The telecommunications value chain has fundamentally evolved in a way that has altered the transfer pricing landscape for taxpayers, creating potential tax planning benefits but also potential pitfalls and exposures for taxpayers who have not realised that the nature and value of their related-party tangible, intangible, and service transactions have likely changed from even a few years ago.

In the past, telecom services meant fixed-line voice analog telephone services through copper wires; today voice services are provided through fixed lines, wireless, or voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) and the telecom service provider does not necessarily own the infrastructure necessary to provide the telecom services. One only needs to look at how integrated telecom service providers have expanded their service offerings around home security or even video, or the bundled price offerings for wired and wireless packages or a combined video, data, and phone service to see that the convergence around data and connectivity has shifted the potential value of intangible assets, as well as the potential risk associated with related-party transactions. In fact, from this integrated value chain perspective, integrated telecom service providers do not look that different from larger cable providers.

The complete value chain in telecommunications now includes providing connected and wireless solutions to residential and commercial customers, including prepaid wireless. The large telecom companies and their cable company competitors have integrated solutions along this complete value chain, allowing for bundled pricing of a greatly expanded portfolio of services often combining their own infrastructure with third-party-owned infrastructure to deliver the services. However, the telecom industry is distinct in that there are multiple companies that compete only in specific segments of the value chain. For example, infrastructure providers lease their capacity to wireless resellers and mobile virtual network operators, who focus their attention on gaining customers by selling their highly competitive services. Or VoIP competitors ride over the top of the infrastructure. This segmented nature of telecom provides transfer pricing insight into how arm's-length dealings may occur, and points to an indicative value for functions performed, risks borne, and assets employed in the industry.

We will review the current converged telecommunications value chain, paying particular attention to the value chain components that are often relevant for transfer pricing purposes. We will then explore some transfer pricing models that can be relevant for companies with related-party transactions competing in the telecom industry and discuss some considerations as to strengths and weaknesses of these transfer pricing models.

As we write this article AT&T has announced in a press release dated July 12, 2013 that it will acquire Leap Networks International Inc., subject to regulatory approval, in order to expand its prepaid wireless business and improve its spectrum position.

The telecom value chain

There are historically three core components of the value chain for a telecom company – network infrastructure, network operations (including maintenance and installation), and customer-facing sales and related support activities (such as billings, collections, and installation). Although these core telecom production elements have existed in some form from the late 1800s to the present day, there have been dramatic changes in the value chain components and a significant expansion in the value chain brought about by technology evolution and associated regulatory changes.

Value chain: Preconvergence

It may be hard for many millennial wireless customers to imagine the environment in which telecom became available in the late 19th century compared to just 30 years ago. Telecommunications services were provided through copper wire by American Telegraph and Telephone (AT&T), the sole company providing telecommunications services in the US through its network, which was incumbent on local exchange carriers. Similarly, in most countries around the world there was a single telecom provider, typically a government entity. As the sole provider of telecom services, AT&T sought to maximise profits by creating cost efficiencies by vertically integrating the key components of its value chain. In particular, the AT&T family of companies included entities focused on research and development (Bell Labs), the manufacture of equipment at both the infrastructure level (copper wire, switches) and the customer level (outlets, telephones) (Western Electric Company), and those focused on operating the infrastructure and technology used to transmit the voice or data services and interfacing with customers directly to selling services and provide customer support (the regional Bell operating companies).

As a provider of what was a necessary public utility, AT&T was able to predict with relative certainty the number of customers, and by extension its customer revenue. Within this historical value chain there was a relatively low emphasis on addressing specific customer preferences (that is, providing differentiated products) because the customer had only one provider from which to purchase the services. For example, AT&T strictly enforced policies against using telephone equipment by other manufacturers on its network. Because AT&T did not need to differentiate its services and invest in acquiring customers, it was not necessary for them to develop marketing intangibles and invest in customer acquisition in the same way telecom providers do today. In this pre-convergence environment, the "customer link" in the value chain was not the key link for AT&T, and AT&T accordingly placed greater emphasis on driving profits through, for example, its Bell Labs research and development activities and its Western Electric manufacturing activities (in addition to its significant product innovations, Western Electric was also a pioneer of Frederick Winslow Taylor's scientific management methods, which lead to manufacturing and cost efficiencies.

). That is not to say that the customer was unimportant to AT&T, but in a market where the customer is captive and there is only one service provider the value of customer and marketing intangibles would be expected to be different than in a market where those circumstance do not prevail.

