As outlined in last year's China Looking Ahead chapter on research and development (R&D) tax, Better smart than lucky: China R&D incentives 2.0, innovation is viewed by Chinese policymakers as crucial to maintaining the momentum of China's economic development. Adding emphasis to this, in a series of speeches in 2018, President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang made clear that domestic development of new core technologies is a crucial national objective for the years ahead. This is particularly so in the face of the new international trends affecting globalisation.

President Xi has stated: "Given the increased size of China's overall economy, complete reliance on foreign countries for science and technology innovation is not a sustainable policy. While we will maintain unswerving commitment to the opening-up policy, we should also look to drive independent and indigenous innovation."

Premier Li has observed that "innovation is the main engine of economic development and shall be the centrepiece of the country's overall development strategy". Mapping to this statement, a national science and technology leader team, led by Premier Li, was recently established to drive innovation in key and core technologies.

It is therefore in line with these statements that China has made a number of notable improvements to its innovation tax incentives in 2018.

Economic context for tax policies encouraging innovation

The economic context of China's updated innovation tax policies has both external economy and internal economy dimensions.

On the external economy side, as a result of the US tax reform in December 2017, further thought has had to be given to China's tax attractiveness for innovative activity. The income tax rate of US enterprises has been lowered, a 100% expensing of capital investment has been introduced (for a five-year period to 2022), and a type of patent box regime (FDII) has been promulgated; see the chapter, When America squeezes – implications of US tax reform for China, for further details. All these collectively make the US a more attractive location than previously for new investment in both high tech tangible investment (e.g. robotic factories) and new technologies. At the same time, the US base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) rule discourages the purchase of outsourced R&D services from overseas, potentially affecting the development of the R&D service export sector in other countries.

These changes, coupled with the US tariffs now being imposed on a broad range of Chinese exports (see the chapter, In the eye of the storm – how does China act and react in times of trade tension?), raise the question as to whether foreign investment in China, fostering technological development and economic upgrade, will diminish. It also raises the question of whether China's own domestic development of innovative new products and services for export will be stymied. Against this backdrop, China's innovation tax incentives are becoming ever more important.

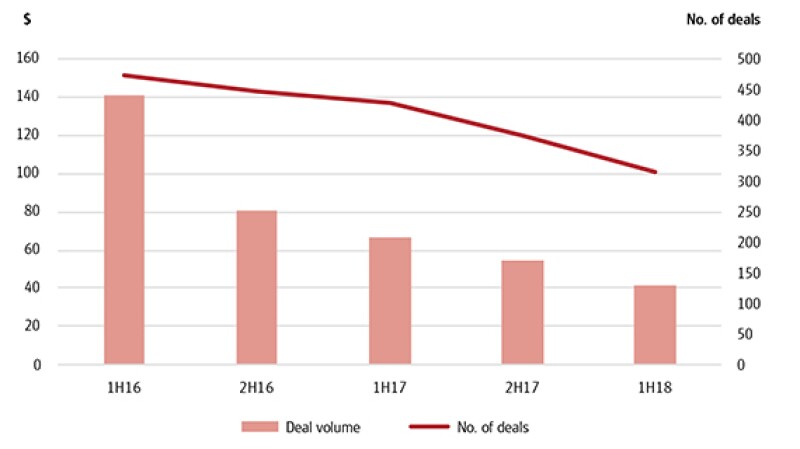

A further consideration is that, while Chinese investment into European and US technology firms had rapidly increased in recent years, from 2018 Chinese enterprises have faced increased hurdles in obtaining access to key developed country technologies. This holds both in relation to technologies obtained by way of import into China (e.g. inbound licensing) or by way of Chinese enterprises purchasing developed country technology companies. The fall in Chinese outbound M&A, detailed in the Thomson Reuters statistics set out in Diagram 1, is reflective of the new challenges created for making these overseas acquisitions. Greater scrutiny from the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), and moves in the same direction in Germany and the UK, have played a role here; though it is noted that the investment decline also reflects falls in Chinese investment in speculative real estate and entertainment assets as a result of tighter restrictions set by the Chinese government. This developed country regulatory trend compels Chinese enterprises to seek alternative routes to industrial upgrading.

Diagram 1: China announced outbound M&A 1H16 to 1H18 – in USD and no. of deals

Moving to the internal economy dimension, China's economy grew at 6.5% in the third quarter, the weakest quarterly expansion since 2009. At the same time, fixed-asset investment growth in the first eight months of 2018 dropped to its lowest level since 1995, at just 5.3%. This was a fifth consecutive record low. What is more, the IMF has estimated that in the worst possible outcome for the development of trade issues with the US, Chinese growth could decelerate to 5% in 2019. Looking ahead, President Xi and other top officials have repeatedly emphasised the importance of deleveraging the economy to reduce risks in China's financial system. This means that China cannot rely on expansive monetary policy, easy credit for large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and local government infrastructure projects, and the real estate boom for growth, as in the past, and new drivers need to be explored.

