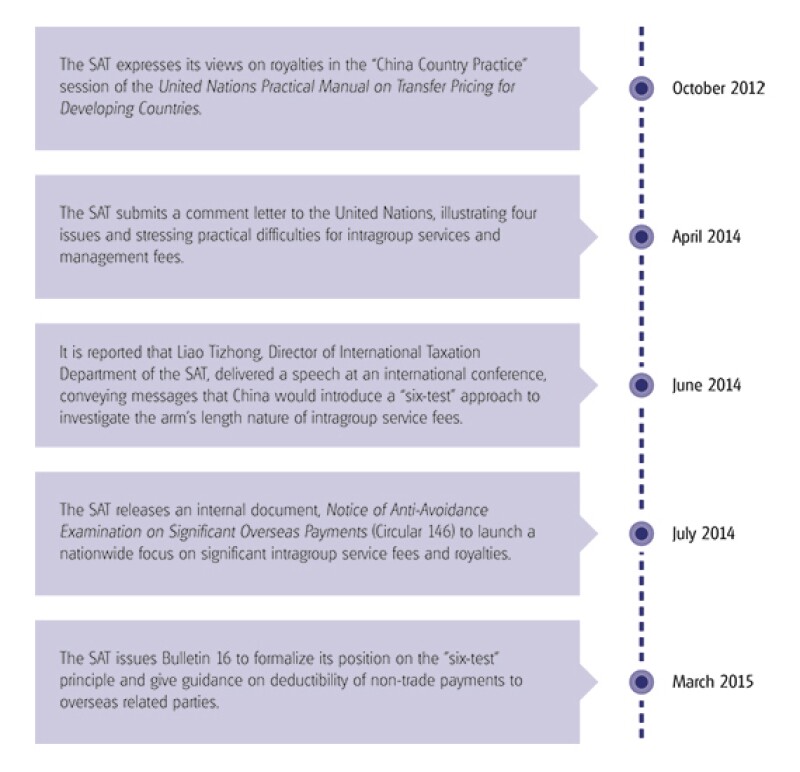

The SAT stated its views on a number of transfer pricing subjects in the United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries, issued in 2012, and in a subsequent comment letter regarding services issued in 2014. Now, after a number of preliminary measures, the SAT has formalised its position with the issuance of Bulletin 16 in 2015 (see Diagram 1).

Diagram 1 |

|

The benefit tests introduced by Bulletin 16 are consistent with the OECD's historical approach to analyse the reasonableness of service fees. The language used in Bulletin 16 is consistent with the discussion draft issued by the OECD under its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative regarding low-value-adding intragroup services, which provides that a benefit test will be performed to evaluate whether "the activity provides to a respective group member with economic or commercial value to enhance or maintain its commercial position…."

While the concepts behind some of the SAT's current "six tests" (the benefits test, necessity test, duplication test, value creation test, remuneration test, and authenticity test) sometimes overlap, the clearer language of Bulletin 16 now clarifies the SAT's view of what factors are important in evaluating the reasonableness of service fees. The tests themselves are broadly consistent with the OECD's own benefit tests in terms of stewardship and duplicative and other activities that do not provide benefit to the service recipients, although the terms used may be different. It also reflects the SAT's effort to implement parts of the BEPS Action Plan domestically.

In the context of services fees and royalties paid by FIs to related parties outside China, the various benefit tests now stack up as follows:

Economic value benefit test

Article 4 of Bulletin 16 treats payments for "incidental" benefits as nondeductible. This position is in line with the current OECD view on services as expressed in the BEPS discussion draft.

Article 6 also denies the deductibility of royalty payments to overseas related parties for "incidental benefits" derived from the financing and listing of the holding company – that is, royalty payments to overseas headquarters that claim that the listing of the group enhances the reputation of the PRC subsidiary.

The SAT has stated specifically in Article 2 of Bulletin 16 that there will be no deduction for royalties paid to recipients that are IP box-type companies with no commercial substance. This of course does not mean royalties are never allowed. However, it does mean that to get the royalty deduction, the PRC entity must show that the fees or royalty recipient has provided demonstrable and perhaps quantifiable benefits to the PRC entity through ongoing "DEMPE" functions (developing, enhancing, maintaining, protecting, and exploiting intangibles) and related investments, rather than merely through group association.

