Words taken out of context, even in day-to-day life, often result in misunderstandings, and understanding the context of the words becomes paramount. In legal parlance, this is even more imperative, lest the meaning undergo a radical shift.

International agreements drafted by diplomats (e.g., tax treaties, or TTs), unlike domestic tax laws, are often devoid of legal and precise phraseology and are prone to varied interpretations. TTs generally define certain terms and provide a recourse to domestic law for undefined terms “unless the context otherwise requires”. What constitutes context and when it requires otherwise is a litmus test, and the interplay between treaty and domestic law interpretation is a critical aspect of international tax jurisprudence.

Tax treaty interpretation

TTs, which are designed to facilitate economic relations between countries, attempt to avoid problems arising from double taxation. Treaty interpretation involves a process to derive the meaning of the words in question by looking at the language used and the intentions of the parties (see Her Majesty The Queen v Crown Forest Industries Limited et al, Supreme Court of Canada, 1995). Contrary to an ordinary taxing statute, a TT must be liberally interpreted, with a view to achieving its underlying purpose (see United States v Stuart, US Supreme Court, 1989). Courts in Canada (see JN Gladden Estate v The Queen, Federal Court Trial Division, 1985) and the US (see Bacardi Corporation of America v Domenech, US Supreme Court, 1940) have observed that a literal or legalistic interpretation must be avoided if the basic object of the treaty might be defeated or frustrated.

In Union of India and Anr v Azadi Bachao Andolan and Anr (2003), the Indian Supreme Court also acknowledged that the principles adopted in treaty interpretation are not the same as in the interpretation of statutory legislation, as the interpreter is often required to cope with a disorganised composition, given that the drafting of treaties is notoriously sloppy. The interpretation of TTs, being creatures of diplomatic negotiations, must thus be purposive, and the meaning attributed to treaty provisions by the respective negotiating parties thereto, though not conclusive, is entitled to great weight (see Sumitomo Shoji America, Inc. v Avagliano, US Supreme Court, 1982; and Thomson v Thomson, Supreme Court of Canada, 1994).

The Vienna Convention

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), a universal guideline on treaty interpretation, emphasises interpretation of treaties in good faith and with ordinary meanings being ascribed to their words. Treaty interpretation comprises the overall scheme of the treaty (treaty text, preamble, supplementary means of interpretation; e.g., the OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital and its commentaries, or the MTC). The VCLT also provides that a treaty must be interpreted based on its own terms and without reference to domestic law. Although India is not a signatory to the VCLT, the Supreme Court of India has upheld the VCLT’s treaty interpretation principles (see Ram Jethmalani and Ors v Union of India and Ors, 2011).

Context: qualification

Though the VCLT discourages the use of domestic law in treaty interpretation, the MTC, a well-recognised supplementary means of interpretation, allows the pursuit of domestic law for undefined treaty terms. However, the interpretation of a treaty term based on a meaning used under domestic law can cause the following ‘qualification’ conflicts in international tax law (see “Fowler Case: domestic law and treaty interpretation”, Luís Eduardo Schoueri and Renan Baleeiro Costa, in Taxes Crossing Borders (and Tax Professors Too), Liber Amicorum Prof Dr RG Prokisch):

Lex fori (each state qualifies a treaty term in accordance with its domestic law) – this may, though, result in a distortive application of the treaty.

Lex causae (both states adopt the same ‘qualification’ in accordance with the domestic law of the source state) – this may give the source state the ability to broaden the scope of treaty terms by altering its domestic law.

Autonomous qualification (both states endeavour to reach the same qualification as required by the context of the treaty) – although the aim is to derive a common qualification from the context, finding context from the intention of the parties during a negotiation process is a difficult endeavour in practice as most countries (including India) rarely publish treaty negotiation documents or understandings derived from the negotiations. Where the basis to adopt an autonomous approach exists, courts proceed with the same, and domestic law may then not be resorted to.

In the absence of an autonomous interpretation, though, courts resort to a lex fori or lex causae approach. Thus, recourse to domestic law is not a right but, rather, a last recourse.

Domestic tax law/general law

Article 3(2) of the MTC provides for recourse not only to domestic tax law but also to “other laws of that State” for finding the meaning of an undefined term in a treaty. Recent TTs entered into by India (e.g., those with Mexico and Hong Kong) adopt a similar recourse to domestic laws, in contrast to many earlier TTs, which provided for a restricted recourse to domestic tax law (e.g., the treaties with Australia, Germany, France, and the UK), in accordance with the MTC before the 1995 update.