It is in this context that China is taking action to leverage innovation as a response to its external and internal economic challenges. Policymakers are working from what is already a fairly solid base in terms of outlays on R&D the effectiveness with which they are being used, and the financial support for innovative enterprises.

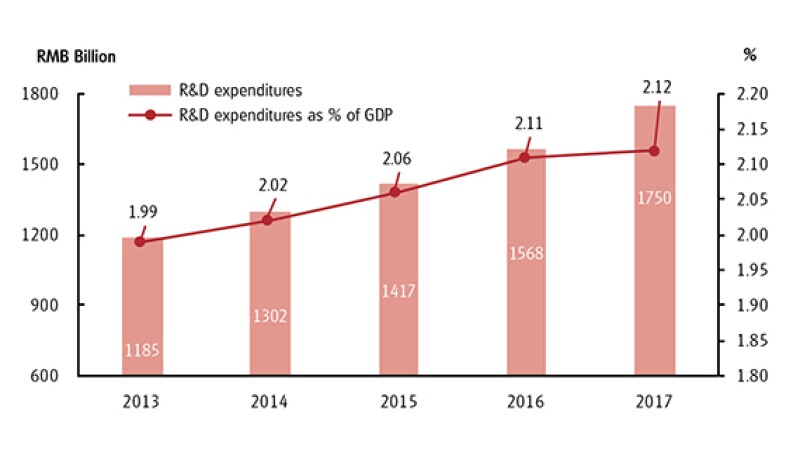

According to a 2017 statistical bulletin from the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, in 2017, R&D investment in China reached RMB 1.75 trillion ($251 billion), and 2.12% of China GDP (see Diagram 2).

Diagram 2: China’s R&D expenditure 2013 to 2017 – in RMB billion and as % of GDP

In the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) 2018 Global Innovation Index (GII) report it was noted that, since 2016, China has featured in the 'Top 25' group, being the only middle-income economy to do so. China has consistently moved upwards in the rankings, to 17th in 2018, meaning that it ranks ahead of developed countries such as Canada (18), Norway (19), Australia (20), and well ahead of other BRICS countries (e.g. Russia ranked 46). The WIPO also evaluated China as performing well at transforming inputs (e.g. investment in education, high R&D expenditure, etc.) into high-quality innovation outputs, performing better than Singapore, Japan, Canada, Norway, and others in this regard.

Also of key importance is the rapid growth of the Chinese venture capital (VC) industry. As the Chinese digital economy giants, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent (collectively referred to as the 'BAT') stand behind approximately 50% of all Chinese VC investment, there is a distinct channelling of funds towards digital economy innovation. According to the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) report, 'Digital China: Powering the economy to global competitiveness', China is the leading nation for VC investment in the fintech sector and in the top two for each of virtual reality (VR), autonomous driving, wearables, and education technology. This puts the country in good stead for the future, and complements on the consumer side the efforts on the industrial side to upgrade manufacturing through automation and robotics, under the 'Made in China 2015' programme.

Many commentators now observe that the trade issues with the US may further accelerate the trend already well under way for low-end, low-margin processing activity for clothes, toys, and so on, to be relocated to Southeast Asia and India, and Chinese manufacturing to shift towards middle and high-tech production, including vehicles, electrical and construction equipment, as supported by automation and robots.

Behind these statistics and trends stand the Chinese innovation tax policies, including R&D super deduction, high and new technology enterprise (HNTE) and advance technology services enterprise (ATSE) incentives, expensing equipment of less than RMB 5 million, and so on. We set out below our observations on recent progress made with these measures, and potential future directions.

R&D expense super deduction expanded

As in many countries around the world, China uses an R&D bonus (or 'super') deduction regime to support enterprise innovation. The origins of China's R&D bonus deduction policy can be traced back as far as 1996, but the prevailing R&D bonus deduction framework was introduced in 2015, Caishui 2015 No. 119, (Circular 119).

Before 2017, China provided enterprises with a 150% corporate income tax (CIT) super deduction (i.e. a 50% bonus deduction) for qualifying R&D expenses. This meant an effective cash saving of 12.5% of the value of the eligible expenses incurred (assuming the 25% CIT rate applies). As outlined in last year's chapter, from 2017 the bonus deduction was raised to 75% for qualifying science and technology small and medium enterprises, and this was then expanded nationwide to all enterprises from 2018 according to the latest tax authority guidance issued in September 2018. This brings the cash saving to 18.75% of the value of qualifying expenses incurred. As we can see in Table 1 though, there is still room for further improvement to match the best in the ASPAC region.