Deregulation and technological change: Convergence

While AT&T competitors did enter the industry in the 1950s to 1970s, competition among telecommunications service providers did not begin in earnest until 1984 with the Department of Justice decision to break up AT&T and the 1996 Telecommunications Act. Hand in hand with the new regulatory environment came the rapid evolution of telephony technology based on both wireless transmission and the ability to transmit both voice and data through internet protocol in data packets. The telecom technology evolution is perhaps better characterised as revolutionary, as analog voice transmission over fixed lines and a closed network led to the rise of wireless voice and data transmission over open networks, often using internet protocol. These infrastructure technological developments were increasingly performed by third-party manufacturers that were now outside the integrated telecommunications ("Telco") services company value chain. And with increased competition to offer telecommunications and data services, the need to invest in marketing intangibles and acquire customers was much greater than in the preconvergence days of AT&T.

Convergence and the evolution of the value chain

With the rise of data services and the partial unbundling of infrastructure ownership from the provision of telecom services, along with the shift in the regulatory landscape (for example, the incumbent local exchange carriers were required to provide interconnects to competitive local exchange carriers and also offer unbundled services) the telecom industry became very competitive. As companies sought to retain or acquire customers and differentiate their service offerings, the nature and extent of intangible assets and risk profiles – both important considerations for transfer pricing – evolved. Access to the customer's premises through either the existing Telco's copper wire or the cable company's coaxial cable, along with the existing customer relationship, became a key competitive factor (customer premises access is often referred to as "the last mile" or "the last kilometer"). With a customer relationship and an existing physical network the traditional integrated Telco companies competed head to head with the integrated cable companies to sell a bundled portfolio of services that included video and internet in addition to phone or voice services. As customers began to rely less on the fixed line for these data, video, and phone services, the integrated providers could also offer wireless services to their bundled service offering (for example, Verizon and Comcast cross-sell each other's bundled network and entertainment services). Of course, competing against the integrated service providers are companies that offer prepaid wireless, VoIP, or video as a stand-alone offering.

Competition has also evolved so that there is delineated market customer segmentation between residential and commercial services, in part to reflect the difference in customer requirements in infrastructure and services. Double – and triple -play bundled service packages to residential customers now commonly include home security services, and communications to customers and targets about data services often include the speed of the wireless or wired internet. Telecommunications services specific to commercial customers existed in the pre-convergence era (dedicated lines, multiple lines, for example), but the differences between residential and commercial services tended to be differences in scale rather than function (of course, there was often a difference in the nature of telecom equipment leased by commercial customers). Today commercial customers are commonly offered a suite of various IT services that may be bundled with data analytics services and remote hosting services in addition to the telephone, infrastructure, and/or other data services.

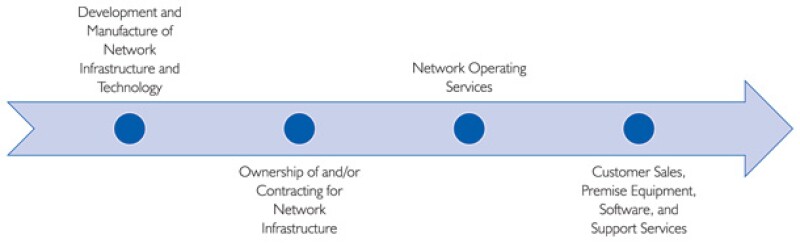

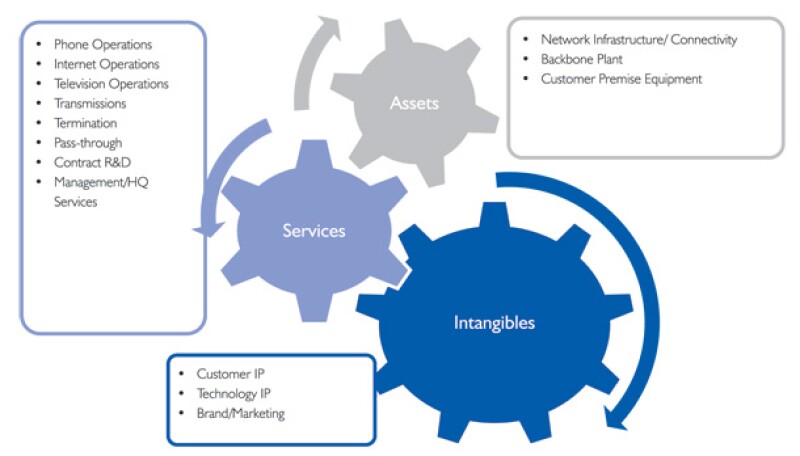

Before reviewing the transfer pricing components of the residential and commercial value chains, it is useful to take a step back for a big picture, generalised view of the telecom services value chain. At this generalised level, the key functions performed and assets employed in providing telecom services do not look markedly different for residential versus commercial services (see Diagram 1).