In other words, an extensive global network of bank branches with a well-recognised brand cannot be the primary basis of a royalty charge. The taxpayer now must demonstrate that the legal IP owner charging the royalty has to actively drive the ongoing development, enhancement, or maintenance of the brand, and that the PRC entity can reasonably exploit said brand in the China market because of these ongoing efforts by the IP owner. For example, has the development cycle considered perception of Chinese banking or insurance customers? What China-specific marketing and branding activities were implemented, and what are the expected financial and non-financial benefits specific to China?

Necessity test

The SAT advocates that consideration should also be given to whether the PRC subsidiary needs the services subsidiary, and what are the direct and indirect benefits received. For example, if a multinational insurer allocates product development costs to its global affiliates, but the PRC subsidiary does not have the required regulatory approval or capital to sell some of the products being developed, it may be difficult to demonstrate direct benefits. At the same time, would it be possible to demonstrate indirect benefits if the PRC entity is in the process of seeking approval for selling such products in China?

Value creation test

As noted above, services can create value when they are able to bring in identifiable enhancements of economic and business value – improving the service recipient's operating performance. Of particular concern to the SAT are service payments to parent companies just for providing authorisation services to the local country management. In those situations, the SAT believes those services are simply management services that serve as a procedure instead of creating identifiable economic or commercial values, and therefore they should not be charged. While this may be viewed as consistent with the OECD's approach to stewardship or custodial costs, for FIs around the world, substantial and ever-increasing efforts and costs are spent on improving controls and ring-fencing risks. The question of how much of these costs is spent for shareholder protection and how much is for risk mitigation for the specific local entities and their local customers can be a complex one.

Duplication test

This test is consistent with existing OECD guidelines, and it also appears in the discussion draft issued by the OECD on low-value-adding services: ". . . no intra-group service should be found for activities undertaken by one group member that merely duplicate a service that another group member is performing for itself, or that is being performed for such other group member by a third party". Because they are large, complex, and sometimes matrix organisations, multinational FIs often have departments and cost items that have similar names and/or descriptions. It is not unusual for such FIs to have information technology or human resources departments at global headquarters, regional headquarters, centres of excellence, and local entities. The challenge is for the organisation to explain (and provide evidence) to the local tax authorities the differences among these similarly named departments, and how different people in different places work together to deliver a combined result.

Remuneration test

The SAT points out that when analysing intragroup services, consideration should be given to whether the provision of various services has already been remunerated through other related-party transactions. For example, if a profit split method is already utilised for investment banking activities, then foreign costs related to those activities should not be allocated as part of overall intragroup services. As another example, when a PRC entity is only a limited-scope investment research entity, then its routine return for its limited role in the global value chain should not be reduced by intragroup service costs unless it then forms part of its arm's-length cost base.

Authenticity test

Under Bulletin 16, the in-charge tax authority has the right to request relevant documents to substantiate the authenticity and arm's length nature of a service transaction. Enterprises can be challenged if they do not have the relevant information and documents prepared and filed in advance. Depending on your view point, this may be an extra hurdle for many taxpayers in China, or from a practical perspective, already an existing hurdle.

Cost Contribution Arrangements

On April 29, 2015, the OECD released a non-consensus discussion draft on cost contribution arrangements (CCAs) that contains proposed revisions to Chapter VIII of the OECD's transfer pricing guidelines in relation to BEPS Action Plan under Action 8 (transfer pricing valuation with respect to transfers of intangibles).

Consistent with the current guidance, the CCA discussion draft applies to both service CCAs, in which participants share the cost of services, and development CCAs, in which participants share the costs and risk of developing property. The CCA discussion draft takes the position that the outcome of operating within the context of a CCA should be the same as if the CCA had not existed. Therefore, both initial contributions to the CCA and ongoing contributions must be measured by value rather than cost. The CCA discussion draft provides one exception to this rule for low-value services, for which valuation of contributions at cost is permitted. The requirement that contributions be based on value rather than costs is more limiting than the current guidance, but aligns with the BEPS Action Plan and the increased emphasis on value splits. Nonetheless, the requirement to use value rather than cost is the change likely to have the greatest impact on existing CCAs.