Table 1: Comparison of effective bonus deduction rate

China |

Hong Kong |

Singapore |

Australia |

New Zealand |

|

Effective bonus deduction rate |

75% |

100% or 200% |

150% |

128% or 145% |

45% |

While this incentive can be very attractive for businesses, in practice there are quite a few uncertainties and limitations on the relief, due to unclear qualifying conditions. In order to remedy for these, the State Administration of Taxation (SAT) released guidance between late 2017 and mid-2018.

In practical application, local tax authorities have limited the expenses they regard as eligible for the super deduction, in circumstances where the SAT guidance is unclear. For example, with respect to staff costs, the super deduction may be limited in practice to the cost of core R&D staff while other items, such as business trip expenses related to R&D projects, may be denied the super deduction. In SAT Announcement 2017 No. 40 (Announcement 40) and Circular 2018 No. 64 (Circular 64), a broader scope of super deduction inclusion is clarified:

Costs of technical staff and R&D supporting staff, in addition to the core R&D staff;

Salary payments actually made to outsourced R&D staff;

Costs associated with share-based incentive schemes, to the extent generally deductible for CIT purposes;

Other expenses, including staff welfare, complementary pension and complementary medical contribution;

Costs associated with failed and aborted R&D activities; and

Expenses incurred for contract R&D activities outsourced to overseas entities. There is a limitation that only 80% of sub-contracted R&D expenses can be entitled to the R&D bonus deduction, applying for outsourcing to both domestic, and foreign, service providers. This is coupled, in the case of outsourcing to overseas entities, with a further cap providing that foreign outsourcing expenses must not exceed two thirds of the qualifying R&D expenses incurred locally in China.

Building on these enhancements, the Chinese government is now working towards further upgrading China's innovation incentives. The following areas for improvement may be highlighted:

Allow all industries to access the super deduction: The super deduction rules exclude enterprises in certain industries from accessing the super deduction. This is governed by a 'negative list' of industries, set out in Caishui [2015] No. 119 (Circular 119), and covers service sectors including tobacco retail, real estate brokerage, wholesaling and retail, accommodation and catering, leasing and business services, entertainment, and any other sectors stipulated by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) or SAT. It is widely considered unduly restrictive, given that there may be highly innovative companies in these sectors which the Chinese government should be fostering – for example, innovative technology to pack, seal and fill products for a longer shelf life, or innovative construction techniques. Indeed, given that China is looking to shift towards a service-consumption driven economy, this negative list should be abolished – this should help to ensure that China invests sufficiently in the knowledge based capital core to an advanced and successful service sector.

Start-ups need R&D tax incentives to deliver cash refunds: Innovative start-ups generally run substantial losses while they build up their business. As such, they are not in a position to monetise R&D super deductions, which can only deliver benefits where there are taxable profits. Some countries (e.g. Australia, New Zealand, etc.) adopt a cash refund mechanism for such cases. For example, in Australia, the 43.5% tax offset, provided under their R&D tax incentive, is refundable in cash for loss-making entities with turnover less than A$20 million ($14.4 million). Subject to an evaluation of the fiscal impact, the China government should consider this approach. It might be noted that China recently took the measure of refunding excess VAT input credits to businesses in high-tech industries, showing a clear understanding by Chinese policymakers of these cash flow considerations.

Progressive rates steer support to innovative start-ups: Under Hong Kong's new R&D incentive regime, a progressive bonus deduction rate structure provides a 300% deduction for the first HK$2 million ($255,000) R&D expenses incurred, and 200% for any remaining R&D expenses incurred. This maximises support to small-to-medium sized enterprises, and might be considered a better result than having the vast majority of government R&D subsidies flow to a smaller group of large enterprises. Such a progressive rate scheme might be considered by China in the next phase of innovation tax incentive upgrades.

Fine-tuning the HNTE incentive

Another important tax incentive for innovation in China is the HNTE status and the associated 15% reduced CIT rate. In order to obtain the HNTE status, the following criteria should be satisfied:

IP ownership: The company must own the core technological IP which plays the key role in supporting its main products (services);

Industrial field: The main products (services) of the company should fall within one of the eight specified industrial fields;

R&D expenses: The ratio of qualifying R&D expenses to the total sales of the applicant in the preceding three fiscal years should meet the relevant minimum ratio (i.e. 3%, 4%, or 5% for different sales volume levels);

HNTE revenue: The proportion of the revenue derived from high and new technology products (services) to the total revenue of the enterprise is more than 60%;

Personnel: The ratio of science and technology personnel engaged in R&D and related technology innovation activities should be no less than 10% of total employees of the company for the year; and

Innovation scorecard: A calculation of points is conducted using four assessment criteria for the HNTE candidate's operations. A company needs 71 points or more to qualify for the HNTE incentive.