Diagram 1 |

|

Unlike the pre-convergence period, today there are disaggregated service providers that may compete at only a single link in the value chain. Also, infrastructure equipment development and manufacturing is no longer performed by the integrated telecom service providers. While integrated providers will almost certainly own significant infrastructure, it is also common for the integrated providers to contract with third parties for at least a portion of their network infrastructure footprint. Single-link market participants, such as prepaid wireless competitors, VoIP providers, and mobile virtual network operators may or may not own significant network infrastructure, and so may or may not face the economies of scale and the associated risks of utilising network capacity. However, the increased competition in the supply of telecom services has in some cases dramatically increased the fixed costs and risks associated with acquiring customers, leading to economies of scale benefits at the customer sales side of the value chain. The bundling of telecom services to both residential and commercial customers using double-play and triple-play pricing is one means of taking advantage of an existing customer relationship and to offset the customer acquisition costs to some degree.

Residential value chain – Integrated service providers

The incumbent cable service providers, already equipped with key links in the evolved telecommunications value chain – physical network assets, existing network technology, organisations to operate the networks and a strong customer base – as well as the resources to develop technologies specific to voice services, took advantage of the opportunity to enter into the market as integrated providers of telecommunications services. Through substantial capital investments in modifying physical networks and related technology to handle the provision of voice services, and through its efforts to deploy new and innovative services to existing video consumers, often through bundled service offerings, the entry of cable companies into this industry as integrated services providers and the establishment of these companies as core market participants has facilitated the development of a highly competitive market for residential telecommunications services. Just two decades after enactment of the Telecommunications Act, cable television providers now make up five of the top 10 residential phone companies in the country. And this is not unique to the US. On June 24, 2013 Vodafone announced that it was buying the German cable operator Kabel Deutschland for 7.7 billion euros, or $10.1 billion.

The bundling of telecommunications services with video services was a successful method for motivating users of telecommunications services to switch from their historical telecommunications services provider as bundling reduced the transaction costs for procuring the portfolio of services. For example, customers could buy a double play or triple play bundle, paying a flat rate for all three services on one bill. In addition to attracting new customers, bundling is also a strategy for reducing customer turnover (churn) as it mitigates the risk of customers switching service providers. Essentially, the bundling approach attracts the customer and then creates "customer stickiness" once the customer begins to rely on the bundled services. The practice of attracting customers through bundling services was not new to the Telco industry, in which voice and data services had historically been sold together to customers, and Telco companies quickly launched their own video service offerings (AT&T U-verse, Verizon FiOS) to remain competitive. Some industry participants have questioned how significant video services may be for the integrated service providers in the long run. For example, the Wall Street Journal reported in its April 5, 2013 edition that James Dolan, Cablevision Systems Corp. CEO, stated in an interview "…that 'there could come a day' when Cablevision stops offering television service…"

The strategy of adding additional services to the bundle to potentially gain market share and further strengthen the customer relationship continues to be observed after the initial bundling of video with data and voice services. In the past few years, for example, integrated services providers have begun to offer a full spectrum of home management services (home security, remote management of lights, HVAC control, leak detection, etc.). More recently, as the population embraces mobile wireless devices, integrated service providers have also sought to include wireless voice and data services in the bundle. The trending use of mobile wireless technology is so marked that industry participants are investing more heavily to develop innovative new mobile technology service offerings that go beyond the capabilities of smartphones and tablets. AT&T, for example, announced in June 2013 that it is opening two new innovation centers, one focused on residential services and a second focused on commercial services, and will invest $14 billion over the next three years to develop cutting edge wireless services.

