Italian CFC legislation has been substantially amended by Article 4 of the Legislative Decree No. 142 of November 29 2018 (Decree). The Decree implemented EU Council Directive (EU) 2016/1164, commonly known as the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (or ATAD 1), as amended by Council Directive (EU) 2017/952 (ATAD 2 and, collectively, ATAD).

The Decree applies from the fiscal year beginning after December 31 2018.

Overview of the Italian CFC rules

The Decree reshapes Italian CFC legislation as follows:

Subjective requirements:

CFC rules apply to Italian resident persons (including individuals) and to Italian permanent establishments (PE) of non-resident persons when the Italian resident person or PE controls a foreign entity; and

foreign entities include foreign PEs of controlled non-Italian resident persons and foreign PEs of Italian persons that apply the branch exemption regime.

Objective requirements – the CFC rules target foreign entities that meet the following requirements:

are controlled by an Italian person or PE (through voting rights, contractual relationship or majority of the foreign entity's profit participation rights);

are subject to an effective tax rate lower than 50% of the effective tax rate that would apply if it were resident in Italy (considering that the Italian nominal corporate tax rate is 24%); and

generate more than one third of their revenue from the following categories of passive income:

a) interest or any other income generated by financial assets;

b) royalties or any other income generated from intellectual property (IP);

c) dividends and income from the disposal of shares;

d) income from financial leasing, insurance, banking and other financial activities; and

e) proceeds from trading goods with and supplying services to associated enterprises, adding no or little economic value.

Safe harbour rule:

CFC rules do not apply if the foreign entity carries on substantive economic activity supported by staff, equipment, assets and premises. The taxpayer may request an advance ruling from the Italian tax authorities to prove that the safe harbour rule applies.

Main differences between the Italian and ATAD 1 CFC rules

The ATAD 1 sets out two alternative approaches to taxing CFCs:

1) The transactional approach (Article 7(2)(a)); and

2) The entity approach, or jurisdictional approach, (Article 7(2)(b)).

Under the transactional approach, only the CFC's passive income is subject to taxation in the hands of the parent unless the CFC carries on substantive economic activity supported by staff, equipment, assets and premises. However, a member state may opt not to treat an entity or PE as a tax transparent CFC if one third or less of the foreign entity's income qualifies as passive income (passive income test).

Conversely, under the entity approach, the controlling entity must include in its tax base all the CFC's non-distributed income if the CFC is regarded as a non-genuine arrangement.

In light of the above, the Italian CFC rules appear to arise from the ATAD 1's entity approach, because all the CFC's income is subject to taxation in the hands of the parent. Nevertheless, one of the requirements of the Italian CFC rules (i.e. more than one third of the CFC's income qualifies as "passive") arises from the optional safe harbour rule applicable under the transactional approach. In addition, the safe harbour rule provided by the Decree (based on the substantive economic activity of the CFC) is the same as that provided by the transactional approach.

Some takeaways

Effective tax rate test

A taxpayer must determine whether a foreign entity's effective tax rate is less than 50% of the virtual domestic effective tax rate (i.e. the effective tax rate that would apply if the foreign entity were resident in Italy). The latter is defined as the ratio between:

i) Italian corporate income tax that would be due on the foreign entity's income, by applying Italian corporate tax rules and the nominal tax rate (24%) to the foreign entity's profit before tax recorded on its profit and loss (P&L); and

ii) Profit before tax recorded on the foreign entity's P&L.

Under the Decree, the Italian tax authority will issue a regulation setting out operational criteria to determine the foreign entity's effective tax rate and the virtual domestic effective tax rate, including "the irrelevance of timing tax adjustments".

Timing tax adjustments should entail (among other things):

Depreciation and amortisation of assets;

Bad debt provisions;

Limitations on interest deduction; and

Proceeds taxable on a cash basis, such as dividends.

The irrelevance of timing tax adjustments can positively influence the effective tax rate test towards avoiding CFC treatment, because the Italian timing restrictive tax rules are more frequent than those typically applicable in tax friendly jurisdictions.