Compared with the changes to the R&D bonus deduction policy, the changes to the HNTE incentive over the past year are relatively moderate with no ground-breaking reform:

Clarification of R&D expenses calculation widens HNTE access: To qualify for the HNTE incentive, an enterprise's annual R&D expense must reach a certain percentage of the company's total revenue (e.g. 5% if the latest annual sales are less than RMB 50 million). This is a problematic rule for many enterprises given that the investment on R&D can fluctuate from year to year. Indeed the R&D expenses may be 'front-ended', and once the enterprise starts to monetise its innovation, after a lag of several years, the ratio may fall below the threshold. As such, if the ratio is assessed on an annual basis, the 15% HNTE incentive CIT rate may be lost at the point at which it would yield most benefit. To remedy this, in December 2017 the SAT clarified that the R&D expense ratio is to be calculated on a three-year rolling basis. This is clarified in the guidance on the annual CIT filing as a three-year look-back, and should facilitate greater access to the relief.

Extended life tax loss carry forwards for HNTEs: Innovation means uncertainty and potential failure, and the road from R&D effort to commercialised products takes time. Therefore, HNTEs can face a longer loss-making period than the general population of enterprises. Under the China CIT law, tax losses can be carried forward by an enterprise for five years at most. This may result in HNTE tax losses expiring before they can be offset against taxable profits. Caishui [2018] No. 76 (Circular 76) now extends the loss carry-forward period of HNTEs to 10 years. Furthermore, the 10-year carry forward is extended to losses incurred by a newly qualified HNTE in the five years before it qualified as a HNTE.

Further enhancements to the HNTE regime might be suggested, including:

Group-level HNTE application: As the existing HNTE rules apply on a separate legal entity basis, this can frustrate access to the incentive where R&D functions and sales are distributed across various entities in a corporate group. While the group as a whole might meet the HNTE qualifying criteria, no individual entity may meet all of the requirements. Enterprises are thus confronted with the decision to structure their operations in a manner which is not commercially optimal in order to access HNTE or forego the relief. Further, from a commercial perspective, the company which conducts the R&D function may not carry out material manufacturing activities. However, a pure R&D centre without a manufacturing function may not satisfy the existing HNTE rule in practice. In light of the fact that the R&D super deduction rules have already been adapted to the commercial realities of corporate groups (e.g. qualifying R&D expenses incurred within the group can be allocated among subsidiaries), it would not be unreasonable to suggest this thinking be extended to HNTE rules. Indeed, going beyond this, it would be desirable if China were to introduce general CIT group consolidation rules similar to those that exist in many advanced economies and facilitate business activity.

Expanding the HNTE incentive to all industries: One of the existing HNTE criteria is that the business of the applicant should fall into one of the encouraged categories of industries. The latest list was issued together with the latest administration rules for HNTE recognition in 2016. It includes eight industries: electronics and information technology, biology and new medicines, aerospace, new materials, high-tech services, new energy and energy-saving devices, resources and environmental protection, and advanced manufacturing and automation. Yet, the update to the encouraged categories is very slow. Given the manner in which new digital technologies, artificial intelligence (AI) and automation are driving an economy-wide transformation, cutting across all industries, such exclusion of many 'non-encouraged' sectors from HNTE appears to be a sub-optimal policy choice. A dynamic management of the encouraged categories should be established, or the incentive should be widened to all industries.

Expanding input VAT refund to HNTEs: In mid-2018, the China government designated the first batch of enterprises that are entitled to the refund of their carried-forward input VAT, which could only be carried forward indefinitely under the existing China VAT regime. The assessment of the eligibility to such VAT refund policy is mainly based on the industry in which the enterprise is engaged. Given that large upfront investments are very common for HNTEs which could result in high input VAT carry-forwards; if the VAT refund incentive could be granted to qualifying HNTEs, this would greatly improve the cash flow status of the HNTEs and consequently encourage re-investment by these HNTEs. The VAT refund incentive is just one example of the potential directional incentives that could be granted to HNTEs. If the governing authority could think outside the box, more directional incentives could be created to support the development of innovation.