Residential value chain – Disaggregated service providers

The transition from a market dominated by a vertically integrated sole supplier to a competitive environment has created myriad opportunities for enterprises to enter into the Telco industry with a specialised focus on a single link within the value chain. For example, consumers can purchase digital media receivers (DMR) to access video content from the internet. And VoIP service providers such as Vonage and Skype provide service offerings focusing directly on customer facing interaction. These services are provided "over the top" of third-party infrastructure and therefore the core element of the value chain for a VoIP or DMR enterprise is to develop customer-facing technology and most importantly to attract customers, often by providing services at a lower cost than the integrated providers. Given that these over the top providers do not offer internet services in their bundle, they must engage in aggressive pricing and allocate a higher percentage of total costs toward marketing efforts relative to integrated providers to drive service revenue (VoIP providers have historically allocated 25% or more of their total budgeted costs to marketing efforts, whereas integrated providers have historically allocated less than 10% of budgeted costs toward marketing efforts). At the other end of the value chain, companies such as Level 3 and Qwest entered the market with the goal of developing the physical network. Developing infrastructure is extremely capital intensive and risky, with decisions regarding capital investments based on the anticipated use of such investments over the long term. Companies operating in this space are able to gain competitive advantage and drive profits by having a relatively cheap cost of capital and establishing an expansive footprint that enables customers to come to a single infrastructure provider to purchase access to infrastructure in geographically diverse locations or even globally. Other companies sought to focus on the development of technology that enables the infrastructure, such as software and other classes of intangible property that optimise the use of physical network equipment. The focus of those companies is to attract and retain innovative and commercial professionals that can identify, develop, and commercialise technologies. As is the case with many research and development organisations, this type of enterprise will often incur development costs with little or no revenue while products or services are still under development.

Commercial value chain – Integrated service providers

In principle, the value chain for commercial telecommunications services in the converged environment is similar to the value chain for residential services described above (sending data packets from point A to point B though network infrastructure and technology, with services provided by a network operator and technology to interface the transferred data packets). That said, there are clear differences. For example, while both residential and commercial customers are interested in purchasing reliable, clear phone service, commercial customers may also seek service providers that can provide online voicemail and network security services, mobile network access, and integrate traditional voice-only services with Microsoft tools such as Outlook, SharePoint, and Messenger. Further, commercial customers generally consider reliability and speed of data services more important than residential customers, which has forced many service providers to upgrade their networks so they can provide faster and more reliable data service to commercial customers.

Companies within this segment of the Telco industry also seek to bundle products to attract customers and reduce churn; however, the bundle of services varies from what is offered commonly to residential customers. Commercial customers are more focused on purchasing telecommunications services from providers of fully integrated suppliers of IT solutions that bundle voice and data services with complementary services and customers are increasingly demanding that many of these services be provided through the cloud to reduce capital expenditures and shorten the timeline for receiving the services. Commercial customers also have a higher propensity to demand the latest technology, and integrated services providers must continuously innovate and develop new services to add to their bundle of services to successfully win and retain market share in the commercial services segment.

Commercial value chain – Disaggregated service providers

Similar to disaggregated residential services, the commercial segment of the Telco industry has seen the emergence of companies that specialise in providing services that target one link of the overall value chain. VoIP service providers that provide service offerings focusing directly on customer facing interaction are also common in the commercial services segment, with specialised bundled service offerings that incorporate the complementary services offered by integrated service providers described above. There is also a place for companies specialising in infrastructure services, network operations, and the development of software that optimises the use of the physical infrastructure and enables specific customer facing services (such as Cisco's WebEx webcast services offering that integrate voice, data and video services with a customer's incumbent IT systems). More specific to the commercial services segment, however, is the large number disaggregated service providers ranging from large established companies to startups that focus on the provision of cloud services, including software-as-a-service offerings, platform-as-a-service and infrastructure-as-a-service product offerings, as well as hosting companies specialising in remote hosting of webpages, storage of immense amounts of enterprise data, and performing analytics on such data. In many cases, these hosting companies provide services primarily through the cloud.

Transfer pricing and the telecom value chain

From the previous discussion it is easy to see that the nature and extent of tangible, intangible, and services transactions that are relevant to transfer pricing have evolved. In this section, we review transfer pricing models that are potentially relevant to telecom service transactions.

Finding the profit in telecom – risks and return to IP ownership

Compared to the pre-convergence period, the value of customer and marketing intangibles is generally higher, while technology development has predominantly migrated to third-party infrastructure manufacturers. In evaluating return to IP ownership, we will distinguish ownership of IP between legal ownership and economic ownership, since in many instances economic and legal ownership of property can be separated for transfer pricing purposes.