Interestingly, the Supreme Court of India, in Engineering Analysis Centre of Excellence Private Limited v Commissioner of Income Tax (2021), extensively dealt with Indian copyright law in a landmark decision on the taxation of “off-the-shelf software”, despite Article 3(2) of the relevant TT (with the US) restricting recourse to domestic tax law. The court directly adopted supplementary means of interpretation and domestic law without addressing the context. It followed the High Court of Australia’s ruling in Thiel v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1990), which underscored the importance of the VCLT and recourse to supplementary means of interpretation, and the UK Supreme Court, which observed in Fowler (Respondent) v Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (2020) that terms undefined in a treaty or in tax law shall have meaning under the general law of the source state. It is important to note that the UK Supreme Court dealt with a TT between the UK and South Africa that allows recourse to domestic laws as against domestic tax laws.

Context: domestic law

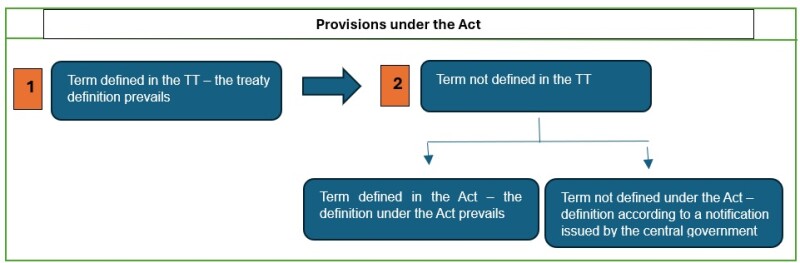

The Indian Income-tax Act, 1961 (the Act) provides a mechanism for the interpretation of terms not defined under a TT, as illustrated in the diagram below.

The Act permits the adoption of the meaning provided in it for an undefined term in a TT and in the absence thereof, the meaning under a notification issued by the central government. In the context of a TT (especially one that provides for recourse only to domestic tax law), a notification issued is not a domestic tax law and, hence, a reference to such domestic laws would essentially go beyond domestic tax law.

The Income-tax Bill, 2025 (the 2025 Bill) adds complexity and provides for recourse to other central laws in case any term remains undefined even after following the above-described statutory mechanism. This approach may not be consistent with the context of Article 3(2), and is squarely contrary to the purposive approach for treaty interpretation as postulated in the VCLT, but seeks to indirectly recognise the 2017 version of Article 3(2) in existing TTs.

In Maharashtra State Electricity Board v Joint Commissioner of Income Tax (2001), the Mumbai Income Tax Appellate Tribunal – while addressing the question of ‘what is context’ under the provisions of the definitions clause in the Act – observed that “[t]ext and context are the basis of interpretation [and] [n]either can be ignored. […] That interpretation is best which makes the textual interpretation match the contextual. A statute is best interpreted when we know why it was enacted.”

Essentially, thus, the interpretation “should not only be not repugnant to the context [but rather one that] would aid the achievement of the purpose” (KV Muthu v Angamuthu Ammal, Supreme Court of India, 1996), which is derived from:

The subtext of the statute (Commissioner of Expenditure-Tax, Gujarat, Ahmedabad v Darshan Surendra Parekh, Supreme Court of India, 1967; and National Insurance Company Limited and Anr v Kirpal Singh, Supreme Court of India, 2014);

The nature of the subject matter; and

The intention of the author (Dy. Chief Controller of Imports & Exports, New Delhi v KT Kosalram & Ors, Supreme Court of India, 1970; and Commissioner Of Income-Tax, Bombay v Smt. Indira Balkrishna, Supreme Court of India, 1960).

Although the interpretation of a statute is different from that of a TT, the jurisprudence on the term ‘unless context provides otherwise’ draws certain parallels.

Parting thoughts

A common thread from the jurisprudence indicates that the concept of context in international tax law and as recognised under Indian jurisprudence largely provides the following:

While interpreting context in a TT, due recognition should be given to the fact that TTs need to be liberally interpreted, being a creature of negotiation by diplomats, unlike statutes drafted by legal craftsmen. Thus, the intention of the parties negotiating the treaty should be given primacy.

“Context” includes the overall scheme of the treaty/statute, including the preamble, the ordinary meaning of the words, treaty practice, and subsequent agreements between countries.

In the event that the ordinary meaning of the words leads to absurd results and other primary mechanisms fail, the domestic tax law meaning will be given effect under Article 3(2) of the TT.

Due regard to the wording of Article 3(2) of the TTs will be given to ensure that recourse is made to domestic tax law or “any law”. If the term is not defined in domestic tax law and no other meaning can be attributed to determine the context, other relevant domestic law may be relied upon.