One of the key features of the Dutch corporate income tax regime is its fiscal unity regime. Dutch tax resident companies that opt to be included in a fiscal unity are generally treated as one taxpayer for Dutch corporate income tax purposes.

As a result of the fiscal unity, the results of the companies of the fiscal unity can be set off against each other. Transactions within the fiscal unity (e.g. sale of assets or post acquisition reorganisations) are further not recognised for Dutch corporate income tax purposes and can therefore take place on a tax neutral basis.

The compatibility of the fiscal unity regime with EU law (freedom of establishment) has been tested in recent years as the advantages of the fiscal unity regime only apply in domestic situations. Following a ruling from European Court of Justice (judgment of February 22 2018, X BV and X NV v Staatssecretaris van Financiën, Joined Cases C-398/16 and C-399/16, ECLI:EU:C:2018:110) and legislative changes to address the incompatibility of the regime with EU law, the fiscal unity regime is per January 1 2018 deemed not to exist for the purpose of certain specific rules of Dutch tax legislation (there will be no further elaborate on these specific rules in the article. Also, anti-abuse provisions may apply at the moment of termination of the fiscal unity).

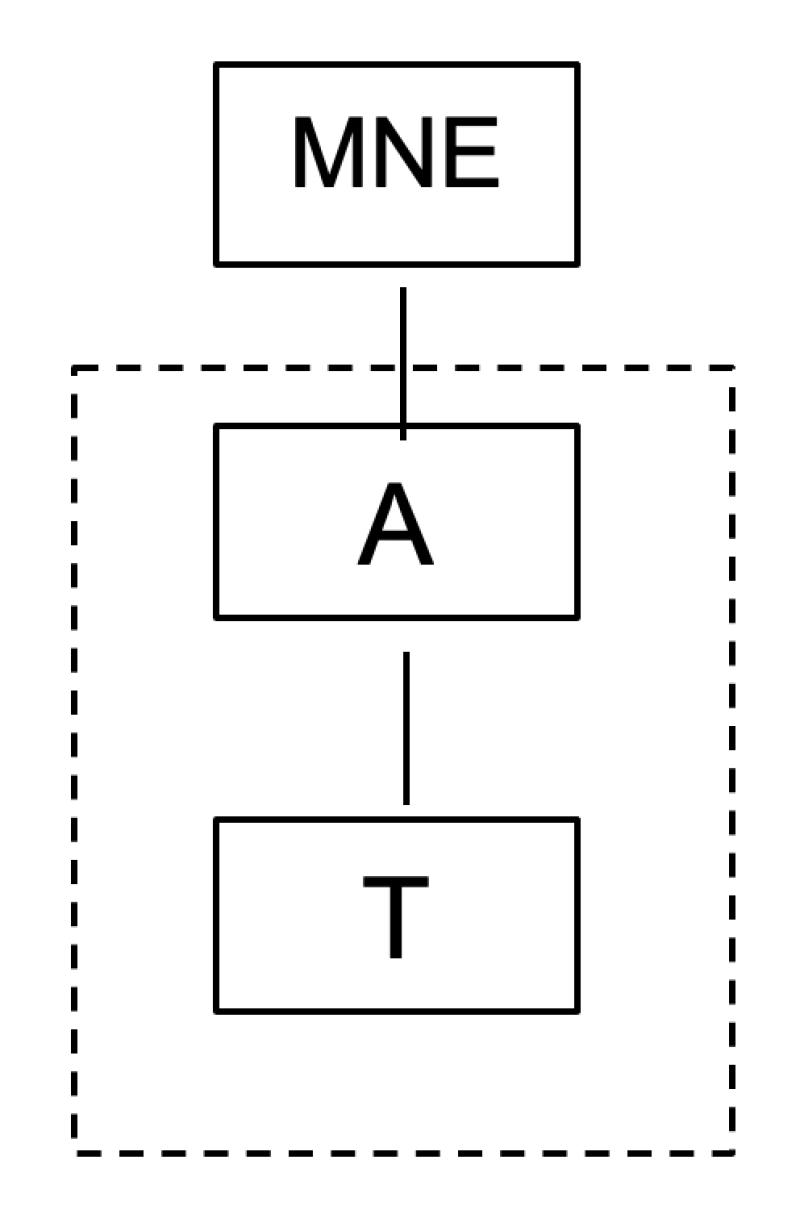

The application of the fiscal unity regime is often considered when an acquisition takes place via share deal. If a Dutch tax resident company (A) acquires at least 95% of the share capital of Dutch tax resident target company (T), A and T can in principle form a fiscal unity for Dutch corporate income tax purposes (specific exceptions apply in which case a fiscal unity cannot be formed. The forming of a fiscal unity can trigger corporate income tax charges in the year in which the fiscal unity is formed. There will be no further elaboration on these topics in the article).

A specific advantage of this structure could be that in case the financing costs of the acquisition exceeds the profits of A, the financing costs could be set off against the profits of A and T together. A limitation of this benefit may however be that the Netherlands have included various rules in its tax legislation on the basis of which the deduction of financing costs could be denied, including recent measures implemented as a result of the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD 1 and ATAD 2).

Per January 1 2019, the Netherland implemented the so-called earning stripping rules from ATAD 1. The rules currently limit the deduction of interest costs for as far as it exceeds the interest income to the highest of:

20% of the tax EBITDA; or

€1 million.

Interest expenses that cannot be deducted on the basis of the earning stripping rules can be carried forward to the next year. When a fiscal unity is formed between A and T, the earning stripping rules apply on a fiscal unity level. This means that the consolidated EBITDA of A and T can be used to determine the amount of non-deductible interest expenses.

On the other hand, the €1 million threshold can only be applied once. If A and T would not form a fiscal unity, both companies can deduct interest expenses up to €1 million without any limitations under the earning stripping rules. In practice holding companies generally do not have significant stand-alone earnings to offset the financing costs to in any case, which has as a result that the limit of €1 million would not significantly impact the threshold at fiscal unity level.

Tax rates

A slight disadvantage of the fiscal unity could be that there are two corporate income tax brackets. The lower corporate tax rate of 15% is applicable to taxable income up to €395,000. The lower rate can in principle be applied by each taxpayer. At fiscal unity level, the lower rate can only be applied up to €395,000 as well. A fiscal unity could therefore result in additional corporate income tax burden of €43,000 (25.8% -/- 15% * €395,000). As noted, however, most holding companies are generally not affected by this, since they have limited stand-alone income and therefore do not significantly affect the total taxable amount at fiscal unity level.

Future of the fiscal unity regime

As a result of the continuous uncertainty on the compatibility of the regime with EU law, the Dutch government is considering replacing the fiscal unity regime with a new regime where profits and/or losses can be transferred.

An important difference between these regimes is that transactions between the companies applying the new regime will be recognised for corporate income tax purposes. This means that tax neutral reorganisations can no longer be facilitated via the fiscal unity regime.

The Netherlands already has different reorganisation facilities in place providing the possibility of tax neutral reorganisation (e.g., tax neutral business mergers, mergers, and de-mergers). New tax facilities may have to be introduced to facilitate business driven reorganisations in case a new system will be implemented. Due to complexity, the implementation of a new regime is estimated to take at least four more years.

Jurgen van Hattum

Partner, Grant Thornton

E: jurgen.van.hattum@nl.gt.com

Victor Kloosterman

Senior manager, Grant Thornton

E: victor.kloosterman@nl.gt.com