Economic ownership of IP is a subset of the property rights generally associated with legal ownership of intangibles. In transfer pricing, economic ownership of intangible property tends to be most relevant, because it is the economic owner of intangible property that has the right to receive the income associated with the intangibles. The determination of economic ownership for the right to receive income associated with valuable intangibles is fact-specific and depends on the following four key factors:

Funding the development of the intangibles

Bearing the risks of success or failure of the intangible development

Performing the development functions and activities

Employing the personnel that make key decisions regarding the intangible developments

While the importance of each of these four factors to the determination of economic ownership of intangibles is fact-specific, employing the personnel that make the significant decisions and bearing the risk of intangible development success and failure tend to be the most important determinants of economic ownership in many cases. So, for example, the legal entity that incurs the expenses and employs the relevant personnel responsible for acquiring customers for mobile virtual network operator or VoIP provider may be regarded as the economic owner of any marketing and customer list intangibles and so may need to be compensated by related parties that are using these intangibles to sell the services. This transfer pricing concept of economic ownership could also suggest that the customer and marketing intangible profit reward associated with bundled double play or triple-play product pricing or the sale of security or hosting services could rest with a legal entity that is not providing the security, hosting, or some of the –bundled services. That is, there could be a legal entity in the value chain that economically owns the customer and marketing intangibles apart from the legal entity providing, for example, home security or video services.

Another important concept in transfer pricing associated with arm's-length behavior is risk and the potential profit reward for bearing that risk, separate from the risk associated with the development of valuable intangible property. For example, infrastructure providers that own network infrastructure or telecom companies that commit to a fixed amount capacity usage have capacity risk associated with the utilisation of the physical network (For example, Indefeasible Rights of Use (IRUs) are common in telecom. An IRU is the right to use a fixed amount of communications capacity, or a certain communications facility, for a defined period of time). This capacity risk may be contractually borne by a legal entity other than the one that has the legal ownership rights of the physical assets or has committed to the capacity utilisation. Moving capacity utilisation risk means that relevant legal entities within the value chain are protected from losses or large movement in profits directly associated with network capacity utilisation, while the entity bearing the capacity risk may see its profit potential rise and fall as capacity utilisation rises or falls. For example, the entity bearing capacity utilisation risk could pay a guaranteed cost plus profit or a risk-adjusted return on assets level of profit to the entities that are protected from the capacity risk.

Transfer pricing models relevant to telecom

Much of the telecom value chain involves a network, most obviously the physical infrastructure network. Network models relevant to telecom reflect the fact that there may be multiple legal entities owning or utilising tangible, intangible, and capital assets and potentially collecting revenues that include the value of these tangible, intangible, and capital assets. Since the profit reward for intangibles, risk bearing, and value creation needs to be recognised at the legal entity regarded as the economic owner, risk bearer, and/or value creator, transfer pricing network models involve the planning or determination of pricing or profit flows such that the level of taxable income reported in an entity is consistent with its contributions in generating the relevant profits. The most common type of transfer pricing network model is called the profit split model.

Decentralised intangible ownership – Profit split model

A profit split transfer pricing model could be used to determine the split of the system profit when, for example, customer and marketing intangibles are used in a telecom service and are economically owned by more than one legal entity. Under a profit split model, a profit return and associated expenses for routine activities (billing/invoicing, installation and maintenance, the provision of infrastructure) is deducted from net revenue so that the remaining revenue is the residual revenue or gross profit associated with the intangibles employed to generate the system profit. This intangible residual revenue is then split between the intangibles owners based on factors that indicate the contribution of the intangible to the earning of the residual revenue or gross profit.