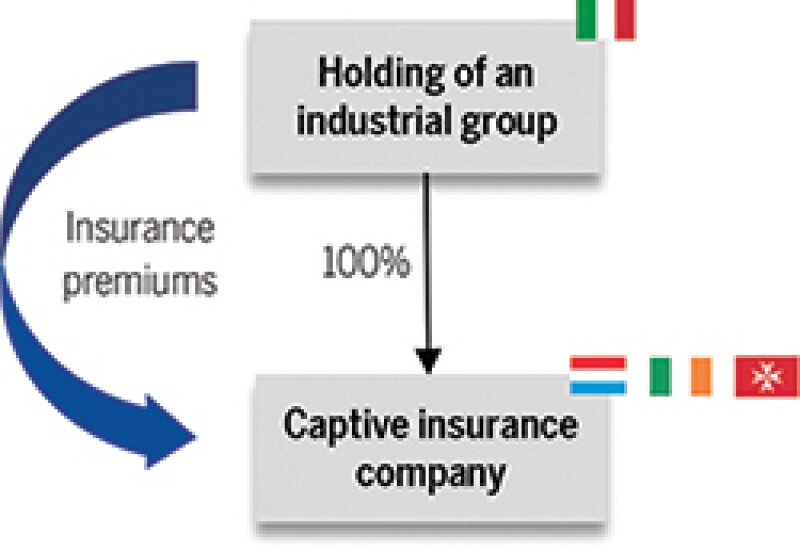

The following example, regarding a foreign controlled company involved in a 'captive' insurance business within a multinational industrial group, can better explain this concept.

Indeed, Italy provides stringent rules for the deduction of compulsory technical reserves of insurance companies (that ordinarily lead to corresponding timing tax adjustments), whereas the jurisdictions where 'captive' insurance companies are usually incorporated (e.g. Luxembourg, Ireland and Malta) generally do not provide such limitations.

Figure 1

Therefore, in Figure 1 above, if timing tax adjustments (deriving from the Italian rules on the deduction of technical reserves) had been taken into account to determine the domestic virtual effective tax rate, foreign 'captive' insurance companies would likely have fallen within the scope of Italian CFC rules, considering also that – due to their very nature – they generate passive income and require no significant physical presence in their place of incorporation.

Passive income test

Passive income includes proceeds from trading goods with and supplying services to associated enterprises, adding little or no economic value.

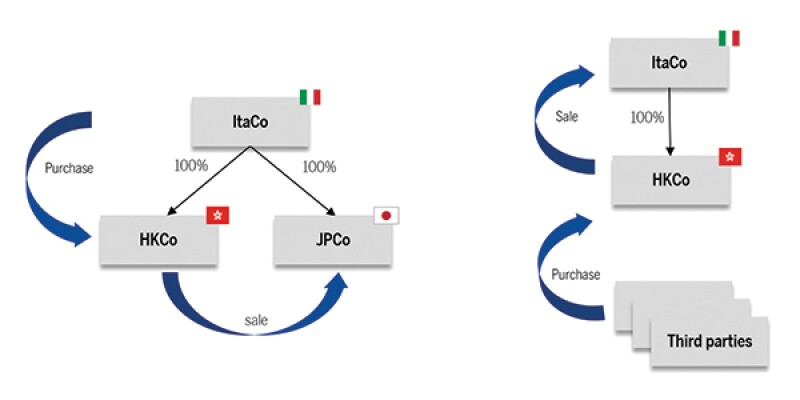

Based on the wording of the ATAD 1, only "invoicing companies" (i.e. companies that purchase from and sell to their affiliates) should fall under the scope of the provision, whereas "trading companies" (i.e. companies that purchase from third parties and sell to group affiliates or the opposite) should not generate passive income (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Moreover, the Decree refers to companies trading goods with and supplying services to associated enterprises that "add no or little economic value".