In China, the current Circular allows for the use of CCAs; however, it does not provide detailed guidance on the implementation. While the OECD CCA discussion draft provides significant updates of the existing global guidance, there remain a number of uncertainties as to how it can be successfully implemented in China. Setting aside some of these issues, such as local valuation principles and potential location-specific advantages in China, the prospect of using CCAs in China brings out two interesting points with respect to intragroup services payments.

It seems possible that the SAT may also apply benefit tests similar to those introduced in Bulletin 16 when reviewing a service CCA involving Chinese participants. For example, the SAT may focus particularly on the review of the determination/classification of the cost pool (for example, whether stewardship and non-beneficial expenses have been inappropriately included), how the participants are determined (whether the participants have made a contribution and benefit from the CCA, especially for those participants located in low-tax jurisdictions), etcetera.

Second, because a CCA is premised on all participants sharing not only contributions but also risks of the CCA activities, to qualify as a participant in a CCA an entity must have the capability and authority to control the risks associated with the risk-bearing opportunity under the CCA. This part is consistent with both the overall BEPS Actions on intangibles and value contribution as well as the SAT's stated positions on the subject.

The SAT's views have been repeated in the UN Manual (released on 2 October 2012) and Administration Plan for International Taxation Compliance in 2014-2015, by Jiangsu Provincial Office of SAT in April 2014. The SAT put emphasis on functions performed, assets used, and risks incurred at local Chinese entities, and the transfer pricing outcome should be in line with value creation. However, does this also mean that the SAT will accept situations where, for example, significant IT costs are invested globally by a bank or an insurance group and operating losses are driven by current-year CCA-related activities since the relevant China entity will in effect be a local entrepreneurial entity (for CCA-related business lines) and not be subject to loss limitation such as those outlined in Circular 363 assuming the benefit tests are properly addressed?

As a practical matter

Bulletin 16 and its interpretation make it clear that there is no need to obtain preapprovals from the tax authorities for overseas remittances of service charges or royalties. However, upon request by the tax authorities, the domestic payer is required to submit the intercompany agreements and other supporting evidence to substantiate the authenticity and arm's-length nature of the transaction. As noted above, there is a clear emphasis on being able to prove the authenticity of the service being provided, something that can be particularly difficult for some types of services being provided in a global FI environment. The tax authorities will have the right to perform a tax adjustment on any noncomplying transactions within a period of 10 years, and evidence of services should be maintained contemporaneously.

So while Bulletin 16 provides more common languages between global FIs and the tax authorities than prior rules, it does not resolve many of the practical challenges when the discussion turns to the details. Benefits, measurement issues, and types and amount of required back-up evidence may likely continue to be sources of transfer pricing controversies in China in the near future. The insight into the SAT's view point from Bulletin 16 does provide some valuable clues for multinational FIs with intragroup services and royalties to design and implement transfer pricing structures and evidence-collection mechanisms that will improve their chance of successfully deducting services costs in China.

|

|

Patrick CheungTax partner – FS tax transfer pricing Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Tel: +852 28521095 Fax: +852 25206205 Patrick is a transfer pricing partner and the financial services transfer pricing leader for Deloitte China. Before joining Deloitte, Patrick was a financial services transfer pricing partner of another Big 4 accounting firm in Hong Kong. Patrick began his Big 4 international tax and transfer pricing consulting career in Canada. Before that, he worked for the Canada Revenue Agency. Patrick is recognised by LMG's Expert Guides as a Leading Transfer Pricing Adviser in Hong Kong ExperiencePatrick has deep experience in all kinds of transfer pricing projects, from general compliance to supply chain planning and implementation to dispute resolutions and advance pricing arrangements. His financial institution clients include major international commercial and investment banks, insurance and reinsurance companies as well as asset management firms. Project experienceSome of Patrick's project experiences include:

Patrick is also a frequent speaker at PRC State Administration of Taxation national training events on the subject of financial services transfer pricing and at other industry forums. Patrick is a graduate of the University of Toronto and a CPA, CMA. |

|

|

Johnny FounPartner | Global Business Tax Services Deloitte Tel: +86 21 61411032 Johnny is a tax partner of Deloitte Shanghai office with 18 years professional experience in China Tax. Johnny has been advising multinational corporations (including banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions) on China tax and investment, restructuring of overall China investments to achieve tax efficiency, providing business consultations, value-added tax and other turnover tax consulting. |