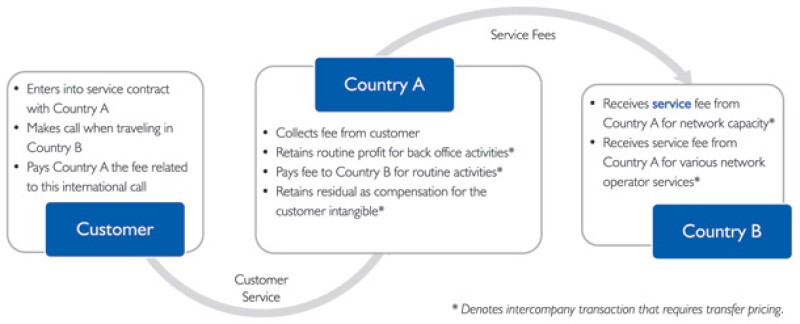

For example, consider a wireless virtual network operator that has an international footprint and provides its services in two countries, with customers that travel between the two countries. The legal entities in each of the two countries engage in local marketing activities to solicit, acquire, and retain customers, contract with third parties locally for network capacity, and perform the services necessary to operate the wireless virtual network. In this fact pattern, the purchase of network infrastructure and provision of network operator and back office services are activities that generate routine profit and the sales and marketing activities performed to attract and retain customers generate the intangible profit (As indicated before, there may be risks associated with a commitment to use contracted network capacity that potentially should be compensated as part of the routine profit.) Taking into account that the local legal entities bore the expenses and associated risk to develop the customer base, the profit split method would suggest the above transfer pricing system for allocating the revenues/profits earned by the enterprise from a phone call made by an individual customer from Country A when traveling in Country B.

The transaction and financial flows are easy to see in the above model because the example involves one individual customer. But the full year financial statements for both the Country A entity and the Country B entity reflect commingled revenues and costs due to the fact that Country A customers travelled to Country B and utilised the infrastructure of the Country B legal entity, while Country B customers travelled to Country A and utilised the infrastructure of the Country A entity. The profit split would proceed by measuring the combined system revenues and costs of both the Country A and Country B legal entities, rewarding their routine activities by reimbursing their costs plus the appropriate routine profits and splitting the revenue remaining after deducting these routine reimbursements based on the relative value of the customers that they contribute to the business. In this simple example we assume that the pricing to customers and intangible development costs and risks in both Country A and Country B are the same and the relative value of the customers in generating intangible profit is equivalent in both countries.

While the example above is simplistic, in practice a profit split model involving multiple legal entity ownership of valuable intangibles is a relatively sophisticated and complex transfer pricing system. For example, the determination of arm's-length transfer prices for each of the intercompany transactions identified in Diagram 2 with an asterisk could involve a degree of complexity. One approach to simplifying the transfer pricing system is to concentrate the intangible property ownership and potentially some risks in a hub or entrepreneurial company through a model that is often referred to as a hub-and-spoke transfer pricing system.

Diagram 2 |

|

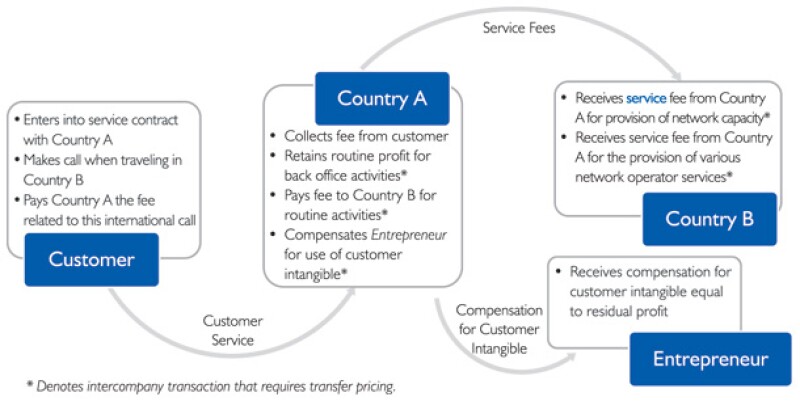

Centralised intangible ownership – Hub-and-spoke model

In some cases, providers of telecommunications services choose to centralise the development of core intangible property for reasons such as achieving economies of scale, optimising resource allocation, and managing risk. In this type of hub-and-spoke business model, the legal entity developing the core intangible property regarded as the economic owner of the resulting intangible property incurs all development costs, has employees making the significant intangible development decisions, and incurs the associated risks in creating the intangible property. This entrepreneurial entity will then provide the developed intangible property to its related parties for use in their local markets, in return for compensation reflecting the arm's-length nature of the value in the local market of the intangible property provided.