This circumstance must be assessed based on Italian (and, reasonably, OECD) transfer pricing regulations that contain a definition of the following "low value-adding services":

Auxiliary services;

Services that are not part of the multinational entity's core business;

Services that need no intangible asset and do not contribute to their creation; and

Services that do not involve an assumption or control of a significant risk by, or give rise to significant risks for, the service provider.

This guidance must also be applied to identify the low (or no) value-adding trading activities.

However, it appears that the above criteria do not completely remove uncertainty, due to the subjective evaluations that they imply.

Indeed, sometimes it could be disputable whether a service or activity can be deemed "auxiliary", "non-core" or "non-risk bearing". In other words, services or activities may or may not be deemed low value-adding depending on the specific context and circumstances, as illustrated in the following example.

An Italian company (ItaCo) controls a Hong Kong trading company (HKCo) that:

a) purchases raw materials from a group affiliate (other than ItaCo);

b) performs a standard quality check on the raw materials; and

c) sells the raw materials to ItaCo.

Under these facts, it could be reasonably concluded that HKCo performs a low value-adding activity.

Nevertheless, the conclusion may be different if:

i) ItaCo's final customers demand the highest standards of quality;

ii) HKCo is requested by ItaCo to perform a very accurate quality check on the raw materials, according to the best practice; and

iii) HKCo's personnel need special expertise, skills and training to perform the above quality check.

In any case, where the CFC effectively adds no or little economic value, it should achieve little remuneration based on transfer pricing principles and, therefore, the income to be taxed in the hands of the Italian controlling entity according to the CFC rules should not be significant.

Safe harbour rule

Italian resident shareholders may apply for a tax ruling to seek the non-application of the CFC rules if they can prove that the CFC carries out a substantial economic activity supported by staff, equipment, assets and premises (the Decree does not specify whether all these elements are required).

Therefore, a foreign entity that generates income mainly from interest, royalties or dividends may apply the safe harbour rules if it can prove that it has sufficient substance (staff, equipment, assets and premises) to carry on its business.

Conversely, it remains somewhat unclear what the effective difference is between the above safe harbour rule and that applicable before the Decree was enacted (based on the notion of a "wholly artificial arrangement"). In fact, the 'new' safe harbour rule focuses on the economic activity carried out by the CFC, whereas according to the 'old' safe harbour rule (repealed by the Decree), the CFC rules could be disapplied by proving that the non-resident company was not an artificial arrangement designed solely to obtain an undue tax benefit.

In this context, difficulties can arise in applying these criteria to holding companies because their business generally requires no significant physical presence in their country of incorporation. This issue is rather significant given that these entities typically generate 'passive' income and, as such, are targeted by CFC rules.

In further detail, assessing the 'substance' of holding companies – in terms of a factual analysis of whether they carry out an effective economic activity – can be extremely delicate for mere holding companies because they are typically not adequately supported by staff, equipment, assets and premises, due to their very nature.

The application of CFC rules could also be critical for holding companies that carry out commercial activities, because it is unclear whether the safe harbour rule needs to consider the overall business (including the commercial activities) or only the holding company's non-commercial activities.

That said, given the peculiar nature of holding companies, it seems more reasonable to assess the substance of each company based on different elements such as: (a) whether the company's key individuals possess adequate professional skills for the complexities of the business carried on, and (b) whether the company is truly involved in the decision-making process for its investments.

Andrea Silvestri |

|

|---|---|

|

Partner BonelliErede Tel: +39 02 771131 Andrea Silvestri is the coordinator of the tax practice and the team leader of the tax litigation focus team at international law firm BonelliErede. He specialises in tax law, national and international tax advice and litigation (with a particular focus on corporate taxation, acquisitions and reorganisations and financial transactions) and tax proceedings, including before the Italian Supreme Court. He is a professor of international business and taxation at the LUISS Guido Carli University of Rome Business School. |

Paolo Ronca |

|

|---|---|

|

Associate BonelliErede Tel: +39 02 771131 Paolo Ronca is an associate at international law firm BonelliErede. He specialises in tax law, with particular expertise in tax aspects of mergers and acquisitions, international tax planning, company reorganisations and private equity transactions. |