When ETR planning and supply chain rationalisation are combined, there is a fascinating range of issues under scrutiny by tax authorities in all countries.

Cym Lowell, of McDermott Will & Emery in the US, who will be speaking on the subject in more detail at the International Tax Review and TPWeek Global Transfer Pricing Forum in Singapore on November 28 & 29explains how taxpayers can approach the issue.

Deriving maximum cost efficiency from the supply chain is a critical operational issue for multinational enterprises (MNEs) in many regions.

MNE groups continuously seek to derive maximum cost efficiency from their design, production, distribution, servicing, administrative and other functions.

Because taxation is typically one of a group’s largest costs, supply chain structuring and restructuring processes typically include tax savings as an essential element of the overall process.

Successful supply chain rationalisations inevitably involve a rationalisation of the functions and risks performed by affiliates in the supply chain.

They also involve an increase or decrease in such functions and risks performed in each country, pertinent to the planning in question.

When a function or risk is moved from one affiliate to another, questions regarding valuation of the transferred assets or functions are likely to be raised.

Tax authorities in each country affected by supply chain rationalisation are vigilant in protecting their domestic tax base, and scrutinise transactions to determine whether the functions or risks of domestic companies are restructured in a manner consistent with arm’s-length criteria.

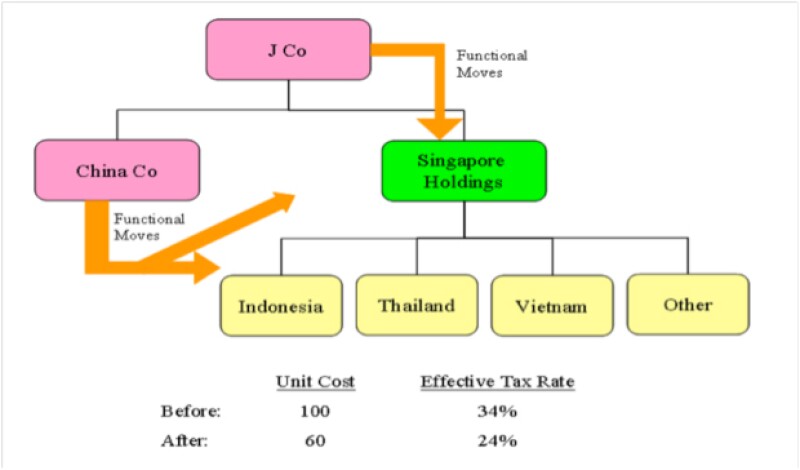

While the specific issues to be addressed depend upon the facts and circumstances of each situation, the illustration below is intended to facilitate a discussion of such points.

Case studyJCo is a Japanese parent of a group of companies engaged in the development, production, distribution and servicing of unique products. Its traditional supply chain process involves unique products being produced entirely in its Chinese factories, then sold to affiliates around the world for distribution and servicing. The competitive situation for unique products is intense, with JCo having many global competitors.

Because China can be a high-cost country, JCo is considering moving production of all component parts of unique products to Southeast Asia countries outside of China. JCo has inquired about the valuation, financial accounting, transfer pricing and potential tax authority controversy matters relating to its evolving plans.

At the present time, the supply chain process of unique products is as follows, including an overall comparison to JCo’s competitors, which have already undertaken material steps to decentralise their supply chains to drive costs out of their systems and perform critical functions in low-tax countries:

| Function |

Performed In |

Effective Tax Rate (ETR)* |

Problem/Opportunity |

JCo Current |

|||

Design |

Japan |

41% |

High op costs |

Procurement/logistics |

Japan |

41% |

High op costs |

Parts production |

China |

25% |

Increasing op costs |

Final assembly |

China |

25% |

High op costs |

Sale to customers |

Japan |

41% average |

High op costs |

Central services |

Japan |

41% |

High op costs |

Overall: |

36% |

High op costs, increasing unit cost: 100 |

|

Competitors’ Composite |

|||

Overall: |

– |

22% |

Low op costs and ETR unit cost: 60 |

Competitive disadvantage |

– |

14% |

40 per unit |

JCo Plan |

|||

Design |

Japan |

41% |

High op costs |

Procurement/logistics |

Singapore |

17% |

Fair op costs |

Parts production |

Indonesia/Other |

10% |

Low op costs |

Final production |

China |

25% |

Increasing op costs |

Sale to customers |

Singapore |

17% |

Fair op costs |

Central services |

Singapore |

17% |

Fair op costs |

Overall: |

26% |

Lower op costs and ETR, more to do |

|

The supply chain restructuring, at a minimum, should reduce the unit cost disadvantage.

In the context of the illustration, the following functions or risks have been transferred:

Procurement |

Function/risk from Japan to Singapore |

Parts production |

Function/risk from China to Indonesia/Other |

Final production |

Function/risk remain in China |

Sales |

Function/risk from Japan to Singapore |

Central services |

Function/risk from Japan to Singapore |

Issues to be addressed

· Valuation of the assets (including soft assts), functions, risks or liabilities transferred, which will depend in part on the form of the restructuring transaction, for example, sale, license, assignment, contribution or otherwise (valuations can be important for tax and book purposes) ;

· The financial accounting implications of valuations in all pertinent countries (including impairments or change from domestic to International Financial Reporting Standards)

· Transfer pricing considerations to be received by the transferor entity, or the entity that loses the function/risk in question (the focus of tax authorities is reflected in the OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines 2010 amendments for business restructurings and proposed changes relating to intangible transfers) ;

· Documentation;

· Planning;

· Advance resolutions (unilateral or bilateral, advance pricing agreements or otherwise) in Japan, China or other countries;

· Attorney-client privilege;

· Income tax planning;

· Customs, duty or consumption taxes;

· Advance resolution of transfer pricing, income tax or other issues;

· Tax authority examination preparation and handling in each potential country; and

· Dispute resolution via domestic procedures, bilateral competent authority or domestic litigation.