For example, one area in which sellers of telecom services may seek to centralise their efforts is in the development of global marketing strategies, including the funding of the creation and design of advertising and promotional campaigns as well as the development of pricing tools and other relevant software for use by the local entities. Using the example introduced above, we now assume the local entities in Country A and Country B perform only routine sales and marketing activities to execute the marketing strategy established by a new entity we introduce called the "Entrepreneur". The Entrepreneur performs the functions and bears the risks associated with the global marketing strategies, whereas the Country A and Country B local entities perform routine marketing execution activities such as distribution of marketing materials to customers, placement of advertisements in media outlets, etc. The Entrepreneur is the economic owner of the profits associated with the marketing intangibles and so would need to be compensated out of the revenues embodying these intangibles collected by the Country A and Country B local entities. Again viewing the transaction flows from an individual customer perspective, the legal entity in Country A would need to pay the Entrepreneur for its use of the Entrepreneur's marketing intangibles, which are embedded in the revenue that the Country A legal entity collects from the Country A customer, regardless of whether the customer makes a call in Country A or Country B.

The full year revenues in the financial statements for both the Country A entity and the Country B entity would reflect the value of the use of and revenue benefit from the Entrepreneur's marketing intangibles. Thus, the legal entities in Country A and Country B would need to pay Entrepreneur the arm's-length amount of the local value of the Entrepreneur's marketing intangibles. In this simple model, Country A and Country B receive the costs and profit reimbursements reflecting the routine nature of their value chain contributions, while the complete residual revenue or profit is paid to the Entrepreneur. The arm's-length transfer prices required for this example of the hub-and-spoke model on an individual customer transaction level is identified in Diagram 3 with an asterisk; in general, a transfer pricing system designed under the hub-and-spoke concept is easier to administer than a profit split model.

Diagram 3 |

|

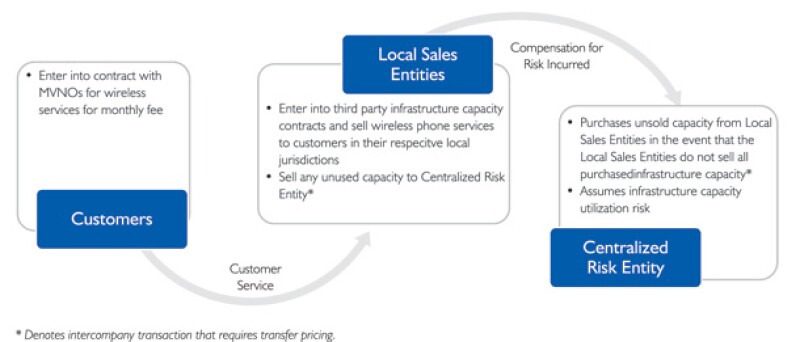

Concentrating risk bearing through transfer pricing

Although overall business risks cannot be mitigated through transfer pricing, the concentration of certain risks within one legal entity can often be accomplished through transfer pricing planning. Concentrating risks within a legal entity potentially has many benefits, including simplifying a transfer pricing system, determining that potential tax losses associated with negative risk events is not dispersed over legal entities in many countries, and improving the expected taxable income in a legal entity that bears the risk. For example, a mobile virtual network operator providing wireless telecom services in several countries where the legal entity in the country locally contracts for network capacity from third-party infrastructure capacity providers. To the extent the infrastructure capacity contracts require the mobile virtual network operator to commit to the use of a specified amount of infrastructure capacity, the mobile virtual network operator faces infrastructure capacity utilisation risk in each of its local legal entities where such contracts are concluded. To concentrate this capacity utilisation risk in one entity, the risk-bearing entity can provide a guarantee to the other local entities entering into infrastructure capacity contracts against bearing expenses associated with underutilised network capacity. The risk-bearing entity would need to receive a profit risk premium for bearing the infrastructure capacity utilisation risk (see Diagram 4).

Diagram 4 |

|

For integrated service providers and disaggregated services providers alike, the strategy to concentrate risk in a particular entity may provide opportunities to concentrate functions or assets as well. For example, the risk-bearing entity could also perform central negotiations of all infrastructure contracts and potentially take advantage of the pricing benefits that may be associated with scale purchases of infrastructure capacity or other products or services. In general, by separating the financial risks and key strategic decision-making roles from the roles involved in executing the established strategy, an enterprise can isolate and enjoy benefits from locating the economic ownership of a given class of intangible property in an entity other than that which performs the majority of the development activities.

Identifying the intangible versus routine contributions in a bundled pricing model

As discussed in detail above, telecom services providers regularly bundle their telecom voice services with other complementary services to attract customers and reduce customer churn. On the residential customer side, triple-play pricing may include combinations of internet, video, fixed line phone, home security, or wireless phone. On the commercial side phone, data, IT services, and internet infrastructure are commonly offered as combined pricing. The offered services that are priced in combination within the bundle are not equally valuable from a transfer pricing value chain perspective, which introduces the possibility to use transfer pricing to determine the contributions by the legal entities providing the components of the bundled services. For example, some legal entities within the value chain may perform routine activities in support of the provision of the bundled service offering, while other legal entities may contribute valuable intangible property. Transfer pricing principles are relevant to determining the pricing or profit reward that is attributable to the value chain components contributed by entities providing services with the bundled pricing packages.

Diagram 5 outlines at a high level the types of services, assets, and intangibles common to telecom services providers providing a product bundle that includes phone, internet, video, and home security services.

Diagram 5 |

|

As suggested by the graph above, crucial to the design of a transfer pricing model that involves bundled pricing of services is the ability to identify the core intangible property that drives the revenues associated with the offers of bundled services; for some companies, it is the existing customer relationships that drive the offer of bundled services. As is the case in other transfer pricing models, key intangibles utilised to sell services to customers are not always economically owned by the legal entity providing the customer facing telecom services and booking the customer revenue. Transfer pricing principles under the arm's-length standard provide a very effective approach to determine the value of the contributions by related parties within the value chain.

Potential change

The convergence of the telecom services value chain with the associated bundling of telecom services to customers has potentially changed the nature and value of related-party transactions involving services, intangibles, and tangibles property. These shifting transactions and continued convergence have also impacted at least some business risks of related parties competing along the value chain. Specifically, the value of customer and marketing intangibles have increased for some market participants as the ability to offer double and triple play bundled pricing creates customer stickiness and potentially enhances the scale benefits associated with the high fixed costs of telecom infrastructure. There are various transfer pricing models that can help taxpayers deal with the continued convergence in telecom to address the specific facts and circumstances of the business.

Biography |

||

|

|

Peter Meenan Principal, Transfer Pricing Deloitte Tax LLP Tel: +1 404 220 1354 Email: pmeenan@deloitte.com Experience Dr. Peter Meenan is the Managing Principal in Deloitte Tax's Southeast Transfer Pricing practice and is Deloitte Tax's Transfer Pricing industry leader for the telecommunications industry. Dr. Meenan has 20 years of transfer pricing experience with Deloitte Tax. In addition to practicing transfer pricing in Deloitte Tax's Northeast and Southeast US regions, he has significant international transfer pricing experience. Dr. Meenan was on the European leadership committee and a founding member of Deloitte's European Transfer Pricing Practices during his seven year assignment with both Deloitte UK and Deloitte Germany. He also served as Deloitte's senior transfer pricing economist in Asia and co-leader of the Japanese transfer pricing practice during his four year assignment in Deloitte Tokyo. Dr. Meenan has significant transfer pricing experience advising companies competing in the telecommunications, media, and technology industries in areas that include transfer pricing planning and implementation, audit defense, transfer pricing documentation, and advance pricing agreements and international arbitration procedures. He is a frequent speaker and an author on valuation and transfer pricing. Dr. Meenan developed Deloitte's pan-European and pan-Asian internal transfer pricing training courses while on assignment in these regions. Dr. Meenan has also been a consultant and a trainer for the tax authorities in the Czech Republic, Denmark, Malaysia, and Vietnam on transfer pricing matters. Dr. Meenan received his Ph.D. in Economics from Purdue University and is a Chartered Financial Analyst. He has been voted on numerous occasions as a World's Leading Tax Adviser by International Tax Review and a World's Leading Transfer Pricing Advisor by Euromoney. |

Biography |

||

|

|

Ben Miller Manager Deloitte Tax LLP Tel: +1 404 631 3730 Email: bemiller@deloitte.com Experience Ben Miller is a senior manager in the transfer pricing practice of Deloitte Tax. Ben has worked with numerous US domestic and multinational firms and foreign-based companies with US subsidiaries to evaluate the transfer prices of tangible goods, intangible property, financial services (e.g., loans and guarantees) and cost sharing transactions for various purposes, including 6662 penalty protection, planning, international supply chain restructuring, advance pricing agreements, preparation and implementation of audit defense, due diligence for mergers/acquisitions, and Section 199 purposes. Ben earned his Ph.D. in economics from Georgia State University in 2008, with a focus in labour economics and public finance. Ben's research has been published in the Industrial and Labor Relations Review. |