Other measures and advice for taxpayers

Apart from the R&D bonus deduction incentive and the HNTE incentive, other innovation-related incentives will continue to be renewed or expanded in 2018. For example:

A substantial VC and angel investor IIT investment incentive was renewed, and extended nationwide in May 2018 (i.e. Caishui 2018 No. 55). Under this, qualifying investments made in science and technology enterprises, seeking capital or start-up stage support, can be partly offset against the taxable income of the investor; and

The incentive 15% CIT rate for ATSEs has been expanded nationwide from May 2018 (i.e. Caishui 2018 No. 44). This applies for both of the existing ATSE schemes, including the scheme for 'technically advanced service' providers, and the scheme for outsourcing enterprises.

These initiatives are clearly linked to the government's programme of fostering domestic mass innovation through seed capital, and fostering China's export of advanced services, particularly digital services, in which China already runs a trade surplus. For taxpayers to harness these incentives, and the other measures mentioned above, they should:

Review the group's development strategy, and consider which firm business activities or models may qualify as new and creative;

Keep a close eye on the latest refinements to tax incentives, and take them into consideration when planning new development projects; and

Seek expert advice on how to make the best use of the incentives.

Bin Yang |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner, Tax KPMG China 21 Floor, CTF Finance Center 6 Zhujiang East Road, Zhujiang New Town Guangzhou 510620, China Tel: +86 20 3813 8605 Bin Yang had 13 years of experience with the Department of Commerce, focusing on inbound investment policy advisory and investment project management. He then joined a multinational retailing company as the head of corporate development, legal and government affairs, and was responsible for providing professional opinions and services on development strategy, operational compliance and government affairs. Bin joined KPMG Guangzhou in 2006. He has extensive experience in corporate compliance and corporate structure advisory. Bin's clients include numerous eminent multinational enterprises, as well as small and medium size companies in retailing, manufacturing, real estate and service industries. Having extensive experience working with the government, Bin has in-depth knowledge with respect to the regulations governing both domestic and overseas companies, as well as corporate structures. With a sound understanding of the practical requirements of investment approval and management in major cities in mainland China, he has successfully assisted many overseas companies to establish subsidiaries/branches/representative offices in China. In addition, Bin has led many business and tax planning advisory projects for corporate restructuring, and the subsequent implementation tasks. Bin is the leader of the research and development (R&D) team of KPMG China. He has abundant experience in R&D services, including high and new-technology enterprise (HNTE) assessments, R&D expense super deductions, assisting clients in the development of R&D management systems and defending their HNTE status. As a key contact between KPMG and the government R&D department, Bin has maintained strong relationships and sound communication with related departments and provides advice on policy planning. Bin has an MBA. |

Benjamin Lu |

|

|---|---|

|

Director, Tax KPMG China 26th Floor, Plaza 66 Tower II 1266 Nanjing West Road Shanghai 200040, China Tel: +86 (21) 2212 3462 Benjamin, as the in-charge tax director on R&D related activities in central China, has rich experience in providing advisory and implementation services to various companies (including SOE, MNC and POE) across different industries. The assistance services include but are not limited to advice and assistance with bonus deduction on R&D expenses, assistance with HNTE application, assistance in ASTE application, etc. Benjamin has provided tax advisory and compliance services to a variety of clients relating to company setup, optimisation of transaction models, tax compliance and continuing operations, and has provided both tax due diligence and tax structuring advice on M&A and group restructuring transactions. Benjamin has rendered tax services to both multinational clients as well as domestic clients, and has an insightful view of the needs of the clients as well as China's tax regime and its practices. Benjamin has extensive experience in a wide range of industries including technology, media and telecommunications (TMT) (including digital economy, technology, media, etc.), consulting, industrial markets (including semi-conductor, chemical, automotive, etc.) and consumer markets. |

Liang Wu |

|

|---|---|

|

Senior Manager, Tax KPMG China 7th Floor, KPMG Tower, Oriental Plaza 1 East Chang An Avenue, Beijing Tel: +86 (10) 8508 7650 Liang Wu joined KPMG's Beijing office in 2015 and is a senior tax manager specialising in research and development (R&D) tax incentive services. He is the team leader of the R&D tax practice in northern China. Liang has extensive experience in delivering R&D tax incentive advisory and assistance to local clients in various sectors. His experience primarily includes assessing and identifying eligible R&D activities, tracking eligible R&D expenses, providing advisory for improving corporate R&D management procedures, sharing professional opinions in relevant policies and regulations, and assisting clients in seeking and implementing R&D tax incentive applications. Liang has a bachelor's degree in engineering. He is a chartered professional engineer and a member of the Institute of Engineers Australia. Prior to joining KPMG, Liang built a depth of experience in market study, engineering analysis and technical due diligence services in various